Student-created chemical recycling machine could cut costs, benefit the environment

November 2, 2014

Tucked away in the corner of a small research lab on the second floor of the science center is a funny-looking, gurgling machine.

Constructed from what looks like the remnants of a pool noodle, your grandmother’s crock pot and clear tubing you’ve seen at your local hospital, the machine recycles used chemicals—separating concoctions such as those served up from students performing experiments in labs across campus.

But don’t be fooled by the machine’s looks. It is merely a prototype for a future model that could one day help save the environment—both here at NKU and beyond.

Image #1 Image #2 Image #3

Image #1: The end of the machine that the chemical mixture is placed into to be

"recycled" into separate, pure forms.

Image #2: Glass containers at the other end of the machine store the distilled,

pure chemicals.

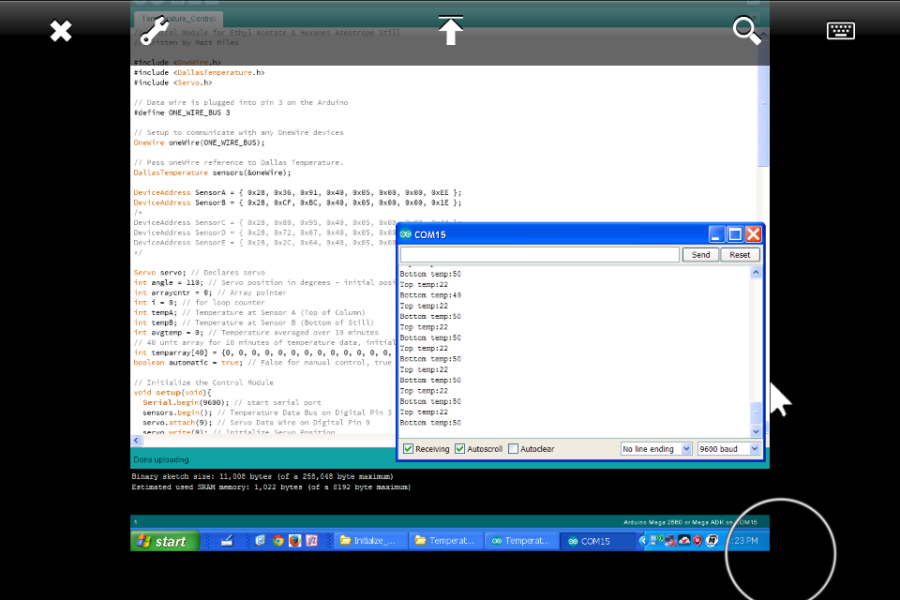

Image #3: A view of the computer programming device used to run the machine.

The mean, green, chemical recycling machine

Matthew Miles, a 2014 NKU graduate, created the machine. He said there was already a plan for recycling chemicals used in the labs on campus when he started doing research in an NKU chemistry lab last year as a biochemistry major. However, he said the current plan only covered part of the necessary work.

“You would have this mixture, ethyl acetates and hexanes were the most common, and there really wasn’t anyway you could separate those,” he said. “All you could really use [that solution] for was for cleaning glassware or for chromatography.”

However, Miles changed that with this machine.

He started on the project to do more than just take off the liquid from the solids left in waste. His machine separates the different liquids present in the leftover solution with high rates of purity—allowing them to be reused again and again.

“These are just standard laboratory solvents used in our labs,” NKU Chemistry professor KC Russell said. “After we do whatever reaction or process, we are left with the remnants of those chemicals that either have to be disposed of or recycled in some way… the green thing is to try and reuse them. But we can’t reuse them without processing them in some way. So this is one way to get them into pure form, so they are reusable.”

The key thing about this procedure, according to Russell, is that the leftover solution is still a mixture of two different components.

“What Matt [Miles] did was look through the chemical literature to see if there were ways to get these two components separate from each other so they both could be used in pure form,” he said. “That’s kind of where he has blossomed in this area.”

The machine works through distillation, the purification of a liquid by a process of heating and cooling. Miles said it is kind of like taking the coffee beans out of your cup of coffee.

“So say you just made coffee, you gotta run water through the coffee to get it there. Then at the end let’s say you’re done with the coffee and you want to get the water back,” he said. “This is basically a coffee unmaker.”

The machine usually takes about a day to complete the distillation process.

To the best of Russell’s knowledge, no one has made a single instrument that does all of this, and he said the mechanized process could be generalized to apply to the distillation of most solutions.

According to Miles, the chemistry department has already ordered the parts for a larger scale model, “so the construction of that is underway.”

Miles said he has also been meeting with business leaders from across the country to secure funding to take his machine to the next level.

Cutting costs

It’s not that the original mixture of liquids left over from the solid—the remnants of the older means of recycling— isn’t useful to the departments, but they can use the now-accessible pure substances for more things.

“It takes waste that’s been building up and makes it so that the university doesn’t have to buy new solvent and doesn’t have to truck it off to waste,” Miles said. “These materials are not cheap; ethyl acetate is about $70 to $80 a bottle.”

Jeff Baker, NKU’s environmental safety coordinator, likes the idea of this recycling—both for its financial savings and its environmental benefits.

“This recycling allows us to save money on both sides. Not having to buy more of the reused materials obviously saves us money upfront, but then there is not having to pay to have more of that material taken out. It helps the environment too.”

Baker said the 55-gallon drums (that a lot of the chemical waste is stored in) cost about $250-350 dollars each to have taken away. He added that NKU racks up around $25,000 a year in chemical waste costs alone.

Before the waste is taken off campus, it sits in a large storage facility called “the cave” on the first floor on the science center, according to Baker. NKU is allowed to store these materials on campus for specific periods of times and then they must be taken away. This happens usually about once per semester by an outside company.

Most chemicals are stored on campus in four liter bottles. Some are separated down further and hauled off, while others are treated on a case-by-case basis.

Path to a greener NKU

Most of the chemicals that are disposed of are incinerated in extremely hot fires after they are taken off campus, where several hundred gallons are reduced to ashes (and subsequent gasses), according to Baker. Some of those ashes are then hauled off to landfills depending upon what they are.

The materials in the particular liquid solutions that Miles’ new machine can recycle for reuse are composed of carbon and hydrogen, Russell said. So, the ability to save these chemicals for reuse saves them from eventually being burned into a mixture of gasses that would be comparable to that of “burning wood,” according to Russell. While that doesn’t sound so bad for the atmosphere (minus the added carbon dioxide), the problem with the chemicals’ would-be environmental impact is that the chemicals contain impurities, which would cause more severe harm to the environment if burned.

Regardless, Baker said all of these processes, both the recycling and the disposal, remain EPA approved and meet all of the required standards.

However, he said the key for this recycling process to work is for people to not call the recyclable solution ‘waste.’

“It must be labeled as recyclable material for it to be distilled and reused,” Baker said. “Once we call it waste, it must, according to standards, be taken out.”

Overall Russell said the creation of this machine and its process are important for the future of recycling chemicals.

“It would apply to a lot of things,” he said. “But you can’t just say this will eliminate all chemical waste because that it will not do. But it can certainly recycle large volumes of solvents.”