Your donation will support the student journalists of Northern Kentucky University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

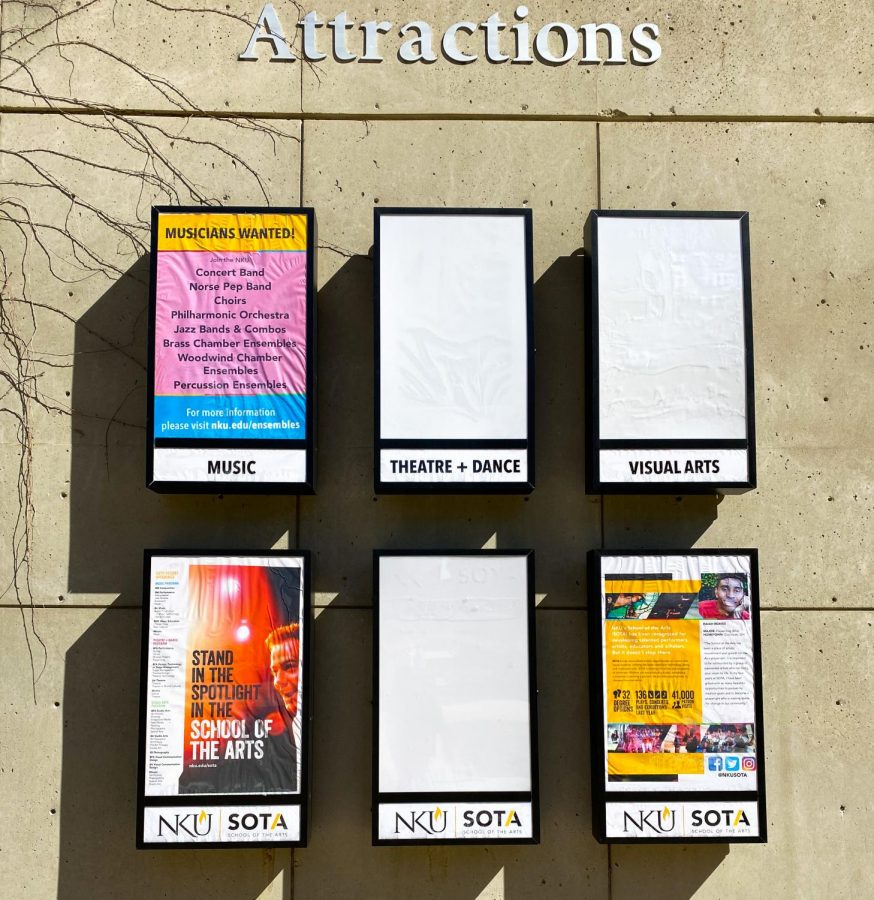

The Theatre and Dance “Attractions” board outside SOTA, which usually displays the semester’s upcoming events, is vacant.

‘It’s on us to keep it moving’: Theatre students imagine the industry post-pandemic

October 4, 2020

Editor’s note: Some of the ideas expressed in this story are opinions and predictions from theatre students. The intended purpose of this story is not to say what the future of theatre will or should look like but rather to predict what it might look like.

Theater is unique in that its livelihood relies entirely on delivering a live performance in front of a live audience. At least, it did up until March when COVID-19 wreaked financial havoc on the theatre industry. Fine and performing arts industries are estimated to lose 1.4 million jobs and $42.5 billion in sales due to the pandemic.

NKU’s School of the Arts (SOTA) canceled all live performances until Fall 2021, though some will be recorded and shown virtually this semester and next semester.

Broadway shut down in mid-March and won’t reopen until at least January 2021, making it the longest that the iconic theatre district has ever been closed.

Though the theatre industry is in an unprecedented and uncertain state right now, Trevor Browning, senior theatre BFA major, seems to think live theatre will eventually return to normal.

“I think it’s gonna take a long, long time. And when it does get back to normal, I think it might actually be for the better,” Browning said.

Before the pandemic, Browning was booked to work on one project after another through the end of this year. Though, that all changed over spring break, which was a “vacation that ended up lasting … months,” he said.

Blair Lamb, senior BFA musical theatre major, had plans of moving to a big city and pursuing a career in musical theatre.

“I’m a lot more hesitant to just pick up and make that move now, especially knowing that I might have a hard time getting a job once I get there,” Lamb said.

Isabel Sleczkowski, senior philosophy and technical theatre double major, was excited to jump straight into a prop designing career. Now she’s considering going to law school but doesn’t know if she can see herself practicing law for the rest of her life.

“Theatre, for me, is such a good creative outlet and it’s already been hard enough not doing it for these few months. I don’t know what I would do if I didn’t do it for years,” Sleczkowski said.

“I have a lot of colleagues … who were fired or who haven’t been getting income for months, and that’s not sustainable,” Sleczkowski said.

Massive, corporate-owned theatres might suffer some financial loss, but Lamb and Sleczkowski are more worried for small local venues.

“We’re watching smaller theatres really struggle with the loss of income and the complete pause that they’ve been forced to go into,” Sleczkowski said.

Despite the industry continuing to lose revenue, Browning, Lamb and Sleczkowski agree that theatres should not be hosting traditional performances right now.

“[Traditional live performances] are just not safe for the performers or the audience members,” Browning said.

Sleczkowski, who recently tested positive for COVID-19, thinks that practicing social distancing while working on shows is virtually impossible for cast and crew members. According to her, costume changes can involve as many as two or three people helping an actor change.

“A lot of people are jumping to get back to normal now, and I don’t think … that that is feasible and I think in the long run, it will actually end up hurting us,” Sleczkowski said.

The future of theater isn’t all doom and gloom, though. COVID-19 inadvertently has opened the door for unexplored creativity.

The Carnegie theatre performed “Godspell” through a Pyramid Hill Sculpture Park in Hamilton, Ohio. The park itself served as the set and actors walked across the park as the performance progressed. Audience members followed suit, and there were volunteers to make sure everyone maintained social distance.

During the height of quarantine, Lamb started giving piano and voice lessons through Zoom, which she said made her discover that she loves to teach. It pays just as much as her part-time job at a coffee shop, and her students range from 7 to 24-years-old.

Historically, live theatre has primarily relied on in-person auditions. An actor who lives in New York City or Chicago will have easier access to higher-profile auditions than an actor who lives in Cincinnati.

However, because of the pandemic, pre-recorded auditions that are sent off to casting directors are becoming more common. Lamb said this is a positive thing as it allows actors who don’t live in or can’t travel to theatre hotspots to have equal access and opportunity.

The pandemic also may lead to the industry reexamining its ethics (or lack thereof).

According to Sleczkowski, theatre is notorious for overworking cast and crew members.

“Especially for tech week, which is the week before a show opens, you’re usually working like 10 to 12 hour days, several days in a row. I don’t know [if] that’ll be something that we sustain in the future, and I think that’s a good thing,” she said.

Sleczkowski hopes that the industry will be more understanding and inclusive of people who are sick or differently abled.

The students were asked to describe how they feel about the future of theatre in one word:

“Hopeful,” Browning said.

“Hopeful,” Sleczkowski echoed.

“Resilient,” Lamb said.