Your donation will support the student journalists of Northern Kentucky University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

As student Alex Voland collected student signatures to ‘Save the Early Childhood Center,’ she recalled one student saying that they would miss the kids on campus, laughing and playing. The center is slated to close June 1.

In the wake of the Early Childhood Center’s closure, students work to save it

April 2, 2018

In a small room next to the Early Childhood Center, Samantha Hamilton holds her youngest son on one knee. In front of them are stacks of research and statistics that detail the struggle single parents face while obtaining a college degree.

For her, the ECC has made her feel like finishing her education is possible. Her 1-year-old climbs off her knee and onto the floor, playing quietly with a toy. On the other side of the wall, kids can be heard laughing.

When Hamilton first read the email sent by interim president Gerard St. Amand announcing the ECC’s closure, she said her heart sank. Her immediate reaction was to cry. “It’s getting me emotional right now,” she said, holding back tears.

“It’s one of those things where you have to keep the emotions out of it when you talk to these people, but it’s hard not to when you finally think you’re going to be able to graduate and finally have care for your kids,” she said. “I scheduled summer classes to keep my kids here because I love it that much. It’s like the ground was taken out from under me.”

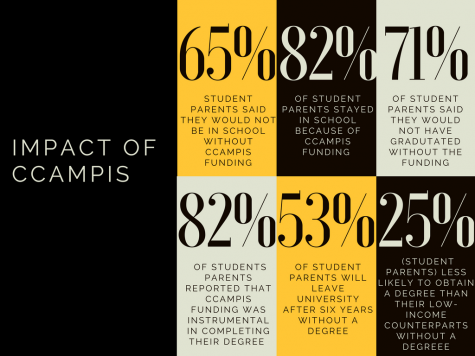

Data from National Coalition for Campus Children’s Centers.

According to an NKU statement, the decision was “not made lightly.” Before the closure, other options were explored, including outsourcing the center.

“The Center has been operating at a significant annual deficit for more than five years, which has required the university to subsidize the Center’s operations by about $1 million during that time,” the statement read. “In today’s fiscal environment, the university is no longer able to continue this significant subsidy.”

The statement also said that the only respondent to the proposal for outsourcing was unable to provide the services needed for NKU to run the center. They withdrew from the process.

“We understand the closure of the ECC will greatly impact the lives of the families and children it serves,” the statement said.

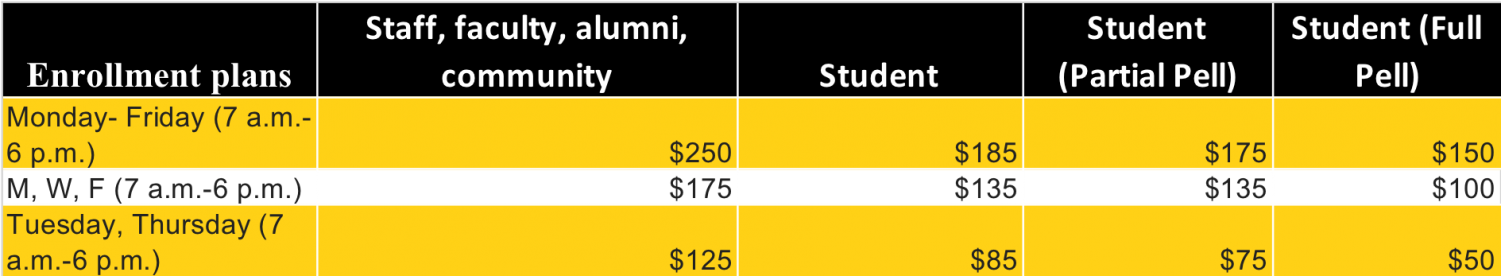

When it closes on June 1, the parents of 50 kids ages 5 and under will have to seek new services. The childcare, in large part, is more affordable than surrounding daycare centers. Many low-income single parents like Hamilton are able to afford childcare through a federal CCAMPIS (Child Care Access Means Parents in School) grant, which NKU received this semester.

Through the U.S. Department of Education, the grant is meant to support low-income parents in postsecondary education in accessing childcare services (recipients must attend school full-time).

According to a study by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR), student parents are more likely to complete higher-ed degrees within six years; only 33 percent receive a degree during that time. On average, low-income families with children under the age of 15 spend 40 percent of their monthly income on child care, while higher-income parents spent between 7-13 percent.

In the state of Kentucky, childcare in a center costs an average of $6,105 annually, according to Child Care Aware of America.

As Hamilton pointed out, the grant has empowered her to go to school so that she can one day be “self-sustainable.”

She paused, laughing as her child reached up for her. She picked up a paper-clipped IWPR packet, pointing out a data from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, which has received the grant funding since 1999.

Between 2005 and 2015, 90 percent of the 123 student beneficiaries of the funding graduated or were currently making progress toward their degrees. 70 percent maintained a GPA over 3.0.

Without the support of on-campus childcare, Hamilton said that more student parents will either have to take time off or not be able to enroll in the first place.

