Every morning between 7 and 9:30 a.m. the children of NKU faculty, staff and students arrive on the first floor of the Mathematics, Education and Psychology Center. Some of them might come to the window to say goodbye to their parents, then breakfast is served.

The children spend their weekdays at Empower Learn Create (ELC), a childcare program with a mission: to serve members of the NKU and larger communities, providing their children with quality education while their parents work and study. It might be the most visible childcare resource for parents on campus.

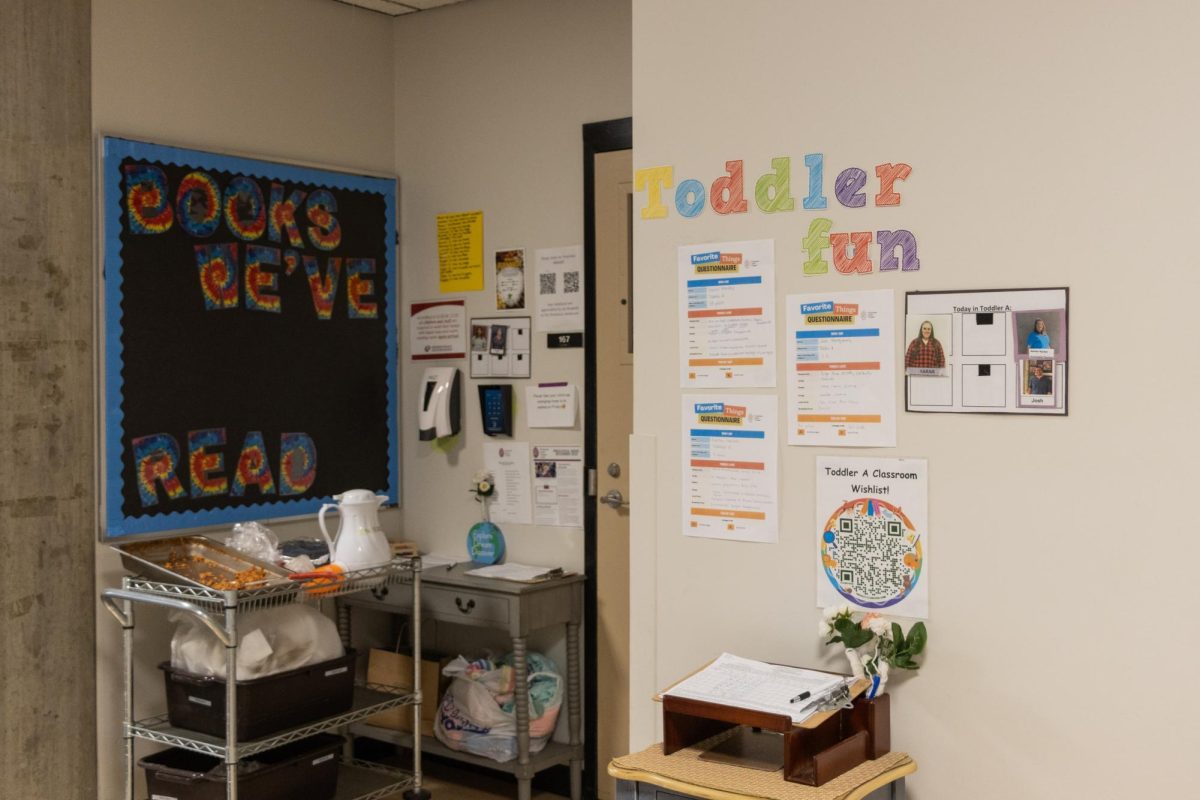

The NKU location currently offers three classrooms: Toddler A for children aged 12 months to two years old, Toddler B for those between two and three years of age, and one preschool class for three- to five-year-olds. The morning would see the classrooms split into two smaller groups that rotate time with a teacher, as well as a group meeting where the whole class is involved. The children then break for lunch, followed by a rest period from 1 to 3 p.m. Afterwards, they are woken up for snacks and to be picked up by their parents.

ELC has a constructivist approach to early childhood education according to Executive Director Barb Herron, which means children would have an open-ended environment with a structurally balanced curriculum.

“We place high priority on the social and emotional lens. We believe the foundational part of learning is building social and emotional skill sets,” Herron said. These skills involve children learning to cooperate with others in a group setting, regulate their emotions, solve problems and think independently with some help from teachers.

Empower Learn Create traces its origins to the University of Cincinnati in 1975, when a group of students came together to propose a childcare program for their children. In 2018 as NKU’s early childhood education center was closing, ELC swooped in for a takeover after hearing demands from the community, Herron stated. The program will turn 50 in 2025.

