Your donation will support the student journalists of Northern Kentucky University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

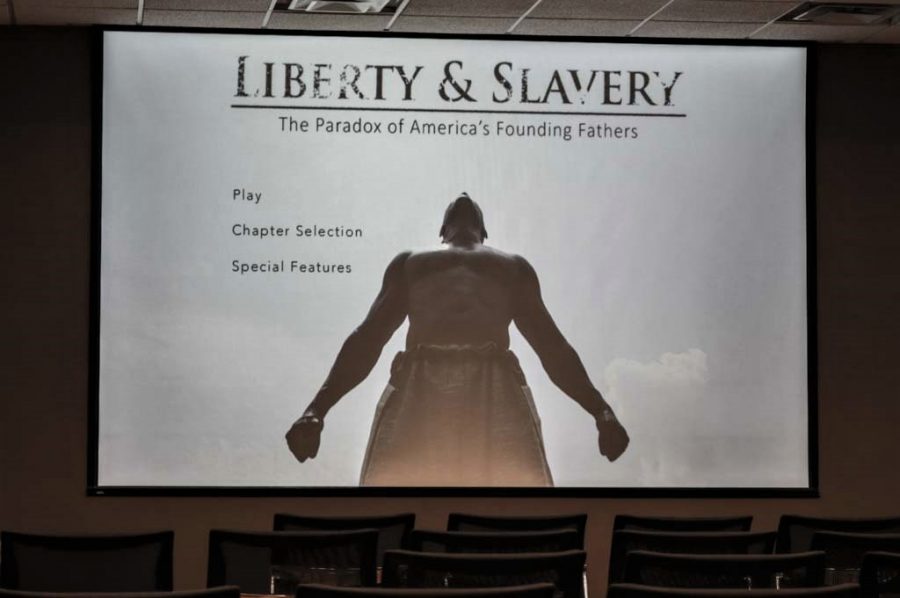

The award-winning documentary “Liberty and Slavery: The Paradox of America’s Founding Fathers” was shown at NKU on Sept. 28.

Slavery and Freedom: the American Paradox

October 7, 2017

After the on-campus screening of award-winning documentary “Liberty and Slavery: The Paradox of America’s Founding Fathers” and a 20-minute promo for the unreleased film “All or Nothin'” on Sept. 28, a panel discussion that included both the creators and professors followed.

The panel discussion included writer, director, and executive producer A. Troy Thomas (“Liberty & Slavery: The Paradox of America’s Founding Fathers”) and director, Charles K. Campbell (All or Nothin’). Professors Brian Hackett, Debra Meyers, (History) and Kristine Yohe (English/ African American Literature) accompanied Dr. Eric Jackson, another NKU history professor featured in the documentary as a professional source.

This event was sponsored by the College of Arts & Sciences, the Department History & Geography and the Black Studies Program, Steely Library and the Office for Inclusive Excellence.

“How could our founding fathers fight for liberty and at the same time own slaves?” asked Thomas.

“The founders are greatly revered: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, James Madison. I never heard any of the slavery part when I was growing up in middle school and high school. As I got older, it bothered me that I never heard that part.”

After years of observation, Thomas said he chose to pursue questions he had formulated in the form of filmmaking.

“It really struck me that here you had these men who were fighting for liberty and yet many of them owned slaves,” Thomas said. “How do you make sense of that? How do you reconcile those two things? It was a paradox, but nevertheless, it’s true.”

Aiming to answer this enigma, Thomas reached out to experts across the United States four years ago in search of a more comprehensive understanding. One of the institutions he contacted was the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center located in Cincinnati. From there, Thomas was directed to Dr. Eric Jackson.

In the film, Jackson and an array of other professionals facilitated the discussion in regard to America’s founding fathers’ relationship with the fundamentals of freedom and the implication of slavery. Critical questions were asked throughout, such as “What were our founding fathers’ views on slavery?”, “In what ways did they protect the institution of slavery?”, and “Why was the process of abolishing slavery incredibly complex?”

“They started the conversation about liberty, equality, justice and freedom; they didn’t end the conversation,” Jackson said

Hackett emphasized why this topic is relevant today.

“People have to be able to relate history to their own lives, and there’s no time like the present. You see things that are going on in the NFL, in Black Lives Matter, and other things; this is showing the roots of that. I’m a great believer in that America is in a constant state of becoming and that we are always getting better,” Hackett said.

Hackett went on to quote Winston Churchill who once optimistically said, “America always gets it right, but not right away.”

Educational films like “Liberty and Slavery” are vital to understanding the interdependent relationship history has with the present. The more information we acquire, the better we can analyze events surrounding us.

Audience members had the opportunity to ask the panel questions after the showing.

“I think it’s really important because a lot of the race relations we have going on in America today, a lot of it goes back to this. This is where some of the anger started,” Thomas said. “I don’t think a lot of people clearly understand where slaves came from, when they came over, how long they’ve been here. I wanted them to understand that.”

One of the major outcomes Thomas wanted from this documentary is the implication and impact of racial reconciliation in a way that Americans can conceptualize these broad topics.

“I don’t want people to say ‘Oh, that happened hundreds of years ago–that’s not relevant,’” Thomas said.

Like the nation’s founding fathers discovered, the solution is not transparent. The film leaves the viewer with open-ended questions to reflect on such as what liberty is, how individuals approach the concept of freedom, and if it’s relative or universal.

“It’s a complex response. As a man of faith, I think the issue is you have to articulate hope,” Jackson said. “You have to give people hope regardless of your discipline. I have to figure out how to use the film to articulate the aspect of understanding how to move forward in a world that’s confusing to a lot of people.”

The film uncovered a hopeful reconciliation: that many of the country’s founding fathers did not condone slavery, especially after the Revolutionary War. In subtle ways, they set the stage for future leaders to initiate abolition. For example, creators of the Declaration of Independence purposely chose to change John Locke’s idea of “Life, liberty, and property” to “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” hoping that one day enslaved men and women would no longer be viewed as property.

Dr. Jackson used the words of Martin Luther King, Jr. in his concluding thoughts quoting, “We will come together as brothers and sisters, or we will die as fools.”