This story was written in partnership with LINK nky, Northern Kentucky University’s Advanced News Media Workshop class and The Northerner for this series on the changing face of Northern Kentucky.

Read the other stories in the series here:

- The face of Northern Kentucky: ‘It’s starting to look different’ by LINK nky’s Haley Parnell

- Breaking bread at immigrant-founded restaurants by The Northerner’s Isabella Huecker

- Five international markets share a slice of home by The Northerner’s Elita St. Clair (with video)

- Tiburcio Lince brings ‘alegría’ to Latino Student Initiatives at NKU by The Northerner’s Shae Meade

A single event in 1991 changed Mwamba Mwamba’s life forever.

“It’s not something you can just easily shake off or forget,” said the Independence resident, who now works to help the French-speaking Congolese community adjust to life in Northern Kentucky. “The student protest of Mobutu Sese Seko, the president-dictator of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, happened on the center square of the University of Kinshasa in the Congo’s capital city on a fall day.”

The protest’s leaders read prepared statements through a megaphone, protesting the dictator’s rule and the lack of free and democratic elections.

“We [were] protesting the imprisonment of the Congolese people in their own land,” said Mwamba, who was a student at the time. “We were driven by conviction as opposed to fear of death.”

Suddenly, police officers flooded onto the center square and opened fire. Bullets flew. Mwamba wondered if he would make it home.

“They were just gunning people down left and right,” Mwamba said.

The city was locked down, and public transportation was gridlocked.

Mwamba, who was 18 at the time, crawled on his belly until he got to a place where he could get up and run. For 25 miles, Mwamba traveled, winding his way through small streets and alleyways trying to make it back home.

“By God’s grace, I did make it home,” he said.

Then the secret service began apprehending anyone carrying a student ID in order to see if they were connected to the protests. Most of those students, Mwamba said, never returned home.

Growing up

Growing up in Kinshasa, Mwamba said he could have never predicted where his life would lead. In a city of over 10 million people, where everyone wanted to make it big, citizens migrated from the villages to the capital to pursue their vision of success.

Mwamba’s parents had also chased this dream, moving from the village where they grew up into the city, where Mwamba’s father got a job as a customs agent and his mother became a stay-at-home mom and home business owner, hustling and selling things to support her growing family. There were nine kids in all, four boys and five girls. One of Mwamba’s brothers died young, leaving a 10-person family.

A community mindset was central throughout Mwamba’s childhood.

“Whatever I had was not my own personal belongings,” Mwamba said. “It belonged to my siblings as well.”

Shirts were shared back and forth. All 10 people fit into a three-bedroom house.

Growing up in an African country was fun, Mwamba said, but dinner time was especially fun.

“We ate together,” he said. “There was no such thing as you having your own plate, your own food. Everything was put together. Just imagine, you cook, let’s say for instance rice and some kind of chicken stew, and everything is put on a big platter, and we all sit around as kids and we eat using our hands, and that is how we share our meal together.”

Mwamba said he learned self-discipline young. He and his siblings went to Catholic schools – one for the girls and one for the boys. School ran Monday through Saturday from 7 a.m. to 1 p.m. Sunday was church.

They walked to school in the sun or rain and wore a uniform of navy blue pants and a white shirt. Mwamba and his classmates had a headmaster who checked the whiteness of their shirts before they were allowed into the school compound.

“Your white shirt had to be spotless,” Mwamba said.

Leaving the Congo

Mwamba grew up playing soccer. In high school he studied electronic engineering and went on to college after graduating high school. Then came the protests.

One day in 1991, around six months later, one of Mwamba’s neighbors and fellow classmates disappeared.

“We were asking, looking for him left and right,” Mwamba said. “He never came home. We never knew what happened to him. He just disappeared.”

That’s when Mwamba said he realized the Congo was no longer safe for him.

“My mom said, ‘You know what, you gotta go,’” Mwamba said. “‘We don’t want you to be next. We can’t afford losing you.’”

Mwamba left in the middle of the night with another student.