“We’re not just losing the ECC, we’re losing an enriching part of NKU.”ーAlex Voland

Alex Voland, a 25-year-old public relations sophomore, is in a similar situation. Her son started enrollment at the ECC last semester, and the four-star facility was a large component as to why she chose to attend NKU.

“I got out of the Army in 2016 and I was nervous to go to school because I didn’t know what I was going to do half the time because I had a 2-year-old son,” Voland said. “I didn’t think he was ready for daycare, so that’s just a parent’s worry.”

Her son, Elijah, loved it. When she leaves him at the Early Childhood Center she doesn’t have to worry about if he feels happy or safe. Instead, she said she can focus on her classes. The SGA senator (who recently ran alongside Jachelle Sologuren as a vice president candidate) joined because she wanted to make NKU more student-parent friendly. The ‘Save the ECC’ campaign was a significant part of their platform.

Alex Voland and her son, Elijah.

“Elijah, since I was a soldier and deployed when I was very young, already has some issues building trust with adults,” she said. “And so to throw [the closure] on me as the parent two months before it’s supposed to happen–to have to explain it to my 3-year-old in a way that he understands and to let him know he’s losing the people he’s essentially grown up with—it’s terrible.”

“It truly is terrible for both of us. It put us between a rock and a hard place.”

Hamilton felt similarly, but said she won’t give up trying and pushing to keep the the center’s doors open until the last day. Hamilton recently met with Student Affairs vice president Dan Nadler to personally speak with him not only about her feelings, but of statistics stacked against single-parents enrolled in higher-ed. Voland has collected signatures for a petition to reconsider the center’s closure.

“What I hope to do is show the administration, ‘Hey, you guys messed up. People are upset. You hurt NKU students.’ It’s not just, ‘Oh, the budget crisis.’ You hurt your students that you were supposed to protect,” Voland said. “You hurt me, and ultimately you hurt the kids because they’re going to have to go somewhere new. A new environment, a new space, all while I’m still trying to be in college over the summer.”

According to an university statement, to help parents with the transition “the university is looking to secure discounts at other local daycares for them.”

In 2015, former President Geoff Mearns created a task force whose findings said that the the center’s expenses were projected to rise steadily and that the current staffing model would not be financially sustainable.

Despite the task force’s predictions, the university continued to explore options to make the center more financially feasible, according to Amand’s letter.

Like many of her peers, she doesn’t have a reliable form of transportation. With the center, she is able to come to campus, do schoolwork and know her kids are nearby. In response to discussion of finding rates or discounts for NKU students at nearby daycares, Hamilton said it just isn’t a feasible option for those who are single-parents.

“We are low-income parents. We don’t have the means to get to [other childcare facilities],” she said. “Having it here was so crucial and getting rid of it is so detrimental to the chances of anybody graduating.”

Bonds formed outside of the classroom

Samantha Hamilton and her two sons.

Voland said that her and Elijah have formed bonds with several of the workers. Outside of daycare hours, a few of the staff members double as baby-sitters.

“Now Elijah is going to be 10-15 minutes away if I put him in a daycare in Burlington,” Voland said. “I won’t be able to pop in. I won’t be able to take him out to lunch with my friends anymore. It’s going to be a really hard transition for both of us.”

Before daycare, Elijah never took a nap. Becoming emotional, Voland recalled popping in one day just to check-in. Through a two-way mirror (they couldn’t see her), she watched as a teacher held her son. They held him, rocked him and rubbed his hair.

When it comes down to the the center’s value, Voland said she knows that there is a loving adult there.

“When I’m in class, I’m not worried about Elijah being or feeling loved, because that’s all I hear,” she said. When the center closes, she doesn’t know what they’re going to do.

Though Noel Waltz, a journalism major, isn’t a student parent, she says most NKU students know at least one. Also an Student Government Association senator, she said she found out pretty quickly because one of her friends is a student worker.

“I think that everyone should want to be included and be active in the decisions of the university, especially the ones that affect us personally,” said Waltz, who is also a member of the Revolutionary Student Union.

“I have a lot of high hopes, and I’m really determined.”ーSamantha Hamilton

Hamilton wishes students were more included in the conversation. She said she feels like they didn’t give them enough forewarning; she already had summer and fall classes planned, now she has to rearrange everything. So does Voland.

“I’m going to do my best try and keep the center open because I really believe in it and I think that it can change lives,” Hamilton said. “It sounds silly to say that, but a lot of [student parents’] kids won’t get an early childhood education because they don’t have the money. Preschool costs so much money. It’s so expensive.”

Waltz said that students should be able to make decisions and have a say in the university that they pay to go to. Save the ECC’s goal is to form a student coalition in efforts to save the center. An event is in the works, but the date is TBA.

Voland will continue to find signatures–they need 15 percent of the student population to be taken seriously.

“Getting an education, to me, means that I can be self-sustaining,” Hamilton said. “I can take care of myself and take care of my kids and give them a better future. I’m only 25…I have so much opportunity in front of me.”