The trans-disciplinary approach: Science meets the humanities at NKU

May 12, 2017

Scrawling a web of circles on the chalkboard, Dr. KC Russell motioned for his students to move closer. Though the professor’s diagrams and frequent references to chemical compounds might have given any passers-by the impression of an organic chemistry lecture, it was apparent to anyone sitting cross-legged on the floor in room 116 of the Fine Arts Center that this was no ordinary science class.

Alongside Dr. Tracey Bonner, the Dance Coordinator within NKU’s theatre and dance program, Russell spent the Friday afternoon helping his team of undergraduate volunteers to choreograph a performance meant to help chemistry majors visualize concepts that may otherwise seem abstract.

“The big circles here represent Carbon atoms in organic chemistry terms. My visualization is that each of these will represent a person,” Russell said.

The class arranged itself into clusters, each small group of students making its own attempt at imitating the figure scrawled in chalk. A student’s right hand linked with her adjacent partner’s wrist, she extended her left arm and left leg as the third member swooped in to grab them, simulating the attraction between three atoms in a molecule.

Bonner coached each dancer through their routine, making sure that the connections between them were visible from all angles.

It is this sort of collaboration between unexpected fields that reveals the “transdisciplinary” approach to learning and instruction that Dr. Diana McGill, Dean of NKU’s College of Arts and Sciences, sees as essential to a holistic education.

“I think that any major benefits broadly from this Arts and Sciences background,” McGill said. “I think that certainly, STEM disciplines can learn how to approach rhetorical communication from English majors. I think that when a sociology major takes a physics class, they learn this whole new way of thinking about that world that could influence their philosophy.”

Cooperation among different fields of study provide more than just benefits to the individual student, according to McGill.

“In a transdisciplinary approach to education, you can attack a big problem,” McGill said. “If you’re trying to solve a problem like hunger in a region, as a scientist myself, I can see the scientific side of it that may help, but someone who does ecology of urban planning in the biology department would have different ways of looking at it, and then communications specialists or historians might have their own way.”

In the Fine Arts building, Bonner and Russell are solving a problem of their own: presenting scientific concepts that take place on a microscopic level in a way that students can more tangibly grasp.

“One thing that we really want to do is be able to have these kinesthetic diagrams,” Bonner said. “Different people learn in different ways: some people learn orally; some people learn visually; and some people learn kinesthetically — by moving. I think this could be a valuable tool for people who learn from the kinesthetic perspective. It lets them see a concept in action, not just in animation.”

While Russell plans to use videos of the completed dance as a visual aid for his organic chemistry classes, Bonner also sees educational value for those involved with the project.

“Hopefully for the dancers, it helps them build more interest and want to do more work in the sciences,” Bonner said. “We have about 25 majors in dance, but only one who majors in both worlds. That one person made this all happen.”

That one person was Kiersten Edwards.

In the 2015-2016 Fall semester, prompted by an assignment in Russell’s Chemical Information and Writing course, Edwards submitted a proposal that suggested setting concepts in organic chemistry to dance.

“The project came naturally to me,” Edwards said. “I always knew I was able to learn dances quicker than chemistry and I was able to visualize electron movement as movement of the human body easier than I could by just looking at a paper.”

Edwards’ proposal piqued the interest of Russell and Bonner enough for the two professors to begin plans to bring the idea to fruition.

“I said, ‘wow, that’s really cool, do you mind if I borrow that idea so I could write a proposal to get funding?’ and so I reached out,” Russell said. “We’ve been planning this for a little over a year now. It was over the summer that the idea kind of percolated.”

The three collaborators were able to receive financial backing from NKU’s UR-STEM program, a paid study opportunity that is available to undergraduates who have yet to participate in a funded research experience.

“This is a great example of how you can use both parts of the brain,” Bonner said. “Science and art are both qualities that make people human.”

McGill sees this sort of marriage of fields, both of which reside in her College of Arts and Sciences, as a prime example of Liberal Arts education in action.

“Classes that are naturally pulling in students from all disciplines, where students can talk about their interests are what students can grow from,” she said.

McGill also suggested making an effort to forge more of these connections among Humanities majors.

“What if we had humanities meetings once a month,” McGill offered, “where there were writing sessions where all of the people who were interested got together, presented their works and writing, and they evaluate it? STEM disciplines are already holding regular meetings where they get together and talk about pedagogy, and how we increase success rates in these difficult courses.”

For some, like Dr. Tamara O’Callaghan, an NKU English professor, transdisciplinary learning is entrenched in their field of study.

“I trained in graduate school in the digital humanities,” O’Callaghan said. “At that time it was called ‘Humanities computing,’ but the name has changed. This is the idea of looking at the way that technology and particularly hard technology in terms of computer science techniques can be used in Humanities studies.”

