Your donation will support the student journalists of Northern Kentucky University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

The John Basalyga story

How Queens, the "Little Rascals", and hockey shaped a champion soccer coach

February 7, 2017

John Basalyga sits in his office looking out at the NKU soccer field. Three college students are playing down on the field. Basalyga is displeased by this.

“They aren’t really soccer players,” Basalyga said. “I’m always having to chase them off the field. I’m the bad cop.”

Basalyga isn’t the bad cop any longer though. He announced his retirement from NKU on Dec. 6.

“After 43 years of teaching and coaching, it was kind of neat waking up this morning and knowing I don’t have to be anywhere,” John Basalyga said. “I’ll probably be bored in about a month.”

He sits back in his chair and grabs a baseball that has been sitting on his desk. He begins to toss it up and down to himself.

“You know for a lot of the years I was coaching, I played on a traveling baseball team,” Basalyga said. “Our team made it to the championship game in Battle Creek, Michigan when my daughter was a month old. A lot of people thought it was crazy to bring a baby to a game with 85 degree heat, but we did it.”

Between the traveling baseball and caring for his three children, Basalyga won an NCAA Division II National Championship at NKU in 2010. His final record at NKU after 14 seasons was 161-88-38.

He coached players like Major League Baseball standout Jim Leyritz and US Women’s Soccer National Team star Heather Mitts.

“In 43 years of coaching, I can say I did it my way,” Basalyga said.

A family shaped by coaching

Basalyga’s wife Linda cried when he told her he was retiring.

His two grown daughters Lindsay and Courtney came over to his house Thanksgiving morning and were told then. Both of them also cried. Their entire lives had been shaped by Basalyga’s coaching career.

“Sports and my dad’s coaching career has always been a big part of our family,” Lindsay said. “We as a family have been invested in Northern Kentucky and invested in his program and the players he has coached. Knowing that chapter of his life and our life as a family was coming to a close was pretty emotional.”

While they were upset, no one tried to talk him out of his decision.

“I told them now that I will be losing money, I won’t be picking up the bill quite as much as I used to,” Basalyga said with a chuckle.

Basalyga spent more time with other people’s kids through his coaching and teaching career than he spent with his own. Every day when Basalyga would get home from teaching and coaching, he and his three kids would go out in the backyard and play. It was their bonding time away from coaching.

“For 43 years I have put my kids to the back burner. I don’t think people out there in the real world understand what coaches do,” Basalyga said. “When I got home from work at 7, 7:30 at night, I went outside for the next 45 minutes. They stopped their school work and went out in the backyard and played with them every day.”

Because of this, Lindsay, who played college soccer at powerhouse Maryland, always felt like her dad was around, even when she went to college.

“I don’t remember ever feeling like my dad was never around,” Lindsay said. “When I was in college, he would leave after a Saturday night high school game, drive through the night get down to Clemson or Wake Forest, sleep in the car, watch my game, get back in the car, slept for a few hours and go to teach.

“When I went to college that was one of my fears was my mom and dad not being able to see me play and they were at more games than some of my teammates whose parents lived 2 hours away.”

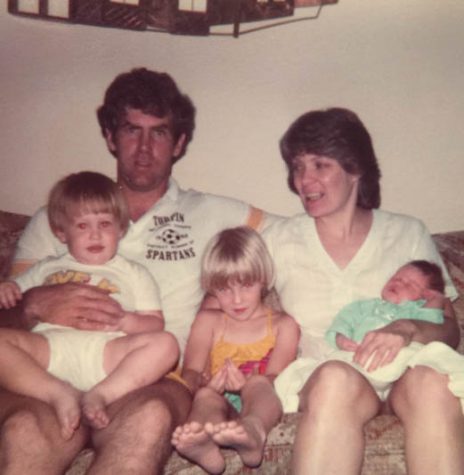

Basalyga sits with his wife Linda and three kids, Ryan, Lindsay and Courtney

Soccer created a bond between Basalyga and his oldest daughter. Lindsay once slept outside the bathroom door when she was seven so her father would take her to preseason practice at Turpin.

