Illustration by Bridgette Gootee

How should you learn about college debt?

NKU grads typically owe $25K as national student loan debt rises

November 28, 2018

“For some reason, they let an 18-year-old sign that much money away.”

Mac Payton, an NKU alumnus, is thousands of dollars “in the hole” for a college degree he said he isn’t using.

“I remember I was walking on my way to class and I had the realization that like, I don’t want it. I had the realization that like, I don’t want to do this for the rest of my life,” Payton said. “Oh, God, and I did a victory lap. So I was already five years in at that point. And I was like, I’m not doing another year, two years, three years and getting further in the hole.”

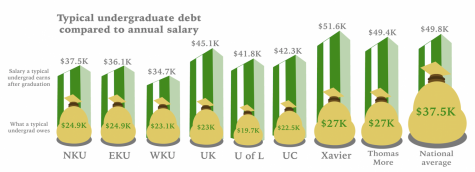

He’s not alone. In total, 44 million borrowers in the U.S. owe over $1.4 trillion in college debt. In 2017, the typical undergrad student owed over $37,000 for their degree.

At NKU, a typical undergraduate could take on about $25,000 in debt by the time they graduate, according to the Department of Education’s College Scorecard.

Two schools of thought are that either student loans are to be avoided at all costs, or that they are an investment in one’s future.

Devin Workman, an NKU junior studying computer science, looks at loans as a buy-in for the future, not a burden.

“For me, it makes sense. It’s all about perspective,” Workman said. “…It’s definitely worth the money comparatively. But if I wasn’t sure about my major, like some people, where they go undeclared all the way to the end—that to me would not be worth it.”

With college debt growing, how can NKU students be sure they’re making the right financial call?

Center for Economic Education

It’s a different economic world now than it was for the previous generation, Dr. Abdullah Al-Bahrani of NKU’s Center for Economic Education said. That contributes to the rise in student loan debt, but there’s more than meets the eye.

“The previous generation will look at the young adults today and say they don’t know how to navigate financial markets and they were better at it,” Al-Bahrani said. “Usually that’s what we hear. But in reality, the financial markets are more complex today and individuals are having to make more decisions on them by themselves independently.”

NKU students owe less for college than the national average, but they also earn less. The typical NKU grad that received federal financial aid makes $37,500 per year, which is under the national average salary for people with bachelor’s degrees, $49,800 according to financial analysts at Korn Ferry.

Some students avoid debt completely, which might reduce the scope of their options, Al-Bahrani said. Still, if that isn’t an option for students, he said he believes student loans can “facilitate receiving or investing in your human capital.”

But that raises questions for students to answer.

NKU undergraduates typically owe nearly $25,000 in student loans, which is under the national average $37,500. The typical NKU grad will make less ($37,500) than the national average college graduate salary ($49,795). “Typical salary” is median earnings of former students who received federal aid 10 years after attending. “Typical undergrad owes” is median federal debt excluding private loans and Parent PLUS loans. Data from the U.S. Department of Education, Korn Ferry financial consultancy, MakeLemonade personal finance site, Debt.org finance.

“You need to know the numbers,” Al-Bahrani said. “You need to know, are you incurring too much debt? Do you know what your average salary is upon graduation? How does that relate to your your loan payment so that the debt isn’t bad?

“The lack of awareness about what the debt is, is bad,” Al-Bahrani said.

So, to ward off financial illiteracy at NKU, the Center for Economic Education is taking a top-down approach.

“Our objective is to educate the general public about how to make financial decisions,” Al-Bahrani said. “And we do that mainly by educating the educators.”

One major change that the program is bringing is a new general education course offered in the spring called “Financial Pathways.”

“It’s our commitment to make sure that our NKU students are also able to navigate the financial world,” Al-Bahrani said.

Financial aid at NKU

For NKU students, Financial Aid Coordinator Travis Hall said in order to accept a loan, students must take an online counseling session with the Department of Education and sign a master promissory note that highlights the terms and conditions of the loan.

Additionally, the NKU Office of Financial Aid reaches out to the broader community through local high schools and educates incoming college students about not only loans, but financial aid in general.

“We try to hit it on multiple fronts,” Hall said. “We try to hit it early in the high schools so that students know to fill out their FAFSA early, and then when they come to the university, we give presentations that say, ‘Okay, if you haven’t done it, this is how you do it. If you have done it, this is what you can expect.’”