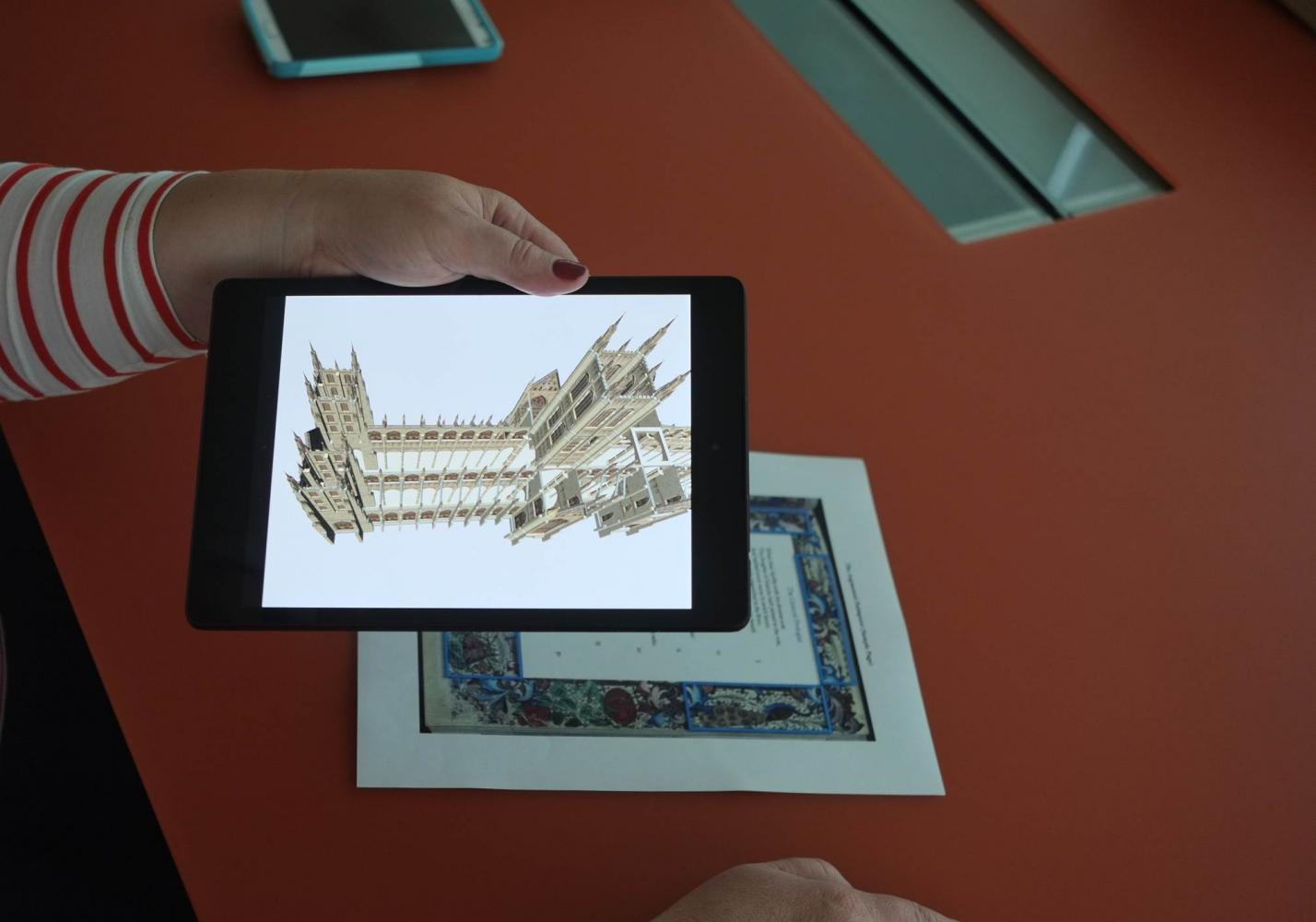

Alongside Andrea R Harbin, a fellow English professor and digital humanist from the State University of New York, O’Callaghan is currently working on developing a virtual teaching tool called The Augmented Palimpsest. Conceptually similar to Pokemon Go and Google Glass, the project seeks to let iPhone, iPad and Android users immersively interact with Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales.

Users will be able to hold their device over a printed page of the manuscript, bordered with the original artwork that originally accompanied the text. A dot matrix similar to QR code is hidden beneath the intricate designs, which allows for the art to spring to three-dimensional life on the phone screen. Students can then tap on highlighted sections of the page for extra analysis and context.

“As of now, we’ve created a prototype and a 3-D model of Canterbury Cathedral where the room can come off, and you can go inside,” O’Callaghan said.

Though one might associate augmented reality and virtual reality with computer science, O’Callaghan finds that non-STEM fields play a vital role in their development.

“They’re starting to come into the public focus more through museum studies and history,” O’Callaghan said, “because of the idea of rendering artifacts that people could see as a 3-D object when they can’t actually travel to go see it.”

She also noted that augmented reality is growing more popular in the realm of medicine, where cadavers and resources are in short supply.

“In terms of reading, though, there’s a certain texture and heft to holding a physical book and turning the pages that connect the synapses in your brain differently than texting with your thumb on a smart device,” Callaghan said. “Does that mean that the processes of texting with your thumb or reading on a phone are bad? We’re not going to know until a neuroscientist studies it. But to me, they’re probably isn’t going to be much difference. It’s like going from handwritten manuscripts to books. There must have been a change then, but we didn’t have a neuroscientist there to observe them.”

These changes in learning, set in motion by innovations in technology, are what O’Callaghan finds most exciting about teaching in the digital age.

“The humanities and sciences work together,” O’Callaghan said. “Especially in the Digital Humanities. You need technological proficiency, but you can’t do it without being well-trained in a traditional Humanities discipline. It gives us ways of making sure our students graduate with the sort of technical skills that are relevant in the 21st century.”

The field’s value can be made manifest in unexpected ways.

“I know someone whose spouse got a Ph.D. in computational linguistics,” O’Callaghan said, “and couldn’t get and academic job, but then got a great job in California for Mattel teaching Barbie how to talk. So, there are actual things you can do outside of academia with it.”

Chemistry, dance and English all residing within her College of Arts and Sciences, McGill recognized that the diversity of fields she oversees greatly benefits its students, more easily facilitating projects that cross disciplinary divides.

“These connections would never happen if there was a science college over here and a humanities college over there,” McGill said. “Well, not that it wouldn’t happen but it would be harder for it to happen if they were separated. So I think that – although I don’t know the history of how they formed – there’s a lot of benefit to the students in a college that broad.”