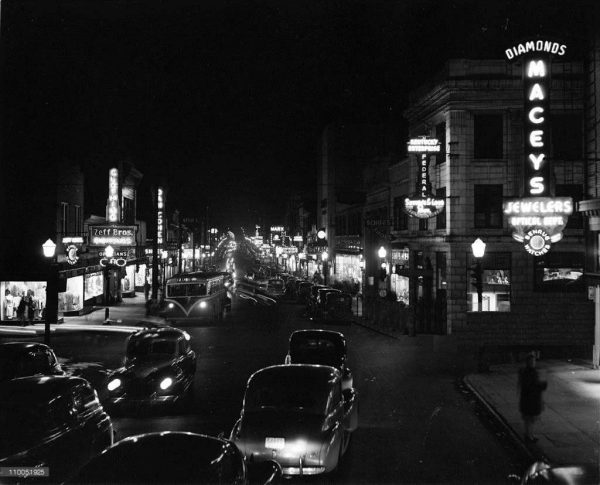

In the 1950s Golden Age, a cruise down Monmouth Street in the center of Newport seemed to be the epitome of glamor: There were flashy lights, A-list performers, gourmet cuisines and spotless streets.

But there were also vicious murders, shady mobsters and a bounty of illegal activities.

Frank Sinatra would grace the Cincinnati Music Hall, then make his way across the river for a little backroom gambling. Dean Martin actually worked as a blackjack dealer at one of the finest clubs of the time, which Marilyn Monroe also visited.

Even President John F. Kennedy took a trip to Newport… but not for the same reasons.

The “Sin City” of this age was known across the nation, and it certainly had earned its reputation.

Vices introduced to Newport

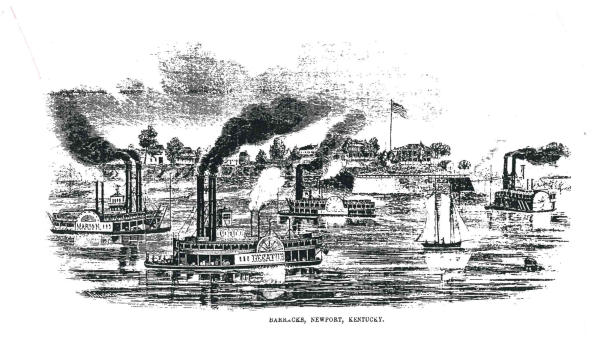

The city itself was founded in 1795 by General James Taylor, an early settler. Taylor was given the northern Kentucky land for his military service in the Revolutionary War.

From this point on, Newport became a crucial military location. The Newport Barracks were constructed in the 1800s and served many purposes throughout the War of 1812 and eventually the Civil War, including being a prison for enemy troops, a recruitment location and a hospital.

By the 1880s, the barracks had become the headquarters for the southern department of the United States Army.

And this was when the vices came to Newport, according to City Historian Scott Clark.

“You have a group of men that are looking for diversions from army life,” Clark said. “It didn’t take very long before houses of prostitution and illegal gambling were happening around the Newport Barracks.”

This immorality only amplified when Prohibition took place in 1920, making the production, transportation and sale of alcohol illegal.

Peter Bronson has spent much of his later life researching and writing books about the history of the Greater Cincinnati region. In his book about the Sin City era, “Forbidden Fruit: Sin City’s Underworld and the Supper Club Inferno,” Bronson explored the impact of Prohibition.

“When Prohibition came along, this group of organized criminals decided they could fill a huge demand for bootleg liquor,” Bronson explained.

