Your donation will support the student journalists of Northern Kentucky University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

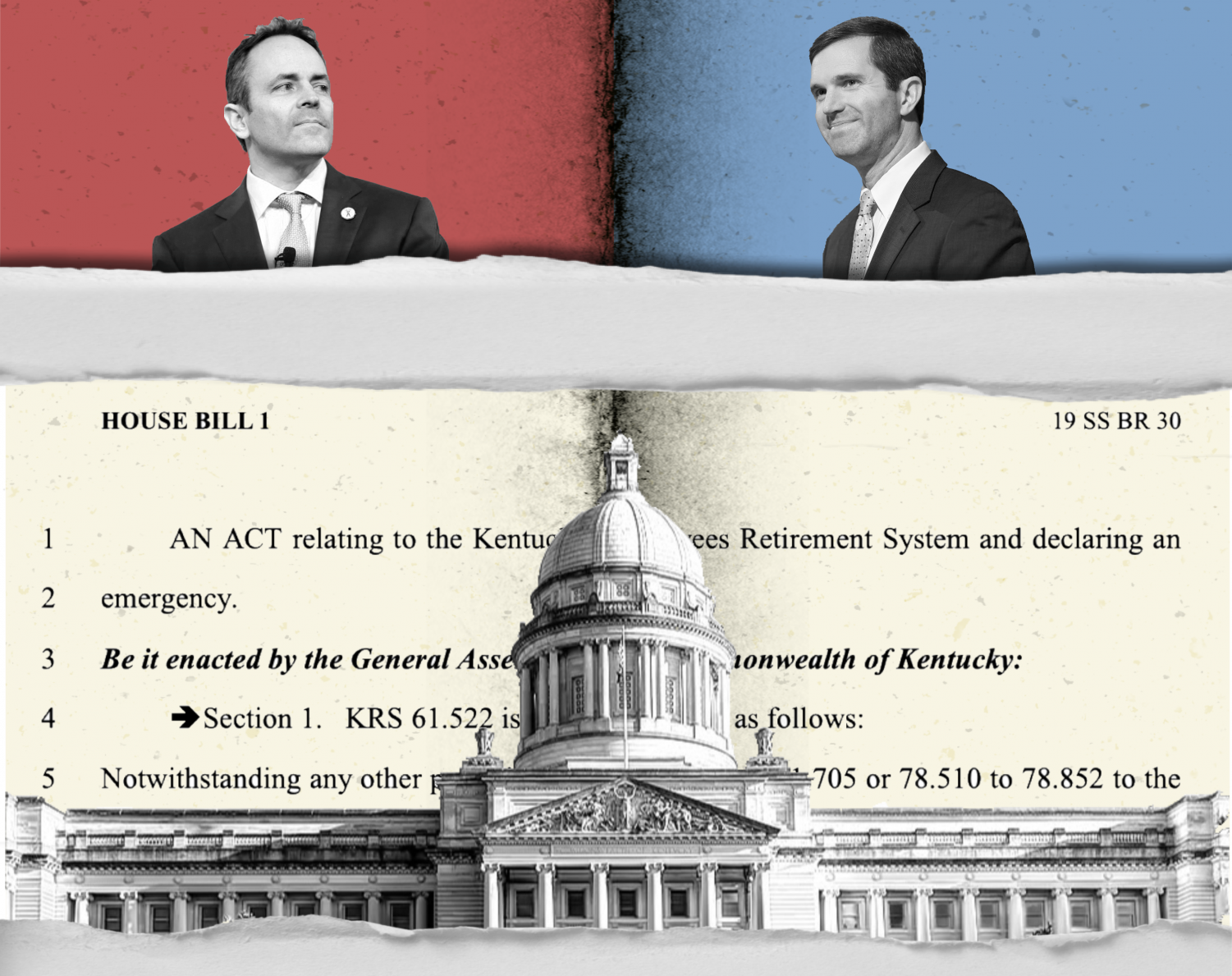

Amid pension crisis, Beshear offers hope

What went wrong and what's next?

January 29, 2020

After Kentucky educators marched on Frankfort on April 2, 2018 in the wake of the final approval of Senate Bill 151 (SB 151), the controversial proposal was later overturned by the Kentucky Supreme Court for being unconstitutional.

