WASHINGTON – A teenager’s senseless death on a Florida interstate nine years ago sparked driver’s license changes nationwide that are saving hundreds of young people’s lives and averting thousands of crashes.

The new approach makes teens wait longer to obtain unrestricted licenses and requires more adult supervision of novice drivers. It also keeps young passengers out of the cars of teens who are learning to drive and reduces night driving.

The changes “always made a lot of sense,” said Allan Williams, the chief scientist at the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety in Arlington, Va., a research and communications group. But state lawmakers rejected them as unfair for years. As the Los Angeles Times put it in a 1983 editorial, “It is contrary to the nature of teenagers to be home from a date by midnight.”

So until Tiffany Accardi, 16, of DeBary, Fla., plowed the 1992 Pontiac Sunbird her father had bought her into an oncoming Honda sedan on I-95 near Titusville on Labor Day 1995, state lawmakers ignored some hair-raising findings about young drivers.

Among them:

* Drivers ages 16 and 17 have the highest crash rate per mile of any age group. Their risk is nearly three times that for drivers 18 and 19.

* Newly licensed drivers have more than double the crash risk that they’ll have after they’ve been driving for six months.

* The crash risk at night is three times the daytime risk for 16- and 17-year-olds.

* The crash risk soars when 16- and 17-year-old drivers ride with unsupervised teen passengers. With three passengers, for example, the crash risk quintuples compared with when teens drive alone.

The odds haven’t changed much. Lawmakers in New Zealand in 1987 and then in Australia and Canada found ways to keep young drivers out of high-risk situations. They relied on U.S. teen-driving research that’s been around since the 1970s.

Since 1996, when Florida toughened its standards, all but three U.S. states – Kansas, Montana and Wyoming – have imposed new limits, which are lifted in stages as drivers gain experience.

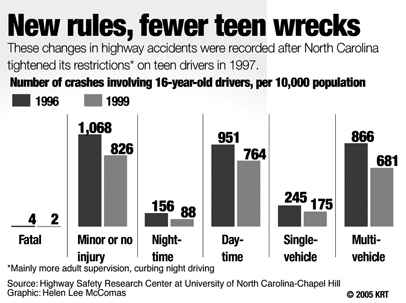

Nationwide, the tougher laws are producing heartening numbers: Fatalities and injury-causing wrecks fell 32 percent among Michigan’s youngest drivers, compared with the years before the new restrictions were in effect. North Carolina’s fell 28 percent, Ohio’s 24 percent, California’s 17 percent and Florida’s 11 percent.

Outcomes vary from state to state largely because their laws vary. But it’s clear that the tougher the rule, the more lives saved. North Carolina, which bars unsupervised driving after 9 p.m. for initial and intermediate permit-holders – most of them 16 – cut their night crashes nearly in half. Florida’s curbs, which kick in at 11 p.m. for 16-year-olds and 1 a.m. for 17-year-olds, cut their night crashes 17 percent.

Compliance remains a concern, however, especially for young male drivers. Police rarely enforce the new curbs except when they’re incidental to accidents or other violations.

How many lives are being saved can only be estimated, because most states haven’t figured it out. California’s 1999 restrictions averted roughly 400 fatal or severe-injury crashes in the next two years, according to one study. Ohio saved some 30 lives a year, according to another study. Michigan averted roughly 2,000 fatal and nonfatal injury crashes a year among 16-year-olds, according to a third.

Williams, of the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, put the number of lives saved to date at something like 1,000; crashes with injuries, in the tens of thousands.

He and other experts can’t explain, however, why Florida’s lawmakers, who’d rejected tougher licensing three times, suddenly got behind what Williams calls “one of the strongest public health movements ever seen in North America.”

Williams even wrote a paper about this “mystery.” There was no change in the size of the problem, he noted, and no research breakthrough. There were no federal sticks or carrots, not even any big parental organizations such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving, to push it.

The catalyst was Florida teen Tiffany Accardi, who’d earned an A in driver’s education at Deltona High School. She’d gotten her license “driving around a buncha cones in a parking lot,” as her aunt, Diane Zeidwig of Deland, Fla., put it.

Accardi, with two months of licensed driving experience, had three teen passengers with her in the Sunbird on I-95. She’d fought with her boyfriend, according to Zeidwig, and witnesses estimated that she was driving 90 mph or more when she crossed the interstate’s median strip.

The crash killed five: three teens – Tiffany and two of her passengers – plus a father from Miami in the other car and his son, age 4.

Zeidwig and Accardi’s parents moved quickly. Amid intense statewide news coverage of the carnage, they persuaded a state legislator, Republican Rep. Earl Ziebarth, to back a license-toughening bill.

Despite the American Civil Liberties Union’s threat of a lawsuit (“The government has no right telling people they can’t be in a car after a given hour,” its statement said), and the indifference of then-Gov. Lawton Chiles, whose mail ran 15 to 1 against passage, lawmakers approved the Accardi family’s measure.

It passed by voice vote at 1:52 a.m. on May 4, 1996, eight minutes before the 60-day legislative session ended.

Terry Moore, Ziebarth’s legislative aide at that time, recalled that Lt. Gov. Toni Jennings of Orlando, then the chairwoman of the Florida Senate Rules Committee, included the measure in a package of quickly approved final-hour bills as a tribute to Republican state Sen. Malcolm Beard, the retiring chairman of the Transportation Committee.

After Florida acted, four other states followed that year, eight in 1997, 12 in 1998, 11 in 1999 and so on.

According to David Preusser, the president of PRG Inc. of Trumbull, Conn., a leading teen driver-safety consultant, “It was like a dam had broken.”

Tiffany’s father, Roger Accardi, 59, a pharmacist, and his sister Zeidwig, a marriage and family therapist, share a theory about why the dam broke.

Before telling her version of it, Zeidwig, who holds a master’s degree in counseling, described herself as “a very practical person” and “not a devout Catholic, though I go to church.” She said she hadn’t had paranormal experiences before or after the one she was about to describe.

Zeidwig said she was sitting on her brother’s couch, both of them in tears, depressed and sliding into deeper depression, on the afternoon after Tiffany’s death.

Suddenly, “a bolt of light came out of the fireplace and hit me in the chest,” Zeidwig said.

“I jumped up and said, ‘We’ve got to do something!'”

Zeidwig’s brother doesn’t recall seeing the light, but Roger Accardi said “something jolted her” and that their license-toughening campaign was born in that moment.

Accardi and his sister, who didn’t participate in other states’ campaigns, were surprised to find the Florida drive so effortless. `People were coming to us to ask what they could do,” Zeidwig said. “It just rolled.”

Accardi’s theory about the effortless campaign is this: “It was to a large degree orchestrated by my daughter.”

Zeidwig agrees. Tiffany had been an animal rights activist, a human rights activist and an environmentalist, she said. Saving young drivers’ lives would have been in Tiffany’s line of work.

“I felt like Tiffany was running the show and telling me what to do,” Zeidwig said.