Your donation will support the student journalists of Northern Kentucky University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

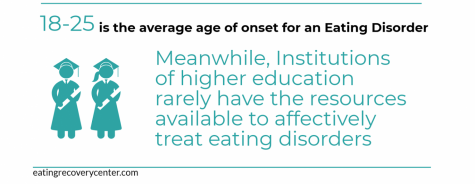

Illustration by Noël Waltz, Information by Eating Recovery Center

Suffering and silenced: The reality of eating disorders on campus

January 21, 2019

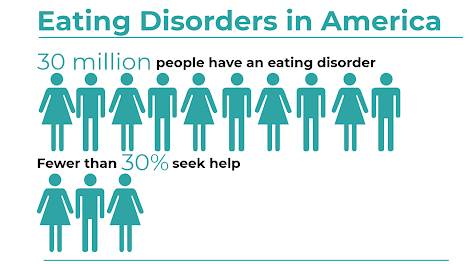

More than 30 million people across the country are struggling with an eating disorder, but only 30 percent will ever seek help. Eating disorders are terrifying, and many college students will unfortunately come to understand that all too well. A few Norse have been willing to tell their stories – will you listen?

Dr. Casey Tallent, national collegiate outreach director for the Eating Recovery Center, explained what consequences can result from the stressful transition into college.

“Students are away from home for the first time. They’re encountering new academic and social structures and they tend to fall into unhealthy methods of coping—which is often an eating disorder for many students,” Tallent said.

Alison Callahan, a senior visual communication design major, was diagnosed with anorexia when she was 8 years old. Since then, her road to recovery has had its ups and downs.

“It wasn’t really a linear process—some months I would be doing really, really well and some months I would just tank and kind of bottom out and it was really rough,” Callahan said.

Attending a university that is two hours away from home and living without the guidance of her parents encouraged her to slip back into these destructive habits.

“At first it was like—‘great! I can do all this stuff and not get in trouble!’” Callahan said, “But then my friends started noticing things and it was a lot harder to trick them than my parents.”

Before heading off to college, a lot of young adults are warned about the “Freshman 15.” For someone who is genetically predisposed to an eating disorder, being fearful of such a weight gain can trigger an eating disorder. For someone already battling an eating disorder, this fear can trigger unhealthy, compulsive behaviors.

Dr. Tallent clarified that this warning is not only harmful, but simply untrue.

“Freshmen students typically gain about 5 pounds on average, which is developmentally appropriate,” Tallent said.

Callahan said this warning is a huge part of why her eating disorder was so intense her freshman year.

“I thought the freshman 15 was something that was definitely going to happen,” Callahan said. “I thought I was going to gain 15 pounds no matter what.”

Vanessa Neiser, a sophomore middle grades education major, was diagnosed with anorexia her senior year of high school. Although she was able to take control of it for a little while, the transition to college resurfaced the issues again.

“When I got to college I was surrounded by so many different people, with the pressure of the adjustment. I just wasn’t used to change at all,” Neiser said. “It really became too much. I just let myself go back to the destructive habits from before.”

Sally Modzelewski, a junior musical theatre major, discovered she had a binge eating disorder around her junior year of high school. Similarly, she saw the disease get worse as she transitioned to university life.

At home, her food intake was relatively monitored by her parents. So, when she moved on campus her freshman year, she found herself eating uncontrollably without the parental guidance. This caused her to gain 40 pounds, something that was incredibly alarming.

“A lot of it was because of how easy it is to get food on campus,” Modzelewski said. “I would go to dinner at [Norse] Commons and just eat plates and plates and plates of food and just couldn’t control myself.”

The stress of her transition to college coupled with the particular stress within her musical theater major had a dramatic effect on the severity of her disease.

“In theatre, they want you to have the ideal body type. At NKU, it isn’t as big of a deal, but we still kind of know it to be true,” Modzelewski said. “So I feel like coming to college really put that on me and made me stress out about that and therefore eat more.”

Many who live with an eating disorder don’t seek help because of the stigma attached to the conditions.. On NKU’s campus, even those who take the step to seek help often do not have access to the resources they need.

Callahan reached out to the Health, Counseling and Student Wellness Center right when she started noticing herself falling back into some destructive habits. They set her up with counseling, but when it was revealed that an eating disorder was her primary concern, her counselor let her know that there was not a specialist in that area.

They referred her to some of the recovery centers in the area, but her insurance didn’t cover any of them, so she didn’t stick with the on-campus therapy.

When Modzelewski sought on-campus resources, she was told the same thing: while counselors were able to help her with some other mental health issues that she was having, they were not equipped to provide help with an eating disorder.

“That’s odd to me, because high school and college are the prime times for people to develop eating disorders,” Modzelewski said.

Tallent said that institutions of higher education have a responsibility to get the message out about eating disorders. She describes ideas for how to do just that.

“They can have outreach events where they get students information about eating disorders. They can offer resources to help to identify eating disorders in students and provide them with local resources,” Tallent said.

Such events are seen in the form of “eating disorder awareness week” and “love your body day” on campuses across the country.

This outreach is important because of the stigma and shame associated with eating disorders.

“When you walk into a counseling center and you don’t see resources available, it can be hard to ask for help it’s kind of silencing,”Tallent said. “I hope that the message that every college gets out is that it is okay to ask for help with eating disorders, that they are real valid issues.”

Lisa Barresi, the associate director of counseling services, said when a student is seeking help with an eating disorder, they make a referral to an eating disorder specialist because the university does not have the resources to appropriately and effectively treat eating disorders.

“Treatment for students who have an active eating disorder is more intensive than what our office can provide. It is usually long-term—can sometimes involve being seen multiple times a week or involve hospitalization,” Barresi said. “It also requires a multidisciplinary approach, including nutritional counseling and other medical care.”

If an eating disorder is not identified as the primary treatment issue, the student can receive ongoing counseling services. All students, regardless of whether or not they have been referred to an outside provider, are eligible to use the crisis services.

A student can access crisis resources by calling (859) 572-7777 or texting 741741.

Local Resources

Eating Recovery Center, (513) 808-9220

Life Worth Living, (513) 257-2409

Lindner Center of Hope, (513) 536-4673