Your donation will support the student journalists of Northern Kentucky University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Students and faculty use 3D printing to ‘Build a Better Book’

February 21, 2023

For English professor Dr. Tamara O’Callaghan, finding a way to intersect the humanities with cutting-edge technology holds potential far beyond simply helping English majors acquire multidisciplinary skills.

Makerspaces furnished with 3D scanners, 3D printers and laser cutters for people to experiment and research with are popping up in libraries around the country, including at the Steely Library with Stego Studio.

But how could an English professor design and offer a course that uses 3D printing to enrich understanding of language? Well, one answer is to use it to make language more accessible for others.

The Build a Better Book program started in Colorado and encourages middle schoolers to engage with makerspaces by having them develop physical objects to pair with storybooks to make reading more immersive for children with visual impairments. When O’Callaghan was alerted to the program, she was instantly intrigued. So, she reached out to the program to explore how she could translate this program to a university classroom.

A crux of the Build a Better Book program in Colorado is its potential to stimulate tangible social change and abridge information accessibility inequities. Finding a way to bake an element that strives for social progress by applying the course work to communities outside of NKU into the course was the next step for O’Callaghan.

Clovernook Center For the Blind and Visually Impaired is a Cincinnati-based nonprofit. They’re the largest manufacturer of braille by volume in the world, responsible for producing braille translations of books for the Library of Congress and making braille menus for McDonalds.

When O’Callaghan learned about Clovernook, the opportunity to work together seemed serendipitous. Clovernook was looking to expand their reach to international regions to level shortages in accessible learning materials and wanted to collaborate with higher education institutions to develop learning materials.

Clovernook had recently minted a partnership with the African Storybook Initiative, an effort to publish multilingual storybooks to address a stark shortage of children’s books and improve childhood literacy in Africa. The initiative stores published stories in a database, spanning over 200 African-spoken languages.

These stories are authorized to be translated and published in braille thanks to the Marrakesh Treaty, an international agreement honored in many countries that waives copyright stipulations and allows text to be translated and published in braille without permission.

“What we’re trying to do with this initiative is help support the global community by making sure that young braille readers have more resources in the classroom, regardless of if they’re in the United States or if they’re in Rwanda,” said Samuel Foulkes, Clovernook director of braille production and accessible innovation.

Foulkes was working with the African Storybook Initiative, and having visited schools in East Africa to receive feedback from students and teachers on braille storybooks they had produced, he was advised that supplemental activities and lesson plans would greatly enhance the learning potential for these children.

This need was a glimmering gateway for O’Callaghan to get involved and solidified a mission for Build a Better Book as a course at NKU.

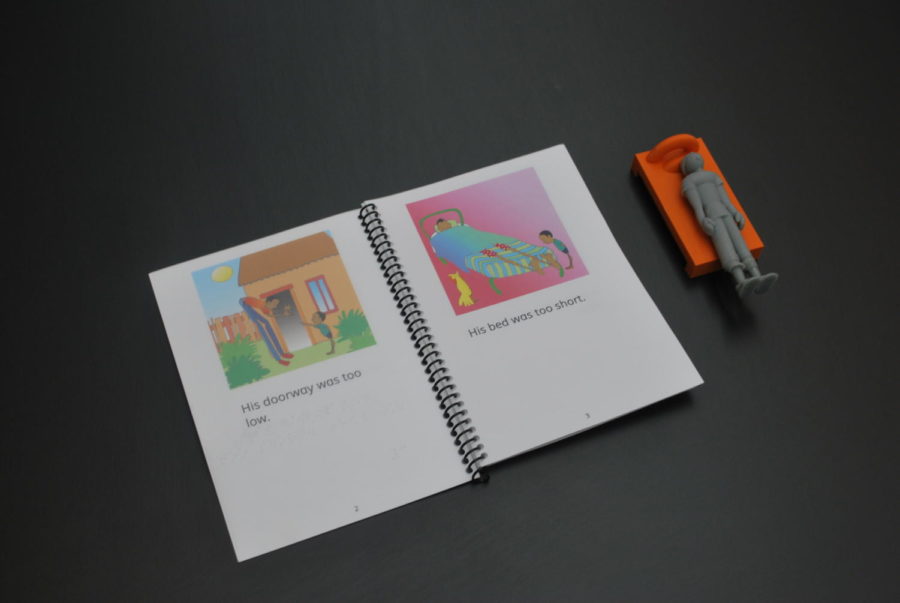

The course was piloted in the Honors College in Fall of 2022. Students worked in groups to select a storybook and ideate 3D models that would complement the reading experience through sense of touch. Students engaged with the stories to imagine the key stimuli in the stories—the objects that drive home meaning and create sensation beyond the literal message of the text.