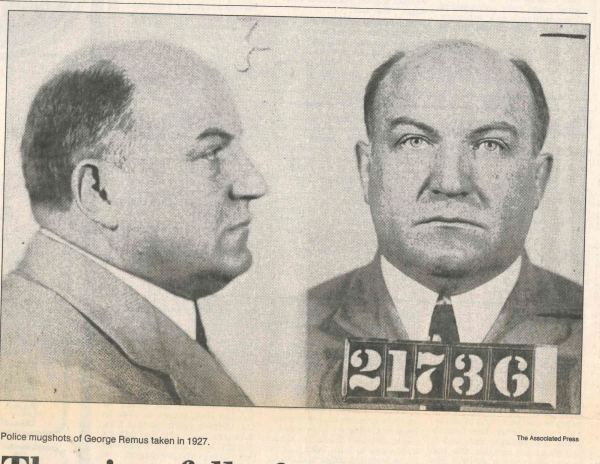

One of the most successful illegal distributors in the country set up shop in Greater Cincinnati. Known as the “King of the Bootleggers,” George Remus purchased distilleries in Northern Kentucky and was able to get by under the guise that he was producing alcohol for “medicinal purposes.” In reality, Remus would have his own men hijack delivery trucks and bring back large amounts of whiskey for him to sell on the black market.

“[Remus] had it set up so that he pretty much owned everybody,” Bronson said. “He had the police, the sheriff, the judges, the prosecutors, the politicians, the council members. Everybody was on the take with George Remus.”

Eventually, federal agents had enough evidence to prosecute the bootleg king for violating the law. When Remus went to prison, the gangsters who worked for him returned to Newport and set up casinos and nightclubs, Bronson said.

In 1933, Prohibition was repealed and the flow of alcohol returned.

The question then became, how could bootleggers and gangsters now make their money?

“Many of the bootleggers just segue-way themselves right into the gambling business,” said Northern Kentucky University History Professor Dr. Paul Tenkotte.

Business boom: Casinos, clubs and crooks

There were two types of places where folks could gamble away their money: bust-out joints and carpet joints.

Bust-out joints were not owned by the mob, and they were certainly not as charming as the mob-run locations. Bust-out joints were “tacky, rough places” that were almost always rigged in favor of the house, Bronson explained.

Carpet joints, however, were much more attractive and were run by the mob. The odds were more fair and they actually had carpeted floors, rather than wood and sawdust.

As the mob began to take over the town, they would buy up clubs and turn them into carpet joints, with fine dining, show business, slot machines, roulette wheels and plenty of other illegal activity.

Mustang Betty’s, which is now an antique store on Monmouth Street, featured a brothel upstairs, drinking and gambling on the first floor and an intricate system of phone lines to take nationwide lay-off bets in the basement.

Glenn Schmidt’s Playtorium was a mob hangout with a bowling alley, bar and casino.

The Lookout House was another carpet joint one town away in Wilder. It was situated right at the top of a hill—hence the name—so that when the state police came to raid the joint, the mobsters could see them coming from miles away. By the time the police arrived, all they found were people dining at a supper club; all traces of gambling had been whisked away to a hidden room.

Bronson explained that when a grand jury would begin investigating illegal activity, the mob would simply move their operation to another location, or even another county.

“As soon as the grand jury dusted its hands off and said, ‘We’ve nothing to see here folks,’ then they would just open up again in full tilt,” Bronson said.

Gambling proved to be prosperous for the city. If a tourist won big at the casino the night before, he might just visit a local jewelry store the next day and buy an expensive diamond for his loved one. Mobsters would bring their girlfriends into the dress shops and purchase only the finest gowns.

“A lot of the citizens were enjoying a kind of economic benefit of [gambling],” Clark said.

Fact vs. fiction: Mob presence

When Bronson began conducting research for his book about the Sin City years, he figured most of the rumors about the mafia were just that—rumors. Maybe there were a few punks and some wannabe mobsters who thought they were tough.

But he found out pretty quickly this was not the case… at all.

These were the “big boys,” as the author called them, from New York, Chicago, the East Coast and, most significantly, Cleveland.

The Cleveland Four became the name for the mobsters who made their way down south to Newport when they realized what a premiere location the city was in. They built a market in Ohio and made Newport their hot spot. People from across state lines could come down to Sin City and get away with just about anything because there was no jurisdiction.

“It was the adult playground,” Bronson said.

The syndicate liked to keep things tidy, and they generally didn’t look for trouble or like to be brought to light, Tenkotte said.

But they also had their enforcers.

