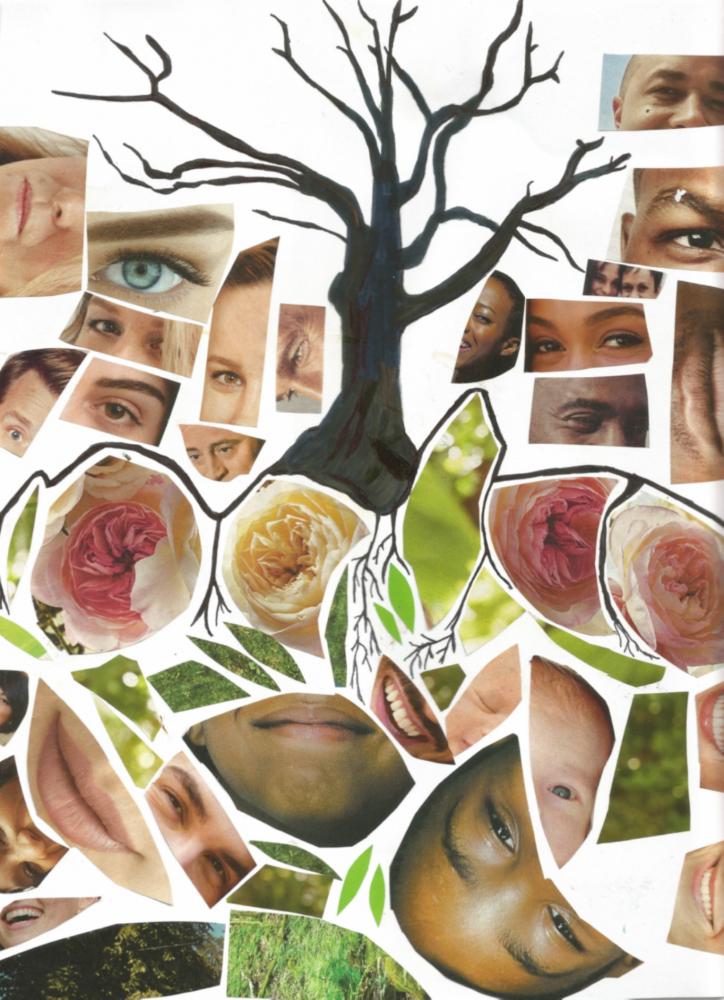

Illustration by Nicole Browning

REVIEW: Mourning the Creation of Racial Categories

A separation that has "eaten our family trees"

September 30, 2017

While many address the problematic racial divide in our society with discussion, action, and sometimes even apathy, Joan Ferrante took a different path: grief.

Her documentary, Mourning the Creation of Racial Categories, had an exclusive first screening in NKU’s University Center on Sept. 23.

Ferrante, professor of sociology at NKU, believes that before we as a society can effectively resolve or even come to a point of discussion about race, we must process the pain inflicted upon us by the societal institution of racial categorization.

The first historical example in the documentary that magnified this impact, and really the foundation of the film, was a story about two friends, Archie and Thomas. Although Archie appeared to be white, he was classified as black and thus a slave because his father was white and his mother was a black slave. In these times, racial categorization was maternal. Thomas, who appeared to be black, urged Archie to leave him, hoping that Archie could pass as white and escape to freedom.

“You can readily pass as a free man,” Thomas said to Archie in the documentary’s re-enactment. “It will be very easy for you to get away to those free states of which I’ve heard you speak so often. If I go with you, we shall be stopped and questioned…it is a great way to those free states and I’ve got little chance and no hope of ever getting there.”

With Thomas’ rugged, stained clothes and Archie’s clean-cut look and vest, the two men juxtaposed one another as Archie contemplated leaving Thomas to stay in slavery. The two men stood facing each other, but their lives were worlds apart. They embraced and separated, knowing that despite their same racial categorization, the colors of their skin would ultimately divide them.

It was 1996 when Joan Ferrante was first inspired to address the issue of racial categorization and its division of families. Many who would serve on the project in 2017 were not even born yet.

The team, students of the School of the Arts and Creative Writing program, assembled for a workshop held over winter break last year where the students responded to examples of the grief that comes with racial categories, especially the categories black and white. An intense study, the students not only had to thoroughly examine these historical accounts, but had to channel their own mourning into their creative products. The responses and artwork, ranged anywhere from a poem to a sculpture to a dance, are not only significant in representing that mourning, but incite mourning in their audience, as well.

Emanuel Picazo, a choreographer on the project, wanted to display the idea of “symbolic weight” everyone holds about race through a tangible object; the idea came to screen as dancers held scarves wrapped around their wrists.

The scarves, white in contrast to the dark skin and clothing of the dancers, grounded the audience as they processed the history of racism and bondage; the dancers struggled with one another, their faces crumpled. They faced each other, attempting to untangle their scarves. They realized their categories, their wrists literally tied up in whiteness.

A frantic song opened the number as the same doom-filled note blasted through the speakers repeatedly, bringing about a sense of urgency, a symbol for the initial trauma of racial categorization. As dancers of other races were slowly brought into the scene, they brought forth a symbol of human interconnectedness outside the bounds of socially constructed racial categories. The sound of a piano emerged, playing quickly but eloquently, almost as if rushing through hundreds of years of memories in a few seconds. Hanging on the last note before dropping its tempo, the song’s final tone conveyed a sorrowful and mournful mood, and slowed to provide room for the audience to mourn. Emanuel concluded the dance as performers of other races walked out of the scene, separated into their categories once again. This dance, the conclusion to the documentary, perfectly conveyed Ferrante’s message: we as a people were forced apart, and must process the grief before we can eventually come back together.

Kirsten Hurst, a creative writing student on the project, contributed a poem entitled, “That time I talked about race.” The poem, intended to be an examination of her own family tree, addresses the idea that society can’t see her “non-white classified” ancestors printed on her skin, and mourns the loss of family relationships through racial categorization in the process of creating her. A phrase she uses in the poem, “eaten my family tree,” transformed into a slogan for the project: Race ate my family tree.

Printed on the wristbands given out at the film’s showing, the phrase captures the essence of the project in one sentence. As the classifications based on our skin colors emerged, they separated our biological families and cut off our sense of humanity. This causes us to lose opportunities for relationships, growth and love in obedience to invisible lines drawn hundreds of years ago. As we ignore the wholeness of personhood and dissect our outer shells, we disintegrate our family lines in favor of the invisible ones, down to the roots of our family trees.