One group developed tactile models for a story about a mother chicken deciding the safest place to lay her eggs.

“There were a lot of places where she thought she could lay her eggs, like a pool or a house and then a garden… then she last decided that the nest would be the safest place.” said Saumya Sharma, a student who took the class. “Our main goal was, if we were to make the children from Africa study the books, we needed them to have a real life experience.”

The process entails finding 3D print files on open-access platforms like Thingiverse or 3D scanning real-life objects, then modifying them as needed to make the user experience as straightforward as possible. Some models lack the realism to effectively convey how the objects truly exist. Others have flimsy design features or won’t stand upright. Students would find themselves reprinting objects that can take hours to finish to improve their functionality.

Over half of Clovernook’s team is composed of people that are blind or visually impaired, so these employees test the objects and offer testimony to their efficacy. Foulkes also keeps contact with a liaison for the project in Nairobi, Kenya, who collects feedback on the books and learning objects from students and teachers at partnered schools to guide development.

The types of consideration and problem-solving required to successfully create objects that meet standards for accessible learning is an opportunity for experience with technology that is untraditional for work in the humanities but becoming more applicable in a quickly advancing technological culture.

Build a Better Book is being taught in the English department this semester, and some students are capitalizing on a chance to write and publish their own children’s story to develop tactile models for.

But the vision for how to leverage 3D printing to promote learning and literary accessibility doesn’t halt at multimodal books. According to Foulkes, Clovernook is experimenting to develop an array of products, like dioramas, audio players and tactile book covers that could fortify learning for the blind and visually impaired in underserved areas across subjects, with a focus on how to shore up STEM education.

One product concept is a thin table-top board that snaps in place a puzzle with holes arranged in a checkered pattern that could be compatible with objects shaped like countries and labeled with braille, for instance. Children could arrange these pieces on the board by snapping them in place—almost like Legos—to study geography.

The outreach project in Africa is currently in its “resource and design collection mode,” as new stories are added to the database, design prototypes tested and STEM learning resources are considered. The learning tools that are developed and deemed to be viable will be presented in a catalog for African schools to choose what suits their needs, Foulkes said.

“We’re using these partnerships with a dozen or so schools over the next few years to really see what resources make an impact, and which resources specifically have an impact on learning goals,” Foulkes said.

Meanwhile, Clovernook is working to secure grants that would allow the partnered schools in Africa to be reimbursed completely for the books and objects.

Clovernook is delighted to have forged the partnership with NKU and is eager to establish new connections with universities to further the development and fabrication of multimodal learning materials, Foulkes said.

“We essentially get 20 young, interested minds to innovate and design the program,” Foulkes said.

The course exposes students to the forward-thinking and practical possibilities in reach at the Stego Studio while broadening perspectives on how to tackle global accessibility inequities.

“We kind of had to look at it in not a visual way because that’s not what it’s going to be used for,” said Jaycie Bussel, who took O’Callaghan’s Build a Better Book course in the Honors College. “It has definitely broadened my perspective, especially as an engineering student: how different people are going to use different products and how that’s going to be a different experience for each person.”

The course concept has turned heads of other academic professors too—a professor at State University of New York at Cortland has asked O’Callaghan to grant her the syllabus and is looking to launch the course and work with Clovernook remotely.

O’Callaghan has also been awarded a faculty project grant to purchase a 3D printer and other 3D printing equipment that is set to be at her disposal in May.

“It’s really hard for faculty that aren’t identified as disciplines that, yes, this is where you would have a 3D printer,” O’Callaghan said. “This is the big thing about makerspaces. It’s not just for the people that are like, ‘yeah, I know 3D printing. I need somewhere to 3D print… A lot of it is, ‘Hey, you’ve never 3D printed before. Why don’t you come and try it out?’”