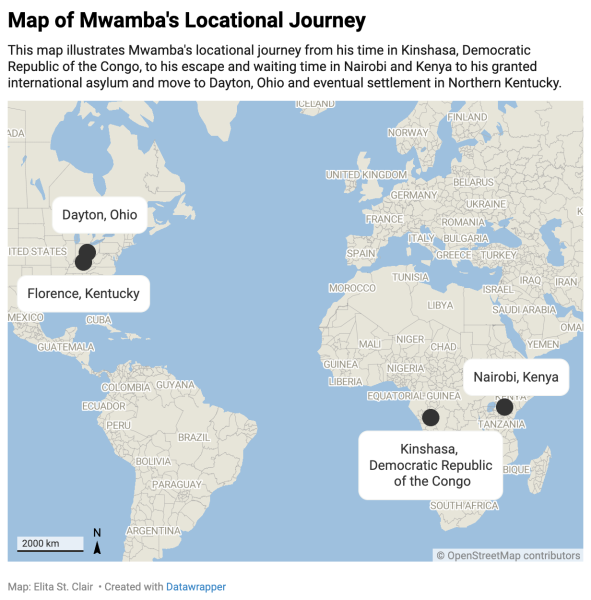

When his plane landed in Kenya, Mwamba didn’t understand a word of the English or Swahili that people were speaking. Once through immigration, Mwamba took the name and number of a Congolese resident his family knew and rode a taxi to the man’s house. The man had a large family with nowhere for Mwamba and his friend to stay.

They spent the night sleeping in the man’s living room and the next morning went to the United Nations’ office to apply for asylum. The high commissioner did not have a place for Congolese refugees to stay yet, so Mwamba ended up homeless on the streets of Kenya’s capital, Nairobi.

Waiting for the refugee camp

Mwamba waited for a year.

“I found myself homeless with no place to stay,” he said. “I felt lost.”

A Catholic services’ organization started to give him $10 a week, so Mwamba and four other friends pooled their money to rent a small apartment big enough to squeeze a mattress in.

One morning, Mwamba went to the French International Center. A French language teacher walked into the hallway where Mwamba was waiting. She asked if she could help him, and Mwamba told her his story.

The woman later connected Mwamba to a Kenyan doctor whose children needed a French tutor. Mwamba was grateful for the job and soon moved into a bigger apartment.

Around a year later, the situation changed again. The Kenyan government decided to relocate the refugees to a remote desert camp close to the Ethiopian border. Mwamba, along with 200 other refugees, boarded a bus and began a new season in the desert camp to wait for their opportunity for international asylum.

The refugee camp

Life in the refugee camp was hard, Mwamba said.

After arriving, Mwamba was given a tent, a shovel, a blanket and a water bottle. He lived there for six months, eating rations of rice and peas. Outbreaks of typhoid and malaria swept through the camp, and sandstorms were a constant frustration.

Eventually, Mwamba was able to pick up odd jobs working construction, masonry and carpentry for the UN officers’ camp as a way of earning a small income. The officers’ camp was made of brick houses with generators, electricity, wells and a large fence around the perimeter. Mwamba spent his income at a small local market to supplement his food.

One day the camp was given a soccer ball. Mwamba and the other refugees created soccer teams as did the other refugee nationalities to play together. These moments of joy brightened the constant challenges that the camp produced, he said.

Asylum in the United States

Refugees could be resettled in four different areas: Europe, Australia, Canada and the United States. The UN arranged Mwamba’s hearing with a representative officer from the U.S. embassy.

The officer read Mwamba’s file and asked him a series of questions about how and why he left the Congo and why he couldn’t go back. Mwamba answered the questions, left the office and waited anxiously for when the camp would post the list of who had been granted U.S. asylum.

On a Monday in the late afternoon, the list was posted on the camp gate.

“I was so, so afraid,” Mwamba said. “So anxious that I could not muster enough courage to go up and read through the names to see if my name was on there.”

He told his friends to let him know if his name was on the list. Mwamba saw his friends return, jumping in excitement over having seen their names.

“Did you see my name?” Mwamba asked. Yes, it was there, they told him. Mwamba then went up to the paper and read his name beside a date. Mwamba boarded the bus and headed back to Nairobi on that date. He went through a medical screening and was given a United Nations travel document.