“I was mad at him for leaving me the day before and not taking me with him to soccer practice,” Lindsay said. “From that morning on I went to every single practice with him from the age of seven through twelve to preseason practice. I was with him all day during the preseason and I would train with his players sometimes. I had a unique bond with him that was all built around the game of soccer.”

Lindsay would join in on practices from time to time and her father would watch her play just as hard as the high schooler boys she was playing against.

“My guys would throw her in puddles and just abuse her,” Basalyga said.

Linda and her three children sat in the stands with the parents. Basalyga said she was the best PR person he has ever had. She kept the parents from turning on him.

“There were times where the parents were incredible and they wanted to sit with my mom and meet for lunch before a game,” Lindsay said. “There were parents at Northern that she would travel with to games. She went to almost every home game my father has ever coached.”

Things weren’t always great with parents though, and there were times where parents took out their frustrations on Basalyga’s family in the stands.

“They treated my mom poorly in the stands and treated my brother and sister poorly because they felt their son should have been playing,” Lindsay said. “To hear parents bad mouth my dad, who is spending more time with their sons than he is with us as a family. It can be really hurtful.”

During many NKU games, Courtney would sit in the stands as close as possible to her father to hear what he was saying and see what he was doing.

“She would say ‘I just came down here to listen to you yell at the refs. Some of the stuff that came out of your mouth just made me laugh,’” Basalyga said.

After every game, the family would go out and have dinner together after games. When his teams lost, the whole family had a mourning period.

“I’m going to miss my family being at my games,” Basalyga said.

Finding his way on the streets

In the late 1950s, in the projects of Queens, New York, a young John Basalyga played football without pads, baseball and hockey. They kept him out of trouble in the cold, black, concrete jungle.

He went to high school where, Basalyga says, girls were arrested for prostitution and where students carried razor blades in their hair. He walked through race riots in 1967.

“It was challenging. I saw some crazy things,” Basalyga said. “I wouldn’t change my childhood. I learned more in the streets of how to take care of myself that had more life skills than we could teach our kids these days.”

Both of Basalyga’s parents and brother were alcoholics. His father and brothers were World War II and Vietnam veterans. Basalyga didn’t drink in high school or college. The first time he was ever drunk was at age 24, the night before his wedding.

“I was the only one in my family that wasn’t chemically dependant,” Basalyga said. “I had this dumbass view that athletes didn’t do that. When my brothers turned 18 my father took them to get drunk. When I turned 18, my dad gave me a new baseball glove because he knew I didn’t drink.”

The film “Little Rascals” inspired Basalyga. He wanted to do everything they did, like being a firefighter or having his own baseball team.

“If it wasn’t for sports and the ‘Little Rascals,’ I wouldn’t be where I am today,” Basalyga said.

Basalyga and his friend settled for starting their own roller hockey team when he was 13 years old. They funded it on their own through raffle tickets, fundraisers, and contributions. They paid referees and bought jerseys without help from any adult.

Basalyga played against teams operated by boy’s clubs and played these teams for three years.

Eventually, tired of seeing Basalyga and his team do it on their own, the YMCA took the team into their league.

“I got kids out of the street,” Basalyga said. “We had a blast. We were just a bunch of little rascals out there. I took pride in coaching that team.”

When Basalyga and his friend arrived at the YMCA for their first coach’s meeting, the man running the league thought they were there for a different reason. He was shocked to learn they were coaches.

“We asked him if there was a meeting for a hockey league that night,” Basalyga said. “And he said ‘yes. Do you have an adult with you?’ We told him no. But they let us in.”

Twenty five other coaches sat in the room, all of them grown men.

