Explaining contract cheating and how NKU is fighting it

Catching academic dishonesty has become increasingly confounding since the emergence of open-access AI chatbots. Here's how some educators and entrepreneurs are encouraging honesty.

April 6, 2023

For many students in the last half decade, coping with the chaos of college has meant finding ways to get assignments done without actually doing them. This is called contract cheating, and it has become a formidable multimillion dollar business.

The rise of accessible Artificial Intelligence (AI) chatbots, like ChatGPT, equips students to obtain work to submit for classes without a human intermediary. AI chatbot outputs are spotty, sometimes churning out irrelevant or false information.

As student access to modes of academic dishonesty abounds with increasing—but far from unfaltering—sophistication, education institutions and instructors are scrambling to create policy and preventative measures in response. Some of these tools are being designed and tested in our own backyard.

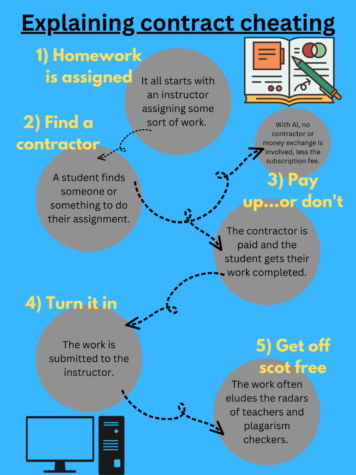

Contract cheating is the act of outsourcing school assignments to a third party. This can be through a peer, a website or social media, and it is usually in exchange for a fee. Countless online hubs—sometimes called essay mills—offer students in a variety of majors and levels work for purchase, whether it be solutions to homework problems or entire essays, while allowing students to paste their name on them and avoid being flagged for plagiarism.

That’s when the third-party involved is a human. Turning in work that was generated by AI is still defined as contract cheating, because original work is being outsourced and mislabeled as done by the student.

The practice is frowned upon in academia because its affordability and expedience encourages students to opt out of engaging with class content.

Contract cheating and ghostwriting have existed for centuries in different capacities. Think about ghostwriting of music lyrics or casually enlisting an acquaintance to do an assignment in exchange for pocket change. But the internet has lubricated the process and proliferated its popularity with the advent of freelance sites like Chegg, Course Hero and Fiverr where students can digitally connect with people who do homework for compensation—and now, AI.

How is artificial intelligence affecting contract cheating?

The reasons why paid contract cheating and AI-enabled contract cheating are attractive to students are the same: both are difficult to detect for plagiarism.

“The teacher doesn’t have the ability to see that it’s been copied from something they don’t have. It also may not be detected by systems like TurnItIn, because assuming the person you’re paying is producing a new work product for you, then it won’t match anything,” Dr. James Walden, a computer science professor, said. “That’s a pretty big assumption though.”

It’s common for assignment contractors to receive requests for similar assignments, resulting in templates and standardized work that may get flagged for unoriginality. On the other hand, each output by an AI Chatbot is singular, decreasing its visibility by instructors and tools looking for cheating.

AI chatbots are hampering some essay mills, with some contractors who make a living off the trade reporting a fall in business.

How is contract cheating detected and punished?

Software like TurnItIn is used in academic settings to flag plagiarism. It compares linguistic patterns against a repository of other works and checks for correct citations, determining with varying levels of accuracy if a paper contains plagiarized information. Contract cheating—and now AI-generated work—usually goes unflagged, however, because the work is original despite not being done by the student.

A new tool called Auth+, designed by the Northern Kentucky based education-technology startup Sikanai, verifies student authorship with a different approach. The software plugs into learning platforms, like Canvas and BlackBoard, and asks the student a series of AI-generated questions that test their familiarity with the writing.

“We ask you questions about your writing style, your contents, what was in it, and then your memory of what you wrote,” Barry Burkette, co-founder and executive director of Sikanai, said. “We’re asking questions more about you—the choices you make when writing, and then from those answers, giving the instructor a score of how familiar you are with it.”

Auth+ is being piloted at NKU in the Haile College of Business and other universities, such as Georgetown College, Pakistan at the Institute for Business Accreditation and the University of Manitoba. The software has seen favorable reviews so far, Burkette said.

The technology only tests for familiarity with written work as of now, but as research, development and funding add up, Burkette hopes to expand the technology to test for familiarity with works in other areas of study, like computer sciences and non-English languages.

Burkette said that the Auth+ model for preventing cheating upholds academic integrity and holds students accountable for the work they turn in without being invasive or stirring mistrust. Programs like TurnItIn and LockDown Browser that access and analyze student data, he argues, are a violation of student-teacher trust.

Instructors differ on the ethics of software that tries to detect plagiarism and contract cheating. Dr. John Alberti, chair of the English Department, said many English faculty agree that checking student writing with tools like TurnItIn is a breach of trust.

“It automatically puts every student under suspicion,” Alberti said.

A tool like Auth+, Alberti argues, still crosses the boundary of student and instructor trust, despite the absence of data collection.

“It’s still a policing measure,” Alberti said.

A common practice in English studies to encourage academic integrity and avoid using such tools is to design writing assignments in a manner that emphasizes the revisional process of writing, like multiple drafts and workshopping activities, according to Alberti.

But in foundational courses, particularly in a student’s specific area of study, ensuring students learn the basics is integral to their competency as they advance through college programs and into the workforce. Walden said he fears that designing assignments that deter cheating in introductory computer coding classes will be tough, because AI chatbots are very capable of producing accurate basic code. Front-end cheating detection tools may be a necessary part of the submission process if it means students can’t skip out on the learning, said Walden.

At times, discerning students who are abusing contract cheating can be obvious, said Walden. Student work that is inconsistent with the quality that they usually turn in is a tell-tale sign.

When this occurs, Walden said he investigates popular contract cheating sites like Chegg and Freelancer for his assignments. Since many contract cheating sites maintain the semblance of legitimate academic resources, cheating investigation features are usually baked in, Walden said. If he finds his assignments in their databases, he can follow transaction records to see if any students bought solutions to the assignment.

But AI chatbots present a new set of problems for detecting contract cheating cases. One solution being pursued with haste is the use of subtle watermarks to identify work generated by specific chatbot clouds, Walden said.

Regardless of how the contract cheating was carried out, asking a suspected student to explain their thought processes to arrive at their solution can usually verify if they understand the work.

“Ask them to explain the assignment, and especially with the ones where they get the really professional results. They’re not going to be explaining the code that they were given,” Walden said. “With code it’s often very obvious—quickly—that they can’t explain their solution.”

And with AI tools gradually creeping into the educational and professional norm, policies on an institutional and classroom level will likely make headway to delineate appropriate and inappropriate uses for them.