Your donation will support the student journalists of Northern Kentucky University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

How does the university handle reports of sexual assault?

January 18, 2017

“What do you need?”

Ann James, deputy Title IX coordinator for students, said that’s the first thing she asks students when they report an instance of sexual assault.

“The first thing I do is, ‘What do you need,’” James said. “‘Do you need medical attention, do you need counseling, do you need an advocate? What do you need?’”

Under Obama’s presidency, colleges around the country changed how they handle reports of sexual assault under Title IX, the federal law that protects against sexual violence and harassment.

In 2011, the Obama administration issued a 19-page document, known as the “Dear Colleague Letter,” to colleges across the country, fundamentally changing universities’ involvement in cases of sexual assault. The letter states if a school determines “sexual harassment that creates a hostile environment has occurred,” it must take immediate action to “eliminate the hostile environment.”

NKU’s practices have been under scrutiny amid the ongoing federal lawsuit involving a female student who said NKU mishandled her sexual assault case.

But James said she feels confident the university has the resources to adequately care for survivors of sexual assault.

How are students protected under Title IX?

In addition to her role as Deputy Title IX Coordinator, James also serves as the senior associate Dean of Students and director of Conduct, Rights and Advocacy.

In a broad sense, Title IX protects students from gender-based discrimination, James said.

“Within that umbrella term, gender-based discrimination is sexual assault, sexual violence, dating violence, domestic violence and stalking,” James said.

She said pregnant and parenting students are also protected under Title IX.

“If a student is pregnant, or has recently given birth, or is a spouse or partner of someone who has recently given birth or someone who is pregnant, they’re also protected under Title IX and can’t be penalized for missing work because of that,” James said.

The university conducts an administrative investigation whenever a student reports an act of sexual violence.

James said an administrative investigation consists of mostly information gathering, such as conducting interviews, gathering statements and submitting documentation. A hearing takes place after the internal investigation, and if the suspect is found responsible, the university can move forward with issuing sanctions.

James said it’s important students understand an administrative investigation is not the same thing as filing a police report.

“If the student hasn’t already gone to the police department … we would make sure the student understood how to file a police report because this is not filing a police report,” James said. “This is not a criminal investigation. This has nothing to do with the police at all.”

NKU has three Deputy Title IX Coordinators; in addition to James’ role, Rachel Green, director of employee relations & EEO, serves as Deputy Title IX Coordinator for Faculty and Staff and Leslie Fields, associate athletic director for compliance, serves as a liaison for Title IX in athletics. Kathleen Roberts, senior advisor to the President for inclusive excellence, serves as the Title IX Coordinator for the university,

James explained Roberts is always notified when a report is filed.

“She’s (Roberts) aware of all of the Title IX complaints that are filed, or all of the situations that are going on,” James said. “She doesn’t necessarily do the investigations and things like that, that’s happening at the deputy level, but she’s aware and we run everything through her.”

How are university employees trained to handle reports?

In addition to talking to students and filing reports, James conducts Title IX training sessions with faculty and staff. She also talks to incoming and current students about their rights under the federal regulation.

“Faculty and staff have obligations under Title IX, and it’s important that we all understand — you can’t comply with something you don’t understand,” James said.

James said she trained 322 people in the fall of 2016, which included faculty and staff members and student employees.

She provides in-person trainings to faculty and staff upon request, and she sends emails out to department heads across campus so they know they can schedule a Title IX training session.

In these training sessions, James explains what Title IX, goes over statistics on college campuses related to sexual violence and informs faculty and staff of the resources available on campus. She also explains the obligations of faculty and staff under the regulation, including reporting sexual assault.

James said employees can receive online training through the Human Resources Department.

Martha Biederman, Director of Training & Development for Human Resources, said the department began providing a new online course for all faculty and staff in September 2015. Prior to September 2015, training was offered in specific areas on request.

Biederman said the training session is not mandatory, but that is in line with federal regulations. She said the alteration of training policy would coincide with any change in federal regulation.