The First Taste of Soccer

Baseball was the sport Basalyga excelled at the most. During his career he tried out for multiple MLB teams including the Yankees, Cardinals, and Mets. He played in college as well, first at a junior college in New York, and then at Bowling Green State University.

During his time in junior college, Basalyga was trying to find a way to stay in shape after the baseball season ended and before his hockey season began. His coach at the time was also the cross country coach, and Basalyga thought that would be a good way to accomplish this goal.

“His warm up was run four miles. I hadn’t run four miles in my damn life,” Basalyga said.

He didn’t last a day.

A few days after his cross country experiment ended, he, his baseball coach and the soccer coach Jim Megly were having dinner at a small table. Knowing the predicament he was in, Megly offered to take him to practice to stay in shape and to be the practice goalie, since the roster at the time only carried one goalie.

Basalyga excelled, using his skills he had as a shortstop in his primary sport to react to the shots of the members of the team. He was like a bowling ball, running into potential scorers and knocking away any shot that came his way.

“Getting hit didn’t bother me,” Basalyga said.

After practice, the team was supposed to leave for a road trip. As Basalyga was leaving practice, the coach stopped him and asked if he wanted to come on the road trip.

“I told him I wasn’t on the team,” Basalyga said. “He told me he would grab me a jersey and let me play.”

Sure enough, Basalyga made the trip that day. Three games later he was the starting goalie.

‘I Hated School’

Basalyga hated school as a kid. He barely graduated from high school and was on academic probation much of his junior college career and had a 2.0 GPA his junior year at Bowling Green State University.

It was his senior year when he finally made the Dean’s List with a 3.5 GPA.

“When I finally made the Dean’s List my mom thought I was on ‘his list,’” Basalyga said. “I told her that that was actually pretty damn good.”

At Bowling Green, Basalyga started as a business major. One day, his baseball coach asked him if he would ever be interested in coaching. He had coached when he was 13, naturally he’d want to again.

“He told me I should change my major to education,” Basalyga said. “I told him I hate school and you want me to do what?

“He said ‘if you were a coach you would be there with the kids and you can coach and it would be perfect. If you stick with business you would have to find time to do the coaching you want to do.’”

Baslayga coaches up his team after a game at the NKU Soccer Stadium.

He took his coach’s advice and changed his major.

He stunned all his former teachers when he went back to his high school to do his observations.“They were like ‘What? You gotta be kidding me. You hate school,’” Basalyga said. “I said, ‘what better person to teach than someone who doesn’t like school?’”

He was hired by Turpin High School in Cincinnati in 1973 to teach business and physical education and taught for 35 years.

“Kids were afraid of me,” Basalyga said. “In 35 years of teaching, I only sent four kids to the office. My bark was much worse than my bite.”

One of those four kids was a guy named Rodney. Rodney fought another student in Basalyga’s first period class in the late 1980s. Basalyga was forced to send him to the office.

Basalyga struck up a relationship with Rodney though, despite Rodney’s tardiness to class. Basalyga wouldn’t send him to the office, but he wasn’t as lucky with his other teachers. He was summoned to the dean of attendance for skipping too many classes, some of them in the middle of the school day.

“I said ‘you’re busted’ and he said I know,” Basalyga said. “I said when you go down to the office, don’t try to argue with them, throw yourself to the mercy of the court. When he asks you, just tell them you had Gold Star or Skyline the day before and you had the squirts and you were in the bathroom.”

Rodney came back 20 minutes later with a week of detention

“‘It was suppose to be two but he loved my excuse,’” Basalyga recalls him saying.

About two weeks later Rodney was tardy again, but this time he came with a note.

“He had a note that said ‘Please excuse Rodney, he had Gold Star chili last night and had the squirts. Signed Rodney’s mother’. I said that’s not your mom,” Basalyga chuckled. “He was just a kid who had a rough life.”

Rodney did graduate from high school and joined the 101st Airborne in the Gulf War. He came to visit Basalyga in his classroom before he left, and told Basalyga when he came back he would come into class and have pizza.