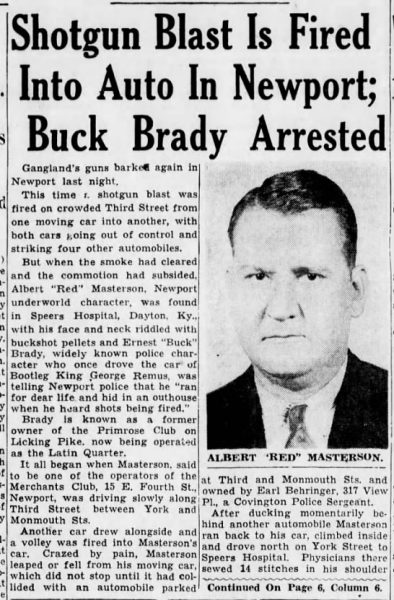

Red Masterson worked for the Cleveland Syndicate. At one point, he told a reporter he had killed more than 100 people. If someone stepped out of line or if the bookies running bust-out joints got a little too powerful, Masterson was called in.

His signature move was the “Newport Nightgown,” according to Bronson. The hit man would wrap a victim in chains and attach a concrete block for good measure. Then, he would take them out to the suspension bridge and throw them off, watching as they plummeted to their death.

“Criminal activities, murders, shootings will actually take place,” Tenkotte said. “And when juries meet, the syndicate and crime figures have very good attorneys. Everybody’s kind of on the take, and usually very little happens to them.”

The beginning of the Beverly Hills

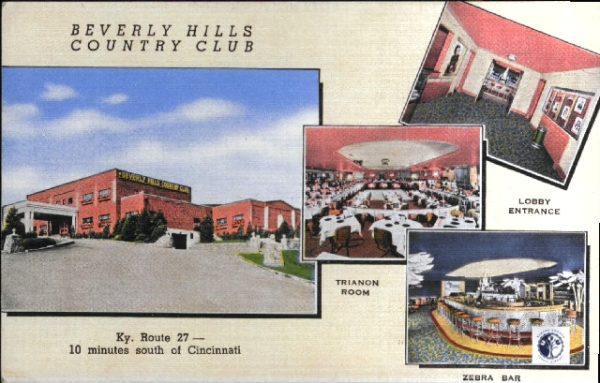

The Beverly Hills Country Club was the original name of the joint opened in the early 1930s by Pete Schmidt, a gangster and affiliate of Prohibition bootlegger Remus. Located just south of Newport in Southgate, the Beverly quickly became the “showplace of the nation,” hosting the decade’s top performers and the wealthiest clientele possible.

But the mob believed the club was theirs for the taking.

Moe Dalitz was a tough guy ring-leader for the Cleveland Syndicate in the 30s. One visit to the Beverly Hills Country Club and Dalitz decided he had to have the place.

Dalitz presented the owner, Schmidt, with an ultimatum: ‘I’ll buy you out or I’ll burn you out.’

But Schmidt was also a tough guy and refused Dalitz’s offer, hoping he would go back to Cleveland and mind his own business.

But that is not what happened. In February of 1936, the mob burned down the original club, killing the five-year-old niece of the property caretaker in the act.

“She was the first casualty in Northern Kentucky of the mob,” Bronson said.

The mob took over the location, rebuilding and creating an even more boisterous version of the Beverly Hills Club. Fitted with gigantic chandeliers and plush carpets, the club served five-star meals and provided only the best entertainment, including Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin.

The Beverly Hills Club seemed to represent everything Newport hoped to be… for a time.

Along come the Kennedys… and the smear campaign of an all-American quarterback

By the late 50s and early 60s, the Newport community had enough. For decades, they had attempted to make reform efforts, but they needed more.