It wasn’t the beginning—nor end—of the fight for public pension reform in the Commonwealth. But now, reform has taken a giant step toward the finish line with Governor Andy Beshear’s announcement on Tuesday night that he would fully fund Kentucky’s pension system in an attempt to whittle down the system’s $43 billion debt.

Beshear and the future

NKU Assistant Vice President Government, Corporate & Foundation Engagement Adam Caswell said it’s still too early to tell how the pension system will look under the Beshear administration.

Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear delivers the budget address to a joint session of the state legislature at the Kentucky State Capitol in Frankfort, Ky., Tuesday, Jan. 28, 2020. (AP Photo/Timothy D. Easley)

However, Beshear announced that he would fully fund Kentucky’s pension systems during his 2020 budget address on Tuesday night. It was one of his biggest campaign promises.

According to the proposal, Kentucky Employment Retirement System (KERS) will receive an additional $56.5 million for the 2021 fiscal year and $63.9 million in the 2022 fiscal year. In addition, healthcare for state employees will receive $9.3 million in 2021 and $34 million in 2022, according to the Lexington Herald-Leader.

“My promise to you is simple; I will always contribute the required contribution amount to our pension plans,” Beshear said in his address. “By doing this year after year, we’ll protect your pensions and guarantee each of you a solid retirement.”

The Republican-controlled legislature of the past two years tried to cut funding to what was already one of the worst-funded pension systems in the country. Their attempts were met with protests from state educators and employees, and former Governor Matt Bevin’s attempt to cut pension funding was the biggest reason he was voted out of office, according to Time Magazine.

How did we get here?

Data from the Associated Press shows Kentucky’s public pension plans now total over $43 billion in unfunded liabilities as of 2019—a stark contrast to when pensions were fully funded in 2000.

Primary reasons for the accumulation of debt over the past two decades can be attributed to underfunding and risky investments.

Between 2003 and 2016, the state’s governors and the General Assembly failed to create enough money for state employee and teacher pensions, according to the Courier-Journal.

Instead, lawmakers used pension money for roads and schools since other tax revenues in a recession economy could not fund those projects on their own, according to David Sirota in a PBS Frontline special report. During those years, governors and lawmakers shorted pensions by $3.8 billion—and, in fall 2009, invested a portion of the pension’s portfolio into Wall Street hedge funds.

A December 2017 lawsuit filed in Franklin County Circuit Court by eight current and former public employees alleged that Kentucky Retirement Systems (KRS) made $1.2 billion in investments with hedge funds that lacked transparency and had high fees. The lawsuit also alleged that KRS obscured the severity of the pension crisis with false assumptions of future returns from the hedge fund investments.

Additionally, a 2017 report from Philadelphia-based consulting company PFM said a big reason for Kentucky’s rising debt was because of lawmakers’ inaccurate assumptions in the state’s employer funding.

The state expected employer funding, which is based on a percentage of the employer’s payroll, to grow—but it didn’t.

According to PFM’s report, even if the state and employers made all the required payments to the funds each year, those payments wouldn’t have been enough to pay off the annual interest on unfunded liabilities.

Bevin’s impact

Kentucky Governor Matt Bevin announces his intent to call for a recanvass of the voting results from Tuesday’s gubernatorial elections during a press conference at the Governor’s Mansion in Frankfort, Ky., Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2019. (AP Photo/Timothy D. Easley)

Bevin outraged Kentucky teachers—including NKU professors, who protested with students outside the Student Union in 2018—and drew scrutiny from then-Attorney General Andy Beshear when he signed SB 151 into law on April 10, 2018.

Related: Cuts to come? Lawmakers, NKU wait for Bevin’s budget

SB 151 was controversial for a slew of reasons. The bill—which was overturned by Kentucky’s Supreme Court—would’ve seen increased contribution rates for retirement benefits and an end to the inviolable contract for new teachers.

In the bill, the retirement eligibility for future teachers increased to age 65 with five years of service, or when the employees’ combined age and years of service equal 87.

At the very least, SB 151 would have caused a $20 million hit to NKU’s finances.

Pension and NKU

NKU currently has 700 employees in the KERS—the most of any university, according to the Lexington Herald-Leader. The state placed NKU in KERS in the 1970s.