Mwamba called his parents to tell them he was finally leaving for the United States, and they couldn’t believe it.

“I wouldn’t lie to you,” he told them. “I’m really leaving.”

The day came. In 1993, Mwamba boarded a plane bound for the U.S. with 200 fellow refugees.

“We were all singing praises and hallelujah because we were leaving behind a very harsh life and potentially going into the country of Uncle Sam, the country of opportunity,” Mwamba said.

The group landed on March 3 at Kennedy International Airport in New York.

The American Baptist Church Association, which sponsored Mwamba to come to the United States, picked him up at the airport and provided a place for him to stay until his work permits and Social Security cards came in. It helped him get an apartment and paid his first month’s rent.

Mwamba had learned English and Swahili in Kenya, and now in a new land Mwamba became his group’s official translator, but the differences between American and Congolese culture still led to culture shock.

Helping others

In Dayton, Ohio, Mwamba went back to college at Sinclair Community and Technical College and received an associate degree in electronic engineering technology. Mwamba lived in Dayton for six years before relocating to Northern Kentucky.

Mwamba married his wife on July 5, 2003, and later earned a bachelor’s degree in biblical studies from Cincinnati Christian University. Mwamba said he knew his calling was to be a pastor.

“At age 12, I had a dream,” Mwamba said. “In my dream, I was in front of a crowd with a microphone in my hand, and I was preaching to that crowd.”

Mwamba started attending Christ’s Chapel Assembly of God. after moving to Northern Kentucky and years later his calling became tangible.

“Pastor Mwamba was the first person from the nation of Congo to live in Northern Kentucky,” Terry Crigger, senior pastor of Christ’s Chapel said. “My first memories of Pastor Mwamba were how passionate he was for Jesus, as well as his heart for prayer and evangelism.”

Cadet Katulushi, a pastor from the Congo, and his wife became an intrinsic part of Mwamba’s journey. Together with Crigger they founded a service called the French Parent Affiliated Church for Congolese people coming to the United States who do not feel comfortable with American churches, language or culture.

President Mobutu was forced into exile in 1997 and died soon after, but immigrants from the Congo continue to travel to the U.S. to build a better life for themselves and their families.

“We determined it was worth considering starting a French PAC because our area began to experience extensive growth of French-speaking Congolese families,” Crigger explained. “Our area provides a strong economy and specific jobs that make it a favorable destination for minorities looking for a way to make a decent living.”

The church started as a Bible study at Katulushi’s home and then grew into a formal church service after about six months, with Katulushi as head pastor. The goal of this service, as seen on the church’s website, is to help “Edifier la foi, les familles et les amis” – “building faith, families and friends.”

Mwamba oversees the service, helps new Congolese immigrants adjust to life in Northern Kentucky and Cincinnati, provides connection between the French and English language services and creates a link between Katulushi and Crigger.

“He has become a father to so many people,” Patrina Mwamba, Mwamba’s daughter, said. He has helped foster an environment where “being Congolese in common definitely helps make the mini-Congo that is here, building that community so that [they] have a home away from home.”

Mwamba’s hope is now to help Congolese immigrants learn English and move to English services. Mwamba talked about the vision he has for the French PAC, saying he wants “to see all of our congregation blend in. We can still be distinct in the way we worship and the way we do things but achieve unity in spite of diversity.”

“We are having a great impact in the community so far as the people whose lives are being changed and transformed by what we are offering to the community,” Katulushi said. “We hope to see more people come to know Christ and grow in faith,” and provide help to those coming to the United States not to make the same mistakes they did when they came here.

Church attendee Adoni Mbengami, a Congolese immigrant, said being part of the church is a beautiful experience. “Having a venue where we can actually worship God in Lingala and in French helps us continue to serve the Lord while our English level is improving.”

Now, as Mwamba looks back on his journey, he said he learned that God was always with him.

“I wish I could go back in time and tell that to the younger Mwamba, what he doesn’t know about today,” Mwamba said. “That it’s going to be all right.”