NKU students protest Sept. 5 DACA decision

Community members gather in downtown Cincinnati to express their disdain

September 6, 2017

“Sí, se puede!” chanted protesters as they stood on the corner of Walnut Street in downtown Cincinnati joined by passersby honking car horns in support of their cause.

“Yes, we can!”

As the Trump Administration announced their formal rescission from the DACA program–implemented by the Obama Administration in June 2012–on Sept. 5 members of Greater Cincinnati and NKU communities gathered in protest of the announcement.

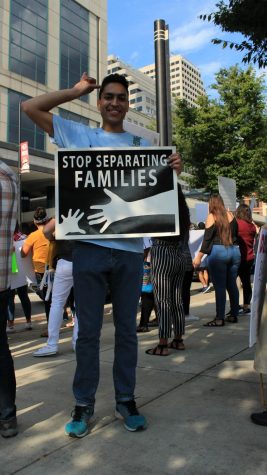

Several NKU students found themselves in the heart of the protest, shouting out in unison with one another and raising signs marked with statements such as, “Education, not deportation,” and “We are all DREAMERS.”

“I came out today because I believe that everybody deserves a chance, and that we’re just as American as everybody else is. And we deserve to be able to work and help the economy, just like everyone else,” Viniza Ramirez, freshman at NKU, said.

DACA, or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, is an American immigration policy which grants undocumented immigrants the opportunity to receive deferred action from deportation for a two year period, which can be renewed. The policy applies to those who entered the country as minors, and helps young students receive educations and careers.

“It’s really a sad day for many Latinos. Particularly those students who are DACA who came when they were maybe two years old,” said Leo Calderon, director of Latino Programs and Services.

“The U.S. promised them a pathway for them to go and be here legally…they [DACA recipients] did everything they could; they met the requirements. And now we’re saying to them, ‘I’m sorry, but guess what? We’re not going to keep our promise.’ It’s one of the saddest days for 800,000 students.”

The estimate for the number of immigrants, otherwise known as “Dreamers,” having received DACA is around 800,000.

Natalia Lerzundi, a sophomore at NKU, and former “Dreamer,” said that DACA is important to her because she is a former recipient, having come to the United States at three years old.

Lerzundi shows her sign in support of the DACA program.

“I was fortunate enough to have someone sponsor my family, and that’s how I was able to get my citizenship,” Lerzundi said. “But unfortunately, not everybody has those opportunities. Not everybody is that fortunate to have someone to give them that opportunity.”

Victor Ponce, who has been in the United States since age five, is a DACA recipient. Ponce said he pictured himself just like any other child going to school, that was until the age of thirteen, when he found out he was undocumented.

“I would sing the pledge of allegiance, I learned the star spangled banner. I learned to love this country. My teacher would always tell us that we could do anything because we were American,” Ponce said. “So that hit me hard when I found out that I was not like any of the other kids.

“What made me different was a piece of paper.”

Ponce took advantage of DACA at age fifteen when the Obama administration passed it. Since then, he said he tried hard in high school and received a 4.9 GPA, as well as scholarships coming into NKU.

“That’s one of the things that DACA allows me to do, it allows me to get an education, a higher education. I would hate to see all my dreams be torn apart if this is taken away,” Ponce said.

According to Ramirez and Jose Sanchez, senior at NKU, DACA recipients must keep a perfect record to continue with the program.

“So many people–especially young students who have no criminal background–came out of the shadows. They gave away their information, so they are open to anything. And they just want to fight for their right to have an education to complete their career goals that they have for them,” Sanchez said.

Sanchez “norses up” to show his dual support for NKU and DACA.

Sanchez said that he was “devastated” when he heard the news of the rescission, but that it only means they have to work harder and continue to push. Calderon said he was also disheartened by the news.

“As a matter of fact, I brought some goodies to the students this morning, because I had a feeling he was going to do exactly that. Our students were totally destroyed. They were crying,” Calderon said.

Ramirez said she was shocked, especially because the program is helpful to the economy, since DACA recipients are required to pay taxes.

“I didn’t think he would actually go through with it. I didn’t think he would actually want something like that revoked, that isn’t harmful to anyone and is beneficial to everyone,” Ramirez said.

Before the program is entirely eliminated, Congress has a six month window to possibly save the policy. For the DACA students, this means their futures depend on that decision.

“For us, this is a scary moment, because it’s our future in the hands of him [Trump] and congress,” Ponce said. “I know we’re fighting for it, but we don’t know what’s going to happen, and for us, that’s very scary.”

For Ramirez and the rest of the DACA students, no one knows now if they’re working for a degree they’ll never use.

“I’m trying to get a degree, and what if I can’t use that degree?” Ramirez said, “Was that four years, five years, just for nothing? Or am I actually going to have a chance to be able to work in a field that I want to work in?”