In 2019, NKU’s pension payment was $18 million. This year, the payment is $31 million under the current plan, Caswell said in an interview with the Herald-Leader.

According to Caswell, no university could currently afford the multi-million dollar cost to exit the pension system with a lump sum payment. He expects most will choose the 25-year repayment plan.

“Public pension reform is arguably the greatest financial issue that the state and NKU have faced,” Caswell told The Northerner. “Over the last couple of years, we have been faced with what could be financially devastating contribution rate increases.”

Caswell said NKU currently pays 49 cents on every dollar it pays their pension employees. Without the action by the legislature during last summer’s special session, it would’ve gone up to 93 cents.

“It’s an unsustainable system for NKU,” Caswell said. “But fortunately this past summer, the legislature passed House Bill 1 (HB 1) in a special session that gave us options of how we may address the pension system in the future.”

The first option, according to Caswell, would be to do nothing. But by sticking with the status quo, it would leave NKU in a system where it would be subjected to increased contribution rates.

“It would be a financial blow to the university,” Caswell said.

The second option is a hard freeze, where all KERS employees will exit the pension system. NKU would then owe the retirement system an unfunded liability that it would pay off over time.

The third option, a soft freeze, would allow NKU to leave all of its Tier 1 and Tier 2 employees (employees that entered the pension system before 2014) in KERS, but have Tier 3 employees (employees hired after 2014) exit the system. However, a soft freeze still comes with an unfunded liability that NKU would have to pay back to KERS over time.

Related: Bills could freeze NKU’s payment or help school leave system

NKU has an outside consultant advising on the financial ramifications of all three choices to determine the university’s best option. In order to potentially leave KERS, NKU will first need to retrieve its unfunded liability information from the system. The university plans to receive that by Jan. 30.

“They’re required by law to give us our unfunded liability information no later than 60 days after Jan. 30,” Caswell said. “Once we have that information, we will be able to assess all the options that exist currently for us to exercise and will work with our Board of Regents.”

Who’s affected?

The James C. and Rachel M. Votruba Student Union.

NKU, Western Kentucky University, Eastern Kentucky University, Murray State University, Kentucky State University and Morehead State University, along with other quasi-governmental agencies, are directly affected by the pension crisis, according to Kimberly Wiley, Chair of the Staff Congress Pension Committee.

Caswell said that NKU hasn’t experienced as significant of a blow as other universities due to its relatively young age—but that doesn’t mean it’s not struggling.

“If you look at the unfunded liabilities of all the universities in Kentucky affected by the pension system, NKU is on the lesser end,” Caswell said. “We haven’t had as large of employee bases over time, but that doesn’t mean that our number is insignificant.”

According to Wiley, Tier 1 and Tier 2 employees will be affected the most, with the majority of Tier 1 employees losing a significant amount of money over their years of retirement.

HB 1 requires NKU Tier 3 employees to exit the public pension system by June 30, 2020 and enter NKU’s defined contribution plan it has through Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America (TIAA) on July 1.

Wiley said before the loss of employee choice in HB 1, employees could choose if they wanted to stay in the system, or roll over into the mandatory TIAA defined contribution plan.

“With that gone, we don’t know where we’re going,” Wiley said.

What can employees do?

NKU’s Staff Congress formed the ad-hoc Pension Committee to represent and provide information assistance to all staff regarding pension issues through education and resources for managing their pension.

“We wanted to make sure all staff employees were informed and that they knew what was going on,” Wiley said.

According to a Pension Committee handout, the committee’s main goal is to help NKU staff learn how to navigate the KRS Self Member Service, as well as help Tier 1 and Tier 2 staff learn how to access and use the Benefit Estimate Calculator to determine their monthly retirement benefit estimate.

“Our goal is to keep employees educated,” Wiley said. “There are a lot of employees that haven’t even logged into the current system.”

According to Wiley, some employees don’t even know what they have in their pension or where they fall in the system.

In order to educate employees, the Pension Committee had a TIAA representative come to NKU and speak. Additionally, the committee has had monthly help sessions.

“We can’t sit by idly and wait for Frankfort to solve these problems for us,” Caswell said. “We’ve got to be thoughtful in our approach, offer solutions, let them know the various scenarios and be able to make an educated decision at the end.”

“This is arguably the greatest financial decision NKU has ever had to make.”