In addition to training faculty and staff members, NKU police officers are also trained under the regulation. James said Police Chief John Gaffin has been instrumental in conducting Title IX training for university police officers.

“They’ve been undergoing a lot of training recently on how to help students, how to work with students who experienced sexual violence, being compassionate in addition to upholding the law,” James said. “That’s helped me feel better about working with students. I know that they’re getting good care here, and I can feel very confident in that.”

Chief Gaffin said he tries to make Title IX training for NKU police officers “omnipresent.”

University police officers are trained on a yearly basis, the same as faculty and staff, according to Gaffin.

In addition to this training, police officers review a variety of topics, including Title IX and the Clery Act, which requires universities that participate in federal financial aid programs to record and disclose information on crime that occurs on or near campus.

Gaffin said officers review these topics on a daily basis, often before they even begin their assignments for the day.

“We take 10, 15, 20 minutes, we have different topics that we kind of rotate and then maybe a newly-emerging issue or something that we know about under Clery, Title IX,” Gaffin said. “So they’ll have a powerpoint presentation that’s been prepared, and it’ll have overviews about Title IX, objectives and goals for them like, ‘Define Title IX and the behaviors that it prohibits’ or ‘Who enforces Title IX?’”

Gaffin said posters hang on the walls of the police department to serve as a constant reminder.

“(The posters) just kind of ask officers rhetorical questions like, ‘Are you doing everything you can to prevention violations of this,’” Gaffin said.

Where can students report an instance of sexual assault?

James said the amount of reports have increased in the five years she has served as Deputy Title IX Coordinator for students.

“It’s increased, not because our incidents are increasing, but because we as a university are doing a better job informing students how to report and what their resources are,” James said.

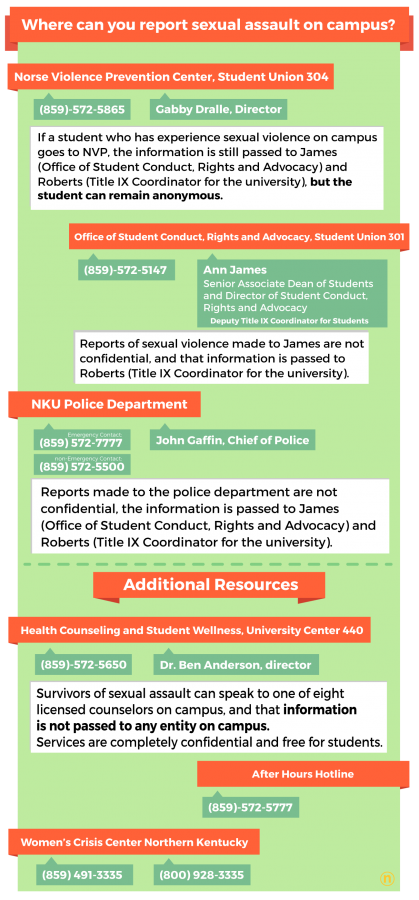

One of those resources is the Norse Violence Prevention Center (NVP), an on-campus advocacy center that aims to provide support to survivors of sexual assault.

In addition to the services NVP provides, Gabby Dralle, director of the Norse Violence Prevention Center, said they can direct students to other resources in the community as well as on campus.

Dralle explained NVP’s mission in a September interview with The Northerner.

“We’ve helped students file police reports, get protective orders, we will go to court with students, so if there are criminal charges, we accompany some students to court… anything a survivor may need as a student but also as a survivor,” Dralle said.

For this reason, James said students often report sexual assault to the Norse Violence Prevention Center.

James said reports made to NVP are reported back to her so she can include them in the university’s Clery report. (The Clery Act dictates that universities must record all campus crimes and crimes adjacent to campus in a Daily Crime Log and Annual Security Report.)

“If we get a report, and when I say we, I mean anybody at the university really except for medical professionals, we give those numbers to university police so that our Clery report is accurate,” James said.

This includes situations where a student does not want to give their name when they report to NVP. James said that report is still passed on to her anonymously.

She said some students go to NVP, and they don’t go anywhere else (Office of Student Conduct, police department) because they may not want to file a report at the time.

