Your donation will support the student journalists of Northern Kentucky University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

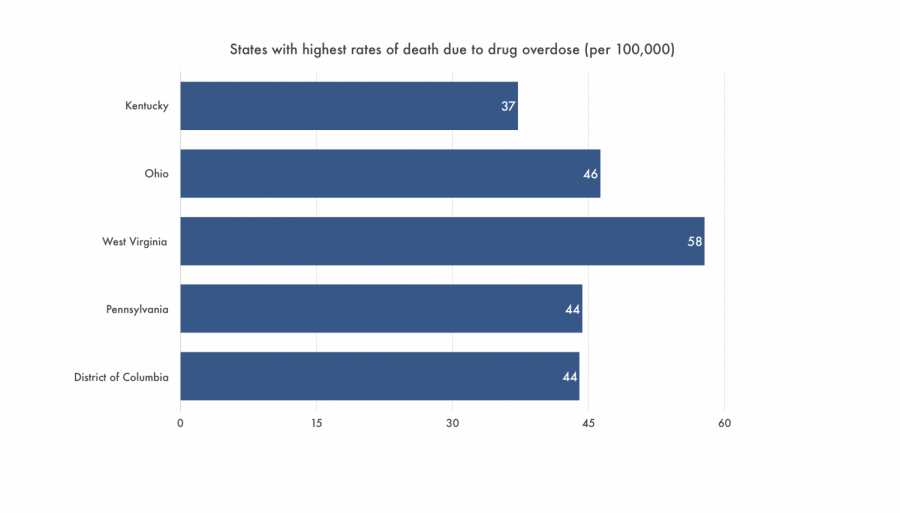

Data sourced from Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

NKU helps fight opioid addiction in Owen County

Kentucky is fifth in the country for highest rates of preventable deaths

September 11, 2019

NKU will extend its intervention in Owen County, Kentucky for opioid substance abuse following the allocation of $1.8 million in federal grants, according to Institute for Health Innovation (IHI) officials.

The grants were awarded as part of the federal government’s aim toward easier access to health services in rural communities. With this extension, the university’s work, which began last November, will continue for three more years.

While the opioid epidemic has spread throughout the U.S., Kentucky has been one of the states hit hardest.

According to a 2019 study conducted by the National Safety Council, Kentucky ranks fifth in states with the highest rate of preventable deaths, the leading cause being officially labeled as poisoning—which is comprised mostly of overdoses.

“When you look at the pattern of overdoses and deaths of people struggling with substance abuse disorder, we are at the epicenter of it,” St. Elizabeth Healthcare Executive Director of IHI Valerie Hardcastle said.

Hardcastle, who has spearheaded NKU’s response to the opioid crisis since its inception in 2018, said the state is a high-risk area due to its large blue-collar workforce and ease of access to heroin.

According to Hardcastle, people with jobs that involve physical labor are more likely to be prescribed pain relievers, an opioid that—if over-prescribed and abused—is known as a gateway drug to harder substances like heroin.

“It’s a perfect storm,” Hardcastle said. “The ease to get heroin here is combined with this huge push to prescribe opioids for chronic pain from that type of labor.”

NKU social work lecturer David Wilkerson has studied the opioid epidemic since the early 2000s, and he said that while the crisis is now being painted as a sudden influx of heroin, it was an issue with a different portrait 20 years ago.

“It was a quiet issue for a long time,” Wilkerson said. “Pain pills aren’t as sexy as heroin. They don’t grab headlines. So, we didn’t know doctors were over-prescribing until years later.”

Hardcastle said the government eventually recognized the pain medicine addiction crisis around 10 years ago and made strides to resolve the over-prescribing.

She said, “So then they cut off that spigot—but that doesn’t solve the problem.”

According to Wilkerson, once you become addicted, the form of the drug becomes inconsequential. What was formerly found at the bottom of a pill bottle was soon rediscovered at the razor edge of a needle.

With the additional federal funding, Hardcastle said NKU will be focused on prevention and early intervention.

For Owen County specifically, she said, that means beginning with the county’s youth.

“Historically, when people show up in the ER with an overdose, it doesn’t happen when they first started taking the drug. It happens 10 years down the line. So, usually, people in their 40s or 50s would show up, and that tells us they started using in their early 30s,” Hardcastle said.

“Now, when you look at the statistics in Owen County, people are showing up in the ER at 30. That tells you they’re starting in school.”

According to Hardcastle, the opioid epidemic is targeting Owen County’s “disconnected youth,” young adults between the ages of 16 and 21 that have minimal employment or educational structure. It’s a demographic in Owen County that was the prime focus for the IHI last year.

As part of his grant fulfillment this past year, Wilkerson provided Owen County High School faculty with training on how to conduct universal health screenings among students to identify those at higher risk of substance abuse.

“Rather than waiting for people getting caught with heroin, it’s looking at people who are maybe using too much alcohol,” Wilkerson said. “And, then, depending on the screening, there would be a brief intervention.”

With the extension in funding, Wilkerson said he plans on expanding the training outside of the high school to also encompass community health professionals in Owen County.

As Wilkerson focuses on prevention and early intervention, assistant professor of social work Dr. Suk-hee Kim is currently working on a plan to reduce the number of overdosing deaths in the county. Because Owen County does not have an in-county hospital, Kim has devised an expansion plan for a local Quick Response Team that will provide emergency assistance in the aftermath of an overdose.

“Owen County is a big county with a lack of resources,” Kim said. “NKU has a lot of resources, so we have the capability of helping our community’s needs. That doesn’t mean we have all the answers, but a collaboration is very critical in overcoming this issue.”

Because a facet of the funding aims to expand the health services workforce, Hardcastle said she is also planning on designing a career path for those looking to provide health services and resources for addiction.

According to Hardcastle, IHI will convert the 40-hour in-person training to become a peer support specialist—currently only based in Covington—to an online or hybrid course that will allow easier enrollment to those throughout Kentucky. She said IHI is also interested in allowing students to turn that program into college credits.

“Our goal is to make this more of a career path, so that if they run those credits through NKU, they can put it towards a counseling degree,” she said.

But while NKU prolongs its involvement for three more years, Hardcastle is quick to note that a change in the culture takes time.

“The percentage of people dying from overdosing, state-wise, has gone down,” she said. “It has went up in Owen County. At this point, we’re just trying to keep people from dying.”

According to Kim, it is when neighboring communities are in moments of dire need that collaboration and support is needed the most.

“This is a community’s agony,” Kim said. “It is not your problem. It’s our problem.”