African-American students feel lost in the crowd

Members of the Black United Students organization at NKU pose on campus. Some members of this organization have recently voiced their concerns with the treatment of African-Americans within the university.

Shirby Ferguson describes the demographics of the NKU community as “like peppered grits.”

Ferguson, a junior public relations major and president of the Black United Students organization at NKU, says the university has made progress in the number of African-American students on campus, but there is still a very long way to go.

“You have a big bowl of white grits and you sprinkle some pepper on them, but once you stir up the grits, the pepper tends to disappear, and you see it periodically as you dip your spoon in the bowl, but it gets overlooked. And I feel like as African-American students on this campus, we get overlooked.”

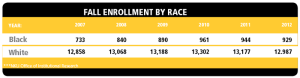

And while this “progress” she references has been made in terms of quantitatively increasing the African-American student population, Ferguson’s allusion to NKU remaining a predominantly white campus is accurate.

As of Fall 2012, 87.6 percent of NKU’s student population was white, compared with the 6.3 percent population of African-American students.

“There is just no understanding,” she said. “When I get up in the morning, I know I’m coming to a white campus. I know I might not get rewarded all the privileges… I don’t get looked at the same.”

The solution to this problem, according to Ferguson and fellow sociology major Brandi Estrada, is to recognize race as an issue, so it can be discussed and dealt with.

“If you don’t see color, you don’t see me,” Ferguson said referring to her status as an African-American student. “When we begin to acknowledge race as an issue, we can deal with the problem.”

Estrada said she looks to NKU as an institution to properly address these issues and represent the African-American population.

“A neutral mindset for our institution is not enough,” Estrada said. “We need continued help and resources for this population.”

“A neutral mindset for our institution is not enough,” Estrada said. “We need continued help and resources for this population.”

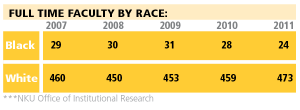

Ferguson recognized hiring more African-American faculty as a place to start.

“There’s no sense of familiarity,” she said. “Nothing looks like us.”

As of 2011, there were 24 full-time African-American faculty and 473 full-time white faculty. Compare this to 2007, when there were 29 full-time African-American faculty and 460 white full-time faculty, you see a slightly decreasing African-American full-time faculty member population and an increasing white full-time faculty member population.

Ferguson said this trend leaves a lack of familiarity in the classroom and surrounding environment and can lend a degree of resentment from African-American students toward the institution.

“You really begin to resent the school,” she said. “ And a school is nothing without the people in it.”

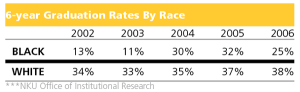

Ferguson suggested that this could be a cause of issues such as lower graduation and retention rates for the African-American students at NKU.

From the fall 2006 freshmen class, African-American students have a 13 percent lower six-year graduation rate compared with the white population, according to data from the NKU Office of Institutional Research.

NKU’s demographic history

From 1980 to December 2008, NKU was under a desegregation plan after it was out of compliance with the Civil Rights Act.

Other universities within the state were also put under this plan which “aimed to address the grievances or the concerns of African-Americans,” according to Chair of the Department of Social Work Willie Elliot, who has served in the role of special adviser for campus diversity for the past five-and-a-half years.

“In 2008 we were released from that [desegregation] plan with the caveat that we would develop a statewide diversity plan,” Elliott said.

Since then, the university has adopted a new Campus Diversity Plan. This plan was devised after surveys were sent across campus to receive input and feedback from 16 focus groups, according to Elliott.

The main goals of that plan were to establish a new full-time position to deal with diversity issues and to focus on demographics around African-Americans and Latinos.

The next step would be another round of campus surveys to develop a new plan for the next five years, according to Elliott.

“So we’ve gone through the desegregation plan, we’ve been under a diversity plan and now we are moving more toward inclusiveness. And, inclusiveness is the broadest range of diversity.”

Moving forward

Elliott said that he would like to see more African-American students, faculty, staff and administrators.

As shown, NKU has made progress in increasing the number of African-American students; between 2007 and 2012 there was a 26.7 percent increase in enrollment.

“NKU has changed in that it’s much more accepting,” Elliott said. “I came in 1989 and the biggest change I see is that Northern is more reflective and more acceptive of difference. In our society, difference is equal to deviance and that’s the fear.”

Earlier this month, NKU President Geoffrey Mearns announced that he will establish the new position of senior adviser to the president for inclusive excellence.

Mearns said he plans to create a search committee over the next few weeks and anticipates having an adviser selected by April or May.

But is all this enough?

Some African-American students and faculty believe there should be more of an emphasis on black studies in the curriculum.

“The only thing to help this is to kill ignorance with knowledge,” Ferguson, the Black United Students president, said. “And that’s why programs like black studies are important.”

Courses in the black studies minor offered at NKU are designed “to provide students with an interdisciplinary perspective of the life of African-Americans, including Africans and African people through… their contributions to humanity.”

Professor Michael Washington teaches classes for the black studies minor and believes that all students across campus should be required to take at least one of these courses.

These black studies courses were part of the old general education requirements before the university switched its programs in Fall 2010, Washington said.

“The black studies courses are important because all people need to be aware of these issues and have training to deal with these issues in black culture,” Washington said.

Several students rallied together earlier this semester at a strategic planning open forum to “save black studies” and raise awareness for these courses and the benefits they could have on NKU.

Along with classes such as those offered in the black studies minor, there are other resources offered specifically for African-American students.

Ferguson’s organization, Black United Students, looks to foster the development of African-American students along with other places on campus such as African-American Programs and Services.

“The campus must be culturally validating to all students,” Elliott said. “We need African-American student affairs, black studies, so that when African-American students come, they can gravitate toward that, but in a year or two they need to then move out to the larger campus.”

Overall, Ferguson seemed optimistic about the idea of inclusion, but admitted the American idea of a melting pot doesn’t always work.

“If you melt together and lose a sense where you came from, you tend to lose who you are.”