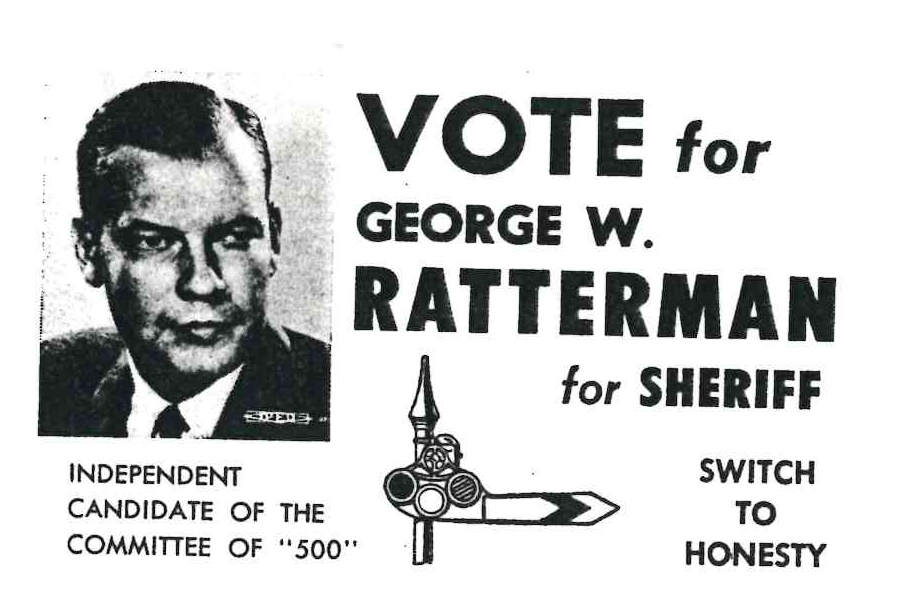

The Committee of 500 was a well-financed group of community members, mostly made up of Protestants and led by everyday citizens. They decided they needed a representative to run for Campbell County sheriff: someone Catholic, clean and likable.

So they chose George Ratterman: an all-American from Cincinnati who played football for the University of Notre Dame and later for the Cleveland Browns. After a leg injury ended his career, he earned his law degree from Salmon P. Chase College of Law and became an investment banker, as well as a father of eight.

While running for sheriff, Ratterman received an invitation from mobster and club owner Tito Carinci, who was also a former football player for Xavier University, to meet up and discuss how Carinci wanted to get out of the mob life.

At least that’s what Ratterman thought.

When the two met, alcohol began flowing and Carinci slipped chloral hydrate, also known as “knock-out drops,” into the sheriff candidate’s drink.

Before he knew it, Ratterman woke up in bed half-naked with a stripper, Juanita Hodges (her stage name was April Flowers). He was arrested for soliciting prostitution but said he had no idea how he wound up in the Newport hotel room.

At Ratterman’s trial, it was discovered that massive amounts of knock-out drops were in his bloodstream. The charges against Ratterman were dropped immediately and he won the election for sheriff.

But news of what had happened to the sheriff spread across the world. Bronson said in his research, he even found headlines from Tokyo about Ratterman.

At the same time, President John F. Kennedy had recently appointed his brother Bobby Kennedy to the role of United States attorney general. According to Bronson, Bobby Kennedy was widely criticized because he lacked experience for the job. Looking to make a name for himself, he stumbled across the story about Ratterman and found his opportunity.

“The Kennedys declared war on organized crime in Newport,” Bronson said. “Which is amazing when you think about it.”

The federal government prosecuted mobsters for violating the civil rights of Ratterman. While the trials lasted for years, the government eventually won.

Juanita Hodges, the stripper found in bed with Ratterman, was a star witness who testified against the mob.

She was found decapitated in Miami a few years later.

The efforts from both the national and local levels proved to be effective. As the years went on, most of the mafia was either put in prison or fled town.

“The mob had withdrawn, mostly, and gone to Las Vegas. You can think of Newport as sort of the first Las Vegas,” said Mark Neikirk, former NKU Scripps Howard Center director and Cincinnati Post journalist.

The deadliest inferno in Kentucky history

As more and more mobsters left town, many clubs and casinos were sold off or shuttered. One of those was the aforementioned Beverly Hills.

Richard Schilling purchased the Beverly Hills Club in the late 60s with plans to bring it back as a supper club. He also denied mob partnership, and in the process of reopening in 1970, the Beverly was burned down again.

Schilling was persistent, though, and finished out his renovations, opening the Beverly Hills Supper Club in 1971. The owner turned the dinner theatre into one of the most successful joints in the region, a premiere spot for weddings, proms and dates.

