“Black Boy In Pink” deals with sexuality, race

One of three Y.E.S. Fest 2019 plays, 'The Black Boy in Pink' opens Friday

April 3, 2019

An eleven-year-old Isaiah Reaves made one wrong click and 160 pages of his document disappeared. Reaves laid at the foot of his mom’s bed and cried.

The first play he had ever written was gone, and he didn’t know how to get it back.

The next day, he began again and continued with his stage adaptation of “The Diary of Anne Frank,” unaware that one already existed. It was then that he realized he loved playwriting.

At age 14, Reaves wrote a play titled “Wyatt’s Bed” about “straight, White, rich people in New York.” It featured a prostitute and a pimp, and the plot didn’t make much sense. He performed it when he was 16, self-produced it with some friends from high school and organized a reading at Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park.

“I put the play down because I grew from that and it’s just not a good play,” Reaves said.

Reaves cites Anne Frank, playwright Tennessee Williams and his grandmother as inspirations. He continued writing other plays, incorporating elements from his personal life and his family history.

“Wyatt’s Bed” would eventually be revisited. During the summer of 2018, while working on his production of “The Blackface Project” (named CityBeat’s Fringe 2018 critic’s pick) at the Cincinnati Fringe Festival, Reaves experienced personal turmoil that resulted in many aspects of his life collapsing.

After Reaves returned to NKU, Director Brian Robertson approached him about the Y.E.S. Festival potentially including a student work. Reaves was asked if he’d want to bring back “The Blackface Project” or do something different.

“There were just some things that I needed to purge and explore,” Reaves said.

Things he had internalized about parents, his grandmother, different men came pouring out, joined with his conflicting emotions about his home—Cincinnati.

“Wyatt’s Bed” became “The Black Boy in Pink”—inspired by his several interactions that he had with men this past summer. He said those interactions “sort of made me feel like a prostitute.” His main character—a straight, White woman in New York City, became Wyatt—a gay, Black man in Cincinnati in 1959.

“From 1959, when this takes place, to now, it’s surprising how little has actually changed,” Reaves said.

“The Black Boy in Pink” has some autobiographical elements, but it follows Reaves’ habit of sticking to fiction. Reaves incorporated research, aspects of himself and other people he’s encountered into each character in this show, but no character is wholly Reaves. Wyatt is more a surrogate of himself than a self-portrayal.

Reaves graduated from a Cincinnati all-boys Catholic school, which he references in his show. He said that Cincinnati is a city in conflict with itself filled with tragedy and pathos and many people are unaware of the rich and diverse history of the city and his community within the city.

He said there’s an undercurrent of racial tension and homophobia that has always been present in the city.

These many contradictory characteristics of Cincinnati interested Reaves enough to base all of his plays here for the time being.

While researching for the show, Reaves had to rely on the internet, Facebook groups about historic Cincinnati and his own projections of what it might have been like to exist as a gay, Black man in 1959.

Reaves said after reviewing these resources, as well as doing some of his own research amongst his peers, he couldn’t find in-depth reports on the life of a gay person pre-1970, regardless of race.

He wanted to write about gay and black communities, and their intersection, to prove that they have always existed, even when they weren’t vocal or in a position to be able to freely express who they were. Some people of color in his community won’t validate his existence, which Reaves said can be attributed to factors like religion and the remnants of white supremacy.

“We are erased,” Reaves said.

By putting his story out there through his characters, Reaves continues to speak his truth through theatre, even if people don’t like it. He’s going to continue to “discover and reinvent” himself and strive for honesty in all aspects of his life, including his writing. To Reaves, theatre is an experience like church is for others—it’s spiritual and intimate.