Hall said the role of the office mainly entails notifying students about their financial aid opportunities and guiding them in the right direction, but that they don’t specialize in providing students advice about “big life financial decisions.”

Still, Hall said, the office will provide advice to the greatest extent they can.

“We are more than happy to sit and talk to a student about any aspects of not just financial aid, but anything … we will go over anything you want to know about federal financial aid, institutional financial aid, state financial aid.”

The individual

Payton said he conceptually grasped the idea of his loans throughout his college experience, but did not look at the full balance on his account until after graduation.

“The full depth of it did not hit me until after I graduated,” Payton said.

Now, Payton has found an alternate path through Americorps, which provided him loan forgiveness and a platform to explore his passion for educating. Payton acknowledged, however, that not all students are as fortunate in dealing with the ramifications of their incurred debt.

“Do some—for lack of a better term—soul searching, or reflection to make sure that you are in the field that you 100 percent want to do, no questions about it,” Payton said. “You’re okay being in that role from here until the day you die.

“Because the sad thing is, unfortunately you’re going to have to be because of the amount of money that’s going into it.”

Al-Bahrani, a former mortgage loan officer, compared the general attitude toward student loans to the mortgage market between 2002 and 2006.

“People were just getting mortgages because they technically could get them but they didn’t think about the repayment process,” Al-Bahrani said. “And a lot of people blamed the mortgage firms, a lot of people blame the government, but very few blame the individual.”

Workman also emphasized his own personal responsibility he assumed when he signed his promissory note.

“Maybe I’m not most people or maybe I just research obsessively about any purchase. So, that was the biggest purchase I’ve made up to that point in my life,” Workman said. “So, I figured I should probably understand it.”

Al-Bahrani, as well as Workman, agree that increasing education on student loans is the solution to helping the individual understand their debts.

Aside from an online loan counseling session required by the Department of Education, there is no mandatory counseling that comes with accepting loans.

Ashley Tallent, a graduate student who was paying her undergrad loans before she started at NKU, said no one ever sat her down and talked to her about how to use loans.

“I knew to an extent what I was getting into, but I didn’t really have anybody explain to me the interest, and once you get out, you’re really only paying on your interest and not even on your loan,” Tallent said.

She first went into debt to earn her bachelor’s degree in criminal justice at University of Cincinnati, and she began paying the loans soon after she graduated.

Tallent, who is now studying clinical mental health counseling, works at Talbert House addiction treatment center. It’s difficult to work and attend grad school simultaneously, so she said she has looked into federal loan forgiveness programs which work through nonprofits. However, even qualifying for the programs is daunting.

“It honestly sounds very hard to get your loans actually forgiven because you have to pay a certain amount of time on the loans and actually work for a nonprofit that’s covered,” Tallent said.

Tallent feels there could be more education about what kinds of loans are available, how long it takes to pay them back and how interest works.

“I learned my lesson, and I didn’t take as much student loans out this time around as I did in my undergraduate, really just enough to cover my tuition,” Tallent said.

Society’s attitudes

Al-Bahrani said one of the Center for Economic Education’s efforts includes changing societal attitudes about not attending college.

“Part of the work that I do is in high school, we do what’s called career guidance. For years, we’ve pushed this ideology that college is the only way to succeed. That’s not necessarily true,” Al-Bahrani said. “So making students more aware of what their options are in life. So it all comes down to more information to the student.”

In addition to the stigma involved in career choices, Al-Bahrani also talked about the stigma society attaches to discussions about money.

“Money is an uncomfortable conversation,” Al-Bahrani said. “It’s kind of like talking about weight and diets, they have a negative connotation and we need to eliminate that, and it takes awareness and it takes the willingness to have more conversations to make it accessible.”

In analyzing the problem as a whole, Al-Bahrani said it’s on everyone to assume responsibility. He pointed to recent state legislation, House Bill 132, which requires every high school student to take a financial literacy course starting in 2020.

“I think as a society we’re starting to recognize that we need to equip our citizens with more financial knowledge,” Al-Bahrani said.

That acquisition of such knowledge, Al-Bahrani believes, is a responsibility we bear together.

“The responsibility is on the individual, the responsibility is on the educators, the parents and the administration, right? And then finally, government as well, since it’s part of the education process.

“I think there’s enough responsibility for all of us to take it,” Al-Bahrani said.

Northerner Editors Natalie Hamren and Josh Kelly contributed to this report.