“A year and a half later he walk in in front of the whole class in uniform, sits down and says ‘You guys can continue what you are doing’ and plops down a pizza,” Basalyga said.

A few years later Rodney arrived at Basalyga’s house an a repairman and the two discussed his high school days.

“He said ‘I had so much damn trouble in school but you were the only one I knew I could go to and you could understand where I was coming from,’” Basalyga said. “I said that’s because I grew up in the streets and I know you guys need a break sometimes.

“Just like I did.”

John Basalyga moments after winning the 2010 NCAA DII National Championship

The John Basalyga story: Part Two

Becoming a Soccer Coach

Basalyga sat in his office in 1979. He was also the quarterback coach for the Turpin football team and the baseball coach at the time.

The phone rang in his office and at the other end of the line he hears the voice of the athletic director.

“He says to me ‘It says here on your resume that you played soccer in college,’” Basalyga said. “I just started laughing. I told him, ‘I don’t know what the hell that is. I just played goalie, I was a piñata.’”

The athletic director proceeded to tell Basalyga that the soccer coach at the time had quit and asked Basalyga to become the next head coach.

“I told him I didn’t know anything,” Basalyga said. “He told me ‘John, I need you to take this program over.’ So I did.”

In his first weeks as coach, he coached as if they were a hockey team; physical play and mental toughness were placed at the core of his coaching regime. In his first few games, Basalyga substituted players after every goal, much like hockey teams do.

“I didn’t know what the hell I was doing,” Basalyga said. “My kids were like ‘this isn’t hockey. You don’t change lines after you score.’”

Basalyga struggled for two years trying to coach soccer like a hockey team. He started reading books.

“My daughter was two and three. I would read a book, watch some videos, and then teach her what I was reading. She was my guinea pig,” Basalyga said.

Lindsay remembered her dad going to coaching conventions and loved when he would back new equipment for she and her siblings to try out.

Basalyga turned those days into a 325-93-58 record at Turpin High School, including three Ohio state championships in 1986, 2000 and 2001. During this period, he was also coaching ice hockey in the winter at Moeller, coaching baseball in the spring and coaching his children’s teams.

Building a college program

Basalyga originally applied to NKU to become the head coach of the women’s soccer team in 1997. Jane Meier, former athletic director at NKU, instead hired another Cincinnati high school coach, Bob Sheehan, to run the women’s soccer program.

Meier didn’t forget about the Turpin head coach though, and when the men’s head coaching position opened up in 2003, she knew just who she wanted to lead the team.

“I remembered John from that interview and hoped he would apply and even if he hadn’t applied I was going to reach out to him anyway,” Meier said. “He had so much success when he was at Turpin. The kids really liked him, at least in the interview.”

We were pretty fortunate at NKU to get someone of John’s quality, even though he came from the high school ranks. He knew what he was doing.”

Basalyga talks with his 2016 Norse team after a victory.

Basalyga said he owes his career to Meier.

“Jane Meier saw something in me. My whole coaching career is baseball and Jane Meier pulling me out of the fire,” Basalyga said. “She let me go. She let me do my thing. Without Jane, I wouldn’t be here.”

In his first season as head coach, the Norse went 4-9-3 on the season, and some players started grumbling about how hard Basalyga was pushing them.

“When he first started coaching them there was some grumbling because John’s intense and he pushed them and he was taking them to another level to be competitive,” Meier said. “That was the only time I ever had any grumblings about his style.”

It was the only losing season in Basalyga’s DII career. The Norse went 12-6-2 the next year, and the grumbling ceased, from what Meier could tell. In 2006, the Norse went 16-3-3 and were Great Lakes Region champions.

Basalyga’s teams continued to improve after each season, but needed something more to get to where Basalyga dreamed.

“He recruited players he knew he could coach. He was smart and knew what he needed each year,” Meier said. “He makes the decision to recruit internationally because he knew he needed another level of player that wasn’t going to come to NKU from the United States.”

