Hidden history: Juneteenth celebrated in NKY

June 18, 2023

Nestled across the street from Hofbräuhaus German restaurant, crowds of people congregated around East Southgate Street in Newport Friday evening.

Echoes of jazz music rang through stereo speakers, laughter and hugs reunited old friends, fried chicken and barbecue were piled high on paper plates and folding chairs brimming with people filled the street.

The Newport History Museum at Southgate Street School was the bustling site of Newport’s Juneteenth celebration.

Four walls of history

Southgate Street School was the only public school open to African Americans in Campbell County following the Civil War.

In 1865, the federal government initiated the Freedmen’s Bureau, and one of this agency’s responsibilities was to establish Black schools in former slave states, like Kentucky. In 1866, a Newport school for African Americans was opened; when federal funding ran dry, the school closed.

In 1870, five years after the end of the Civil War, the property of the future Southgate Street School was purchased, and it was officially opened for classes in 1873. The first teacher was Elizabeth Hudson, who earned a salary of $35 a month. As the school’s population grew, more teachers were hired.

The school officially closed in 1955 following Brown v. Board of Education’s U.S. Supreme Court ruling, which said that segregated schools were inherently unequal.

Decades later, the site of the school became a historic museum where guests can see artifacts and get a glimpse into what African American students experienced in the classroom.

NKU students share knowledge

Friday night’s celebration also included the unveiling of a special Juneteenth exhibit created by NKU students.

Early in the spring 2023 semester, the Newport History Museum at the Southgate Street School approached NKU’s Master’s in Public History program—specifically the director, Dr. Brian Hackett.

The museum’s request was for students to put together an exhibit about Juneteenth. Hackett, who teaches the exhibits class and has an extensive history in working with museums, quickly mustered together a group of interested students in his exhibits course.

“[The students] took it upon themselves to first explain what Juneteenth was and how the name came about, and then how it’s important—not just as an African American holiday, but as a holiday for all Americans,” Hackett said.

Through sessions of independent research and collaboration with classmates and faculty, the masters students created 10 framed panels. Three distinct themes were featured in the exhibit: promise delivered, promise denied and promise revisited.

Hackett believed it was important to put history into context and attempt to paint a full picture of the events surrounding Juneteenth.

“I think the students are trying to awaken us all that freedom for all Americans means every American, not just a few,” Hackett said. “These people who fought for their freedom are American heroes, despite what the color of their skin said or what people believed.”

Onlookers to Friday night’s unveiling were struck by the completeness and honesty put into the exhibit. As one visitor snapped photos and carefully read the framed words, he turned to Hackett. “This is impressive,” the man said. Hackett responded that he couldn’t take any of the credit and diverted the praise to the students.

Christopher Riehl, one of the master’s students who collaborated on the exhibit, reflected on his knowledge of Southgate Street School as a child.

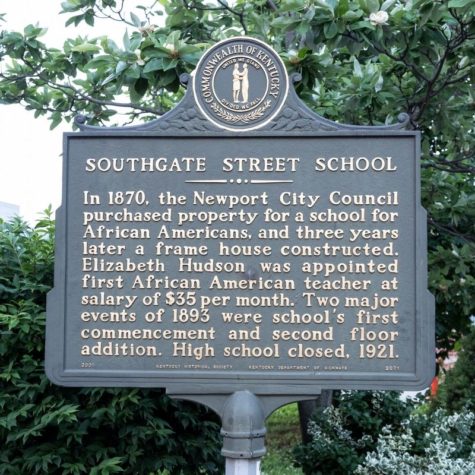

Growing up in Bellevue, Riehl remembered passing Southgate Street School while on walks with his mother around Newport. This was before the school was refurbished into a museum and the only symbol that stood out front was a historical marker.

“My mom always made it a point to walk down—I call it an alley, it’s a street—and we would admire this building and read the placard out front,” Riehl said. “She would always say, ‘Wouldn’t it be awesome if they did something to the building and opened it up and you could see what was inside?’”

The moment came full circle for Riehl as his work hung on the walls of the present day museum.

Another student participant, Erin Durstock, was tasked with researching and writing about General Order No. 3, which proclaimed that all Americans were free following the end of the Civil War.

“As a white person writing about a predominantly Black experience, I had to make sure I got it right and was writing in a lens that was impactful for all Americans, same as General Order No. 3,” Durstock said.

Riehl and Durstock both shared the sentiment that before their undergraduate experiences, they knew very little about Juneteenth and the events that transpired on June 19, 1865. Now, displaying their work as master’s students, they hope to see people of all identities increase their knowledge of the holiday, too.

Recognizing freedom with Jubilee Day

One guest in attendance on Friday night, associate professor and director of Black studies Dr. David Childs, reflected on the founding and significance of Juneteenth.

The purpose of Juneteenth, Childs said, is to celebrate the emancipation of enslaved people in the U.S. While the holiday originated in Texas, it has since spread throughout the country.

On June 19, 1865, Union General Gordon Granger announced General Order No. 3 to the people of Galveston, Texas. The order proclaimed that all enslaved people in Texas were free.

While the Emancipation Proclamation was passed by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863, saying that all enslaved people under the Confederacy were free, this did not give everyone freedom, Childs pointed out. Only when Union troops captured a Confederate state would those enslaved people be free.

“After the Emancipation Proclamation, only about 500,000 enslaved people were actually free out of 3.9 million. So really, it wasn’t until 1865 that those last enslaved people got their freedom papers,” Childs said.

In 2021, the Biden administration sanctioned Juneteenth as a federal holiday, which Childs said took a certain political climate.

“The idea of freedom and liberation are hallmarks of what it means to be a U.S. citizen from the beginning,” the director said. “Folks had to make the case to say, ‘Hey, this is not just an African American holiday, this is an American holiday.’”

Childs felt the protests surrounding the death of George Floyd also played a large role in the holiday’s sanctioning. Floyd was killed by a Minneapolis police officer in 2020, after the officer kneeled on his neck for nearly 10 minutes.

“There’s a lot that has been hidden that we’re just now uncovering,” Childs said. “A lot of people are not ready to accept the ugliness that was in this country… People don’t want to deal with that. That’s why we took so long to push Juneteenth through.”

As a young African American child who grew up in the inner city and went to an impoverished elementary school, Childs has taken strides to maintain his love for learning. He recalled not knowing much about Juneteenth until he became an adult, when he took a deep interest in history.

Today, as the Black studies director and history professor, Childs continues sharing his knowledge and encouraging openness and transparency of our history.

“We’re not teaching diversity to make people feel bad about who they are; we’re teaching diversity because it makes us better people.”