Your donation will support the student journalists of Northern Kentucky University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

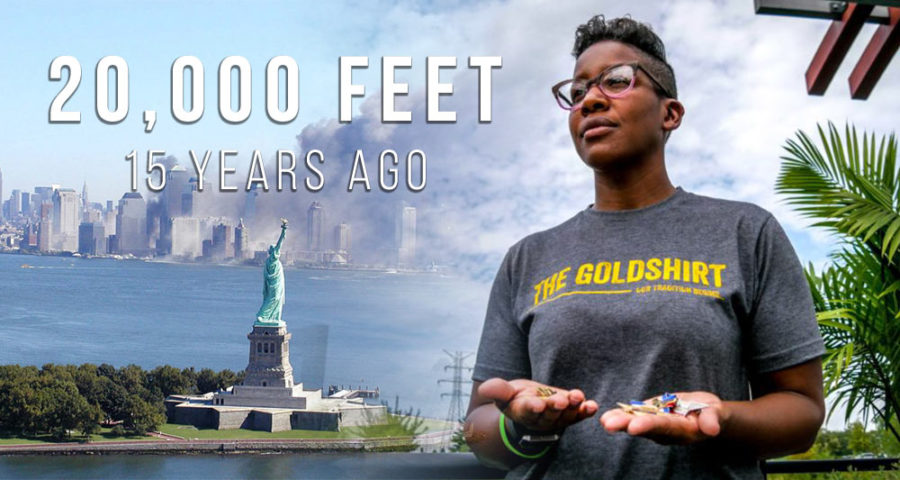

How a former flight attendant rose above the 9/11 attacks

September 11, 2016

Fifteen years ago, Shanda Harris’ family didn’t know if she was dead or alive.

The then 27-year-old flight attendant was 20,000 feet in the air, working a Comair flight from Cincinnati to Charlotte, when an airplane smashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center.

With her back to the 30 passengers onboard, Harris took a phone call from a crew member.

The now 42-year-old NKU student recalls what she heard through the phone.

‘Shanda, we need to land immediately, or we’re going to be shot out of the sky.’

Her 11-year-old daughter, Kayla, flashed in her mind. She felt sick to her stomach as she thought about her family and the families of the 30 souls on board the aircraft.

“Nerves set in… but you can’t panic,” Harris said. “You have to maintain control, your facial expressions,

(From left to right) Niki Ross, Lori Hawkins-Gunn and Shanda Harris pose for a picture before working a Comair flight. Harris said she met some of her best friends while flying.

everything — all of your actions.”

At the time, Harris had no idea what had happened thousands of miles away at the World Trade Center. All she knew was she to act quickly.

“I had to get myself together, turn around, and make up something to tell the people why we were going to have to land immediately without inciting panic,” Harris said.

Back in her hometown of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, her daughter was called into the principal’s office. Harris’ aunt sat with Kayla and told her about the multiple planes that had crashed that morning.

She told the little girl they weren’t sure where her mother was, and all they could do was wait for a phone call.

But Harris wouldn’t be able to call her family for hours.

The only flight attendant aboard the aircraft that day, she had switched into emergency mode.

She told her passengers they had to do an emergency landing due to a minor mechanical issue, and once it was resolved they would continue the flight to Charlotte — but Harris knew the plane would never make it to North Carolina.

The aircraft landed at Tri-Cities Regional Airport, a small airport in Blountville, Tennessee. She was instructed to open the door and get all of the passengers off the plane and inside, but first she connected with her crew who had called the control tower.

They told her two planes had crashed into the World Trade Center, and another plane had went down in a field in Pennsylvania.

“At that point, I looked at my cabin of passengers that I had, about 20 to 30… and it became kind of a blur,” Harris said. “You’re just worried and concerned with getting your passengers inside, getting these people to where they need to go and safely.”

Harris did just that. Once she moved all of her passengers inside, she finally called her family to let them know she was okay.

“When I called my mother at work, she started to cry,” Harris said. “I kind of get emotional about it, because she didn’t know if I was dead or alive.

“She knew I was a flight attendant, she knew that I was going on a trip, and I was ultimately supposed to end up in New York that evening… which I never did.”

Shanda Harris displays her flight attendant pins in the palms of her hands. She was working a flight to North Carolina the day of the 9/11 attacks.

Harris was stranded in a hotel in Tennessee for four days with hundreds of other crew members from different airlines across the country. The small airport where her plane had landed was not a top priority to be reopened.

Local businesses brought food and grilled out, and they donated different items and necessities to the crew members.

“We kind of became a family, we had to survive, but again we had to think about our families,” Harris said.

Once Tri-Cities Regional Airport reopened, Harris was told she had to work a flight back to Cincinnati. With passengers.

“The anxiety level was really high, because here I am being told, ‘Now you have to get on a plane, and you have to get this plane back to Cincinnati. But not only that, you have to carry people,’” Harris said. “I don’t care what anyone says, this is my personal story, I profiled every single person who came on board my aircraft. It didn’t matter what nationality you were, it didn’t matter where you were from in the world, it didn’t matter to me.

“At that point, I was more concerned with safety and getting back to Cincinnati to see my family.”

Shanda Harris, now a 42-year-old sports business major, said the 9/11 attacks forever changed the way she felt about flying.

Harris made it home to her family, and she continued working for Comair for 11 years following the 9/11 attacks. However, her career never felt the same.

“Before 9/11 it was fun. I started out in the industry when my company was booming, so we were flying everywhere… once 9/11 happened, the whole dynamic changed,” Harris said.

“Me as a flight attendant, and even just crew members in general, we were harshly scrutinized coming through the airport. Going through security, there were things that we were used to that were taken away.

“There were times when I would have to go on a five day trip, and they didn’t want me to bring a certain amount of liquids, they didn’t want me to bring certain things in my bag, things that I had carried all the time.”

In addition to the high pressure on the plane, Harris said the security measures inside the airport were also difficult to adjust to.

“When you were going through security and bells and whistles are going, TSA is pulling you over and they’re wanding you in front of passengers who already don’t have this trust with crew members. So now you’re sitting there, and you’ve gotta prove not only to the FAA that you’re okay to go, but now as passengers board the plane, you have to show them that they can trust me to get them from point A to point B safely,” Harris said.

When Comair closed in 2012, Harris decided to turn in her wings as well.

“I know that this tragedy changed the lives of many of my coworkers and my family,” Harris said. “Ultimately when my company closed, the first question my family asked me was, ‘Are you going to fly again?’

“I thought about it, but my mother and my father and my daughter were sitting there, and they said, ‘We would really appreciate it if you did not fly again.’ I didn’t realize the stress that I put on my family by being a flight attendant.”

Harris wore this 9/11 pin everyday following the attacks to honor those who lost their lives that day.

She came to NKU for a new start, hopeful about pursuing a second career in something else she loved.

The now sports business major and president of the Economics Club is set to graduate in the Fall of 2017, and she is excited about starting a new career in the sports industry.

Although she has found a new passion, Harris said she will never forget about her time as a flight attendant or what happened on U.S. soil 15 years ago, but she has no desire to fly again.

“I don’t miss flying. I can say that I miss it sometimes, but not for the work aspect,” Harris said. “I miss flying for my leisure travel, for the crew members that I flew with, for the family that I had when I was flying. My co-workers were awesome, and I loved flying with them.

“But it’s not something I would ever go back to doing. Ever.”