NKU’s 2022 Annual Campus Security Report for 2021

Understanding sexual assault on NKU’s campus

Sitting down with University Police, Title IX and Norse Violence Prevention to discuss crime on campus and the complexity of reporting and investigating sexual assault.

November 18, 2022

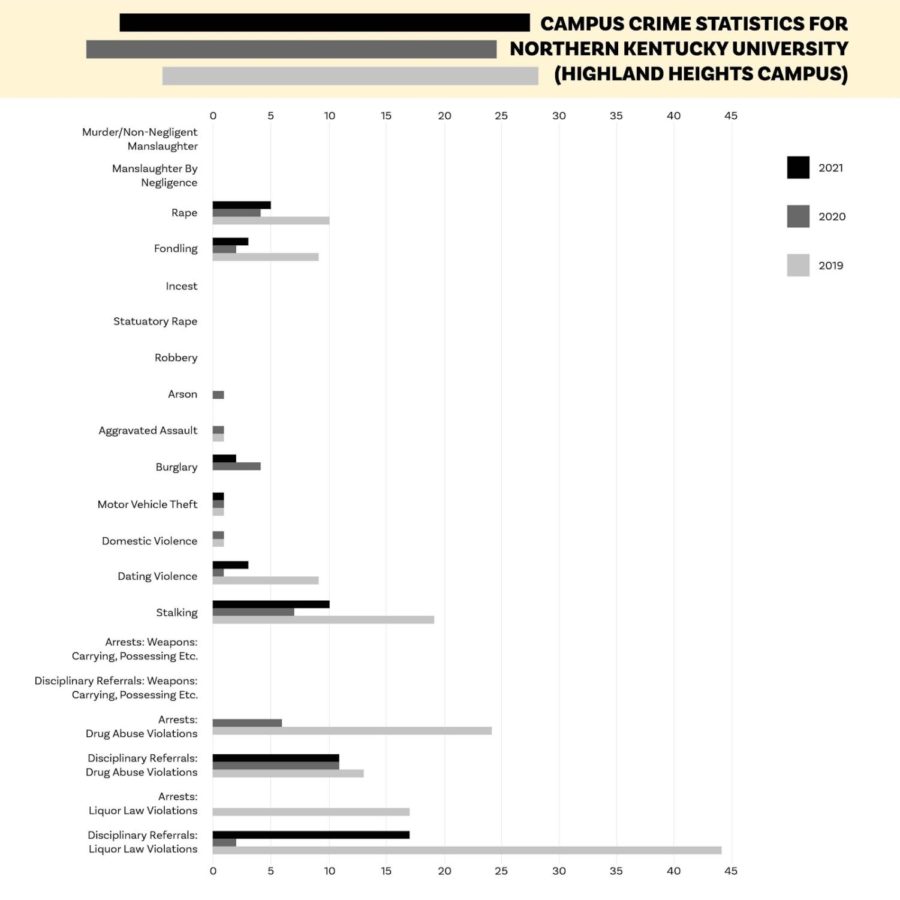

NKU’s Annual Campus Security Report was recently released for 2021; the report is a 75-page document that ultimately displays statistics on crimes that were reported within the range of campus property. For the year, crime appeared to be fairly low; however, 10 instances of stalking and five reports of rape were filed.

University Police Chief John Gaffin said he was fairly satisfied with the numbers included in the report, but the year may not be the best example of a baseline for campus crime. With 2020’s statistics being amidst the pandemic and 2021 still being a hybrid year with a lack of normalcy, Chief Gaffin cited the reports listed for 2019 as the most accurate, as 2019 was the last year to have a typical number of students on campus.

To compare universities of similar sizes and locations, Eastern Kentucky University reported 16 incidents of dating violence, 8 cases of stalking and 13 cases of rape, and Western Kentucky University reported 4 cases of rape with no report of stalking or fondling. For Ohio, Miami University’s report included 18 cases of rape, 9 fondling and 13 stalking incidents. University of Cincinnati included 6 instances of rape and 11 reports of fondling at the Uptown campus but later detailed there were 60 reported rapes that occurred at an “unknown campus.”