Enter Steven Beattie, a talented, goal scoring forward from Dublin, Ireland, who would later be drafted by Toronto F.C. and now plays professionally for Cork City F.C. in Ireland.

Beattie first met Basalyga in Memphis, when the coach came marching across the field after Beattie’s Irish team finished playing in a showcase.

“He came marching across the field and said ‘Dude I want you on my team,’” Beattie said. “I was like, ‘who’s this guy?’”

Even still, Beattie and Basalyga connected quickly, and the Dublin native committed to NKU and arrived on campus in 2007.

Beattie compares his first practice with Basalyga to the scene in the movie “Miracle”, where the 1980 US National hockey team is speed skating back and forth and the Kurt Russell version of Herb Brooks repeated tells his team to get “on the line”.

The Norse, however, were practicing outside in the blistering summer heat.

“We were down on the field and cleats were pretty much melted to the turf and Bas just ran us into the ground,” Beattie said. “I was thinking ‘what am I doing? This is madness.’ But the way we trained the first day was the way I was trained for four years. He just makes you a better player and an overall better person.”

Basalyga’s intensity was the same during practice as he was in games.

“I dared kids to quit,” Basalyga said.

This was directed towards the referees as well, and those interactions were tense at times.

“One time the referee told him to shut up. So he (Basalyga) taped up his mouth so he couldn’t talk in the middle of the game,” Beattie said.

When the team made the transition to DI in 2011, Basalyga made his team play for an hour and 20 minutes straight. One team was winning by two goals. At the 45 minute mark Basalyga told his team that the next goal would win. The team played another 45 minutes.

“At the end the losers were running,” Basalyga said. “The kids got tired and I kept them playing.”

That practice happened on a Tuesday. The next game was on Friday. The Norse played Stetson and were getting beat in the first half. In the 88th minute though, the Norse scored to tie the game to send the game to overtime.

“We go into overtime and they (Stetson) couldn’t get past midfield because they hadn’t played that long before,” Basalyga said. They were so tired they couldn’t even kick the ball.”

The Norse scored in double overtime to seal the comeback victory.

“I went to the kids after the game and said ‘Where do you think we won that game?’” Basalyga said. “They said ‘because on Tuesday we played longer.’ I told them that’s why I did that to them.”

The National Championship

In 2010, the Norse exploded once again, recording a 20-2-3 record on the season, vaulting them to the DII National championship game in November.

RELATED: Norse soccer wins National Championship

In the weeks leading up to the national championship, Basalyga banned the team from wearing long sleeves, pants, or any warm weather gear despite brutal cold, snow, and ice.

“I thought he was crazy at the time,” Beattie said. “Guys weren’t allowed to wear gloves or hats. What I learned after we won and as I get older, he prepared us for the day of the national championship game which was snow in Louisville.”

The Norse celebrate on the field in Louisville after winning the National Championship

In fact, the snow was so bad the day of the national championship kickoff was delayed for over an hour to clear snow off the field. Rollins College, the Norse opponent, was a Florida team and never had to play in the snow prior to this game.

“We had pretty much already mentally been there training like that for three or four weeks,” Beattie said. “(Rollins) was from Florida and their goal keeper was wearing a wooly hat for the national championship game.”

The Norse took the field the same way they had been practicing for weeks; short sleeves and shorts.

“People were like this guy is crazy, this NKU coach is crazy,” Beattie said. “There is method to his madness, you don’t even feel the cold. The other guys come out for warmups with big jackets and tights on and everything else. Everything he did he had a plan.

“Obviously at the time you can’t see it, but when you look at the results his plans were just perfect. There was a method to his madness, and a lot of times it was madness believe me.”

Basalyga’s madness resulted in a 3-2 victory over Rollins to collect the 2010 DII National Championship, something Beattie told his coach the first week on campus they would accomplish.