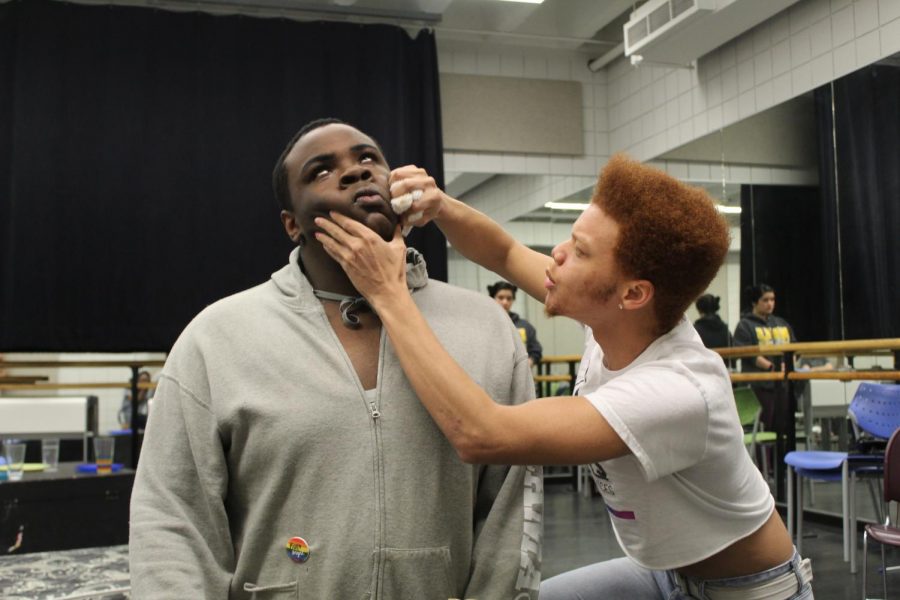

Reaves has been an inspiration for lead Jeshaun Jackson throughout the process. Jackson said he has faced people telling him, “You’re not going to get in anything. You’re Black. Get over it.” To see a person of color have their work, called “The Black Boy In Pink,” chosen and treated as a mainstage has been inspiring for him.

Jackson said predominantly Black shows are slim to none but that people of color are beginning to be recognized as actors, too.

“We’re all equal, too; we all have the same amount of talent. We all work just as hard. It doesn’t matter about skin color,” Jackson said.

Jackson said he has questioned the motive behind some of his castings, wondering if he was chosen because of his race or his talent. He wondered if he’d be accepted at NKU as a Black person, but after being involved in the theatre department, Jackson said he looks at it differently.

“They nourish you on your talent,” Jackson said.

Jackson felt connected to Wyatt, relating to the character searching for his place and for validity from other people. But, after learning Reaves’ vision for the show, Jackson felt even more connected.

“Just watching [Reaves’] face and seeing him relive every moment—that’s kind of intimidating,” Jackson said. “Are we telling the moments just like how he planned?”

Yet, Reaves comes up every night to tell the cast thank you for telling his story. He validates them and reassures them that they’re “heading in the right path.”

But the process has been emotionally draining. At one point, Jackson caught himself crying during a scene that wasn’t even supposed to be sad. But his emotions peaked and he said, “Wow. This is magical.”

Jackson says the show is phenomenal, and it’s a necessary story for people to hear.

Reaves primarily wants people to react, whether that be positively or negatively. His ambition isn’t to change people through his play, but to make a statement through putting gay and Black lives on the stage unapologetically.

People have chosen to ignore these identities for so long that Reaves wants the audience to be able to watch his show and soak in his truth, although he’s nervous about how his family will react.

“There’s such abundant sexuality in it. We’re honest and we’re raw and we’re having a dialogue and it’s real,” Reaves said.

People will be faced with realities they may be uncomfortable with. But Reaves said he believes “theatre should scare us.”

Wyatt’s story tells the story of Reaves, of Jackson, of the identities that have been erased in history. It’s the story of looking for your place, standing up for yourself and not being afraid of who you are.

“I don’t think everybody is going to like this play,” Reaves said. “It explores sexuality and race and it’s gritty and it’s very uncompromising.”

“The Black Boy in Pink” is free to attend, but reservations must be made at NKU’s box office on the first floor of SOTA due to seating restrictions. The show runs from April 5 through 14. Showtimes can be found here on NKU’s website.