For NKU’s university police and the office of Title IX, one of the biggest challenges in understanding these crimes is the lack of reporting. While Gaffin said he would love to see the statistics reach a lower point and the ultimate goal is to see zero sex crimes, this might not be realistic.

“As reporting goes up, people are more comfortable in coming and making those reports. The higher the numbers go, hopefully the better snapshot we get of what’s actually occurring. If those sexual assault numbers went to zero, in a way I would be concerned,” Gaffin said. “That would mean no one reported anything to us and we still feel pretty confident that these crimes are occurring.”

Gaffin said that as other campus resources work to provide support for students and help them find their voice, reporting continues to go up, which, counterintuitively, isn’t a bad thing.

One of these resources, Norse Violence Prevention (NVP), is discreetly tucked away in a corner of Albright Health Center’s second floor. NVP is an advocacy service for students impacted by sexual assault. Director Kendra Massey, with her gentle voice and inviting office, discussed the impacts of sexual assault on students and what NVP is doing to support students.

Massey said NVP is unique because it is totally confidential. The center has no obligation to report a student’s concerns to any other group, and they also have no stake in whether a student decides to file an official report or not. Massey believes that a majority of students who come to the office and seek support for their experiences do not choose to file an official report or undergo a criminal or university investigation. This can be for a plethora of reasons according to the director.

“Sometimes people just want to move on and they think going through that process is going to prolong the focus. Sometimes it’s that they have concerns with how anonymous they’ll be through the process and they fear that people will find out about it. One thing I hear a lot is not knowing what the outcome will be,” Massey said.

No one can definitively tell a student what the outcome of their case will be, Massey said, and oftentimes what a student wants to happen can change and shift throughout the process.

Title IX investigator Morgan Keilholz admitted the federal process of university investigation is not exactly student friendly. If a student wants to report a sexual crime or harrassment they have endured, they must fill out an online form, complete with their signature and checking a box that they give permission to the university to move forward with an investigation. The process can be lengthy and daunting; in some cases a university hearing can occur where the victim can be put under live cross examination.

Massey said in most university investigations if a respondent is found responsible they may be suspended or expelled from the university. In some cases, though, it’s possible that someone found responsible is still able to be a full-functioning student at the university. The director said on some occasions, instances like these can be another deterring factor for why future victims do not want to report.

Chief Gaffin pointed out that the evidentiary standard for a Title IX proceeding is lower than that of a criminal justice proceeding, which is why some students will opt to proceed with Title IX only. For a respondent to be found responsible through Title IX, only a preponderance of evidence is needed, meaning the decision maker is at least 51% sure the individual is responsible. In the criminal justice system a defendant must be found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, which is incredibly harder to prove in sex crimes that often come with little evidence.

“Issues of proof are really hard. Generally these offenses occur behind closed doors. There aren’t impartial witnesses or recordings, so you have—from the beginning—a really difficult issue to prove,” the police chief said.

Gaffin said the criminal justice system struggles to balance a defendant’s rights and assurance of due process with valuing a victim’s rights and not making the process so intimidating that it does more harm than good. This is why the chief thinks avenues like Title IX are so valuable, even if the system isn’t perfect. He pointed out that outside of the university setting, Title IX does not exist, and through its flaws it is meant to serve students with university-appropriate remedies, like suspension and expulsion, that the police do not have the power to act out.

Massey and Gaffin both recognize that even at the end of a formidable process, the victim is still not healed of their experience. NVP focuses on meeting with students throughout the entirety of their journey and ensuring they continue to move in a positive direction amidst their decisions to report, go to hearings or see an enacted outcome.

“We try and talk through what their expectations are going in, and then how they can make sure that they have good support regardless of what the outcome is. Even if the outcome is what they wanted it to be, they’re not healed,” Massey said.

This is why NVP continues to offer support long after a hearing or investigation is marked as closed. The center can connect students with counseling, offer a survivor support group, meet with students to talk through coping mechanisms or discuss a safety plan if they feel unsafe on campus or even outside of NKU.

Gaffin says the university police are working to stop these crimes on the front end instead of working to remedy them on the back end, and Massey and NVP are working to advocate for supportive responses toward students that come forward rather than responding with blame or skepticism.

“Our goal is just to support [students]. If they do want to report, we can support them through that whole process so that they have one person who is there through every step of that,” Massey said.