“My first weekend at NKU we were talking and I said ‘coach we are going to win a national championship’ and we had a laugh,” Beattie said. “On the field in Louisville I said ‘I told you we would win that’ and he said ‘I never forgot you told me that. I believed you at the time but I didn’t want to show it.”

Basalyga, according to his daughter, is goofy and lovable away from the soccer field

The John Basalyga story: part 3

Never too far away to help

On the field Basalyga’s passion and competitiveness were ever present, but if you were lucky enough to get to know him off the field you would meet a slightly different character.

“He’s goofy. He is weird as sin. He’s extremely playful. He says I love you all the time, he’s a hugger,” Lindsay said. “My teammates from college were like ‘OMG I miss getting hugs from your dad’ and people that don’t know him only see who he is on the sideline. He’s not a cold standoffish person but you gotta earn that relationship.

“He would do anything for any player or anyone who earned that right to know my dad and have that relationship.”

When Lindsay was in Maryland, the closet in her apartment totally collapsed. There were clothes and school items all over the floor.

“My dad got in the car in between training sessions and drove eight hours all the way to Maryland to rig my closet back up with athletic tape,” Lindsay said. “He always use to fix stuff with athletic tape and rope. He was that much of a handyman that the athletic tape would fix anything.”

Athletic tape was used to fix everything, including Lindsay and her siblings’ toys when they were younger. It didn’t fail this time either, holding the closet up for the two years Lindsay lived in that apartment.

Beattie describes Basalyga as a father away from home. He was the first person Beattie called after he was selected by Toronto FC in MLS Draft. He called Basalyga for advice on every professional decision.

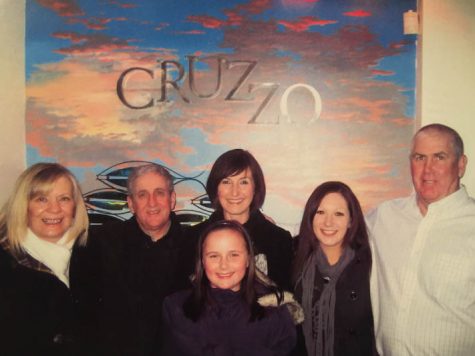

Linda (far left) and Basalyga (far right) stand with Steven Beattie’s family during their trip to Ireland

“He’s got the best advice you could ever get,” Beattie said. “I called him about contracts, about money, the teams I should go to. He talked me through everything. We still have the same relationship we had when I walked into college in 2007.”

When Beattie tore his ACL in his first game for the Puerto Rico Islanders, Basalyga was ready to fly down and to see his former player.

“That’s the kind of guy he was,” Beattie said. “He was prepared to drop everything to come see me even though I wasn’t part of the program.”

Other former players have been affected by Basalyga so much, they formed an indoor soccer team in his honor.

“There are a group of guys who played at Northern back when my dad got there and they have a group of NKU alumni who are playing in an indoor league together and named the team ‘John Basalyga’, but completely botched the spelling,” Lindsay said. “Those are the types of relationships he had and not everyone earned that. Players need to earn the right to know you beyond the surface of just being a coach.”

Retired, but not finished

Basalyga doesn’t have any hobbies. He believes he will probably be bored in retirement.

“My hobby is kids,” Basalyga said.

Basalyga now hopes to start a baseball or soccer academy with Lindsay in the future, so he won’t be completely out of his game.

“We have a guy who just came out of the woodwork last month who wrote a letter to my dad and is now helping my dad set up his own business,” Lindsay said.

Lindsay and her father are hoping to start this summer with a couple area high school teams and grow from there.

Basalyga knows it’s time to move on. He wants to spend more time with his wife and kids. He could have retired before the transition to Division I, but told Meier he thought he was the right guy for the job.

“I could have walked away before the transition on a high,” Basalyga said. “I can take a hit on my record. I wanted to move the program in a direction that is going to allow the next guy to have some sort of momentum.”