“If they’re getting what they need — support and help — by not coming in here and making a report, that’s okay,” James said. “I would obviously prefer that they did, because that’s us getting a better idea of what’s going on and being able to address it.”

She said there are also options for students who want to speak about their experiences confidentially. Students can talk to licensed counselors within Health, Counseling and Student Wellness on campus, or they can talk to an advocate through the Norse Violence Prevention Center.

Students can also anonymously speak with someone 24 hours a day, seven days a week. NKU has an on-call counselor after hours for students who have experienced a crisis.

James said after hours students can also call the Women’s Crisis Center Northern Kentucky , a nonprofit based out of Covington, dedicated to ending domestic violence, sexual assault and rape.

“Any student can call that, that is a 24-hour, on-call service for students who experience any kind of power-based personal violence,” James said.

How is the NKU Police Department involved?

Gaffin said the department is aware of all reports made through the Norse Violence Prevention Center and the Office of Student Conduct, but they don’t act on those reports unless there is a present threat to the campus community or if the victim chooses to file a police report.

“The survivor at that point has a right to their privacy … they (NVP or Office of Student Conduct) can’t come and tell us necessarily the name of that person or where it happened. The person gets to do that,” Gaffin said. “It’s not their place to step over that person’s privacy, but we do find out about the incident. We find out the details of generally where and generally what happened.”

If the incident seems like a threat to campus, Gaffin said the police department will issue a timely warning email. The NKU Police Department issued a timely warning after a student said she was raped in her dorm room in October.

“The first thing we do is make sure that everyone is safe … and that everyone’s needs are met,” Gaffin said. “If that means that we need to get them to the hospital right away, we’ll do all of that before the investigative piece starts.”

Gaffin said whether an investigation takes place depends on the person’s readiness.

“One of our chief goals is always to connect the person will all the resources that are here on campus,” Gaffin said. “So that can impact our next steps too because they may want an advocate present when they’re interviewed. They may want some of those resources before we start talking about it.”

He said it’s important to understand the reporting process and the prosecution process are distinct.

“So you can report to us, we can get this documented, we can get this on record, and then if you elect that you’d rather not go into a courtroom and tell your story, you’d rather not pursue an outcome through the justice system, then you don’t have to. That remains entirely your decision,” Gaffin said.

He said students should be able to separate those processes and understand they can go forward with a university administrative hearing, or they can go through the court system. Survivors could even move forward with both of those processes if they choose.

“There’s two distinct processes in seeking some kind of sanction, some kind of action against the alleged perpetrator, and that’s to go through the university’s internal disciplinary process and then to make a report to the police and go through the court system… there’s different nuances and different burdens of proof with each processes,” Gaffin said.

When dealing with sexual assault cases, Gaffin said it can be difficult to realize that prosecution doesn’t always solve everything.

“The thing that is hardest sometimes for officers to separate from this is to realize that the process of making that survivor whole again doesn’t always involve prosecution, and going into the courtroom, and telling the story. Because that can be very traumatic and kind of re-victimizing in a lot of ways,” Gaffin said. “So there’s a of times that that’s not the route that people (survivors) want to go.”

Despite the difficulties, Gaffin thinks the way society views survivors is changing for the better.

“I think what we’ve really seen big picture is a shift toward a process that is oriented around the survivor,” Gaffin said. “Hypothetically, if a survivor pursues an outcome through the court system, and the person is convicted and spends time in prison, that’s perhaps a positive outcome, but it doesn’t mean a lot if that person wasn’t connected with resources and they’re still struggling internally.

“I think that’s really why we’ve seen this transition towards getting these folks plugged in with resources and helping them, and then moving forward with some of the other processes.”

James agrees her primary focus is for students who have experienced sexual violence to feel comfortable enough to talk about it.

“The more students who are sharing with us, the more the university can take steps to make sure that we’re doing what we need to be doing — so number one, prevent these things from happening, and number two, addressing them when they do happen.

“Whatever a student wants to do, my goal is that students know what their options are and that they have access to all of those options. That’s my priority.”