On Memorial Day in 1977, the Beverly Hills Supper Club was packed. Singer John Davidson was set to headline the night.

Two waitresses walked into the Zebra Room and saw what appeared to be light smoke. Suddenly the smoke began billowing from the room and headed upstairs. In the main Cabaret Room, a busboy came on stage and tried to warn that there was a fire. Many patrons paid no attention. Others tried to make their way toward the exits, but it was too late.

Within minutes, the fire erupted and destroyed everything in its path.

165 people died.

According to Bronson, many perished inside the building. There was an exit sign placed over a closet, and many bodies were found there. Some people wandered outside only to drop dead within moments. Others died later because of severe lung damage.

Tenkotte recalled arriving home from his high school prom and watching the events unfold on live television.

“It was just unfathomable that a tragedy of this sort would occur and that so many lives were lost,” Tenkotte said.

Bronson said as he investigated the fire, he found loads of evidence which pointed to arson.

As the fire marshal began to investigate the potential arson, the state police showed up and took over the investigation, Bronson said. While bodies were still being discovered and the flames were still going, the governor declared the fire was an accident.

In a 1979 investigation, a letter from the club owner’s mailbox was uncovered, which read, ‘You keep building, we’ll keep burning.’

Bronson said this was only the tip of the iceberg when it came to evidence that pointed to arson. To this day, investigations into what caused the fire have all been inconclusive.

A new, seedier era

When Neikirk began as a reporter for the Cincinnati Post in 1979, he got to see firsthand the remnants of the Sin City heyday.

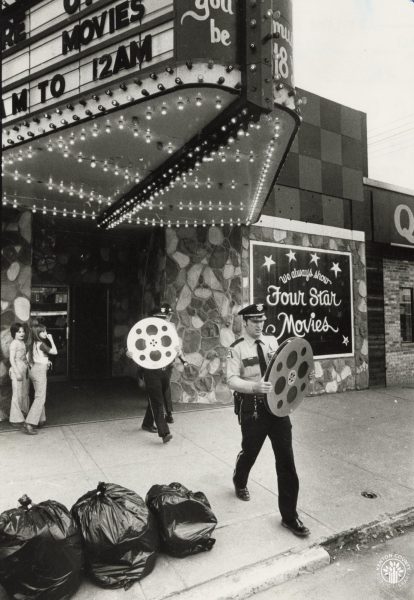

Monmouth Street was still at the center, but according to Neikirk, there was now an abundance of strip clubs and cinemas for X-rated movies.

One night, Neikirk recalled getting a tip from the state police that there would be a raid of the Cinema X. So he parked on the street across from the theater and watched as police cars zoomed onto Monmouth Street and blocked off the exits.

“They didn’t arrest too many people,” Neikirk said. “They just sort of embarrassed them.”

There was always crime on the weekend, and a lot of it was violent, the former journalist said.

“You could just assume in Covington and Newport… it’s the weekend, there will probably be a murder, and I’m going to have to cover it,” Neikirk said.

It was a challenge to determine what could and couldn’t be regulated, and the city was essentially writing the law on how to regulate things like strip clubs, Neikirk explained. Reformers were taking their concerns all the way to the federal courts, and they continued fighting to create a different legacy.

The Newport of today

The development of destinations like Newport on the Levee and the Newport Aquarium solidified the change toward making Newport more family friendly, Neikirk said.

Clark pointed out how the city has worked to marry new developments with historic preservation.

There are a few remnants of the Sin City era still lingering around. The Brass Ass is one of the only strip clubs still in business on Monmouth Street. Glenn Schmit’s Playtorium was reopened as the Newport Syndicate—a spot for proms and gatherings in the area… without the illegal backroom activity.

Decades later, people continue to be intrigued by the Sin City heyday.

“We’re just appalled, and at the same time just extremely interested,” Tenkotte said.

Clark said it’s important to tell the whole story when it comes to Newport’s past and present.

“The Newport we see today is from the actions of people that want to be able to tell our story [and] be proud of our past without hiding from it,” Clark said.