ELC takes pride in a low student-to-teacher ratio, with a current total of 20 children at the NKU location. The maximum ratio is 10:1 in the preschool class, 5:1 in Toddler A and 7:1 in Toddler B. However, the program—as with other early childhood programs in the area—is struggling with severe staff shortage. To supplement the gaps, NKU’s ELC is employing two student workers per classroom, who make $10.35 an hour according to Herron.

Joshua Montgomery, a middle grade education, English and history triple major, is one of those students. For over two years, his daily work at ELC has involved playing with the children in Toddler A and helping teachers transition between activities more smoothly. Initially he chose ELC to gain more teaching experience as required by his major, but over time he has gotten to know the children and see them grow.

“It’s been a lot of fun,” Montgomery said. “It’s one of the things I get to look forward to during the day.”

At one point Montgomery was working full time at ELC, but then had to cut down his hours in order to better balance work with school.

The number of college graduates in early childhood education have dwindled over the years because of hard work and low pay, Herron explained, so the field as a whole has been scrambling to find credentialed teachers. Working with children in the program would provide good firsthand experience for students of early childhood education and psychology, but the modest wages can pose an obstacle to long-term retention.

A 2021 report by the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy puts the annual earnings for childcare workers that year at $20,423, which falls below the poverty line. 26-40% of childcare workers were estimated to have left their jobs before 2020, and turnover only worsened with the economic downturn incurred from the COVID-19 pandemic, which disproportionately impacted workers of color.

The same report estimates the average cost of care in a mid-to-large-sized center at nearly $8,890 per year, an unaffordable cost for most parents. 2020 childcare costs in Kentucky accounted for 22-35% of a single-parent household’s median income, according to the nonprofit Child Care Aware of America.

Herron applauded Kentucky’s 2022 Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP) legislation to eliminate the cost of care for childcare workers, meaning the children of workers can attend the same center free of charge. “Kentucky has done a lot for early childhood [education] that I’m grateful for,” Herron said, adding that the CCAP legislation is a good incentive to attract more people to the field.

For its part, Empower Learn Create is partnering with other programs to alleviate the burden of childcare costs, including EC LEARN, Resilience Children and Family Project, and NKU’s Parents Attending College (PAC). The latter offers resources for student parents that include employment, case management, referrals to community services and monthly family events, said PAC Coordinator Karis Hawkins.

In addition, the Child Care Access Means Parents In School (CCAMPIS) grant reduces the cost of childcare for NKU students with children, not just for the on-campus ELC location but also any childcare center of their choice. To apply for the grant, students need at least six credit hours of enrollment, a minimum GPA of 2.0 and Pell eligibility. The grant is currently assisting 12 students, according to CCAMPIS Coordinator Jeannie Ritter.

“Childcare can be very expensive and the grant can be a great resource for parents at NKU,” Ritter said.

In terms of finance, ELC has its own challenges to contend with. The program’s funding comes primarily from the children’s tuition and fundraising efforts, but at current rates it is not enough to sustain the highest-quality education possible, Herron said.

NKU students, faculty and staff receive discount rates of $216 per week for the Toddler A class, $201 for Toddler B and $185 for the preschooler program. The prices are higher by $10-11 for community members. ELC tuition has not been raised since 2019, but it is scheduled to increase in 2024 as pandemic-era federal stabilization grants expire.

The area in most significant need of funding is the playground, which according to Herron is constructed mostly of concrete (black fence surrounds the playground area to protect the children’s privacy). To equip the playground with shades, rain shelters and green spaces, ELC would require a total of $75,000. The first phase could cost about $27,000—ELC has been awarded $10,000 from the state to use exclusively for health and safety enhancements, which leaves a fundraising goal of $17,000 for the program.

In spite of the program’s financial needs, Herron is committed to providing quality early childhood education that goes beyond daycare.

“Daycare meets the needs of the day for parents, but oftentimes the needs of children get pushed aside. What children need is to have committed, educated teachers who know how to motivate them, can connect with them and provide an environment full of joy,” Herron said.

Children’s first five years lay the foundation for their mental and cognitive development, she added. “Sometimes I like to tell my teachers that they’re not teachers—they’re brain builders.”

As of the moment, Herron is grateful to continue building relationships with other departments at NKU to give the children the best possible experience, such as taking them to ball games and the Haile Planetarium. “It’s been sort of starting fresh again lately, building those partnerships. I’m excited to